Perseverance: Some Early Navcam (navigation Camera) Images Taken Over The (Earth) Weekend On Sol 2. Originals

Perseverance: Some early Navcam (navigation camera) images taken over the (Earth) weekend on sol 2. Originals are here: [1] [2] [3] [4]. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

More Posts from Sergioballester-blog and Others

ALL 👏🏾 OF 👏🏾 THEM 👏🏾

Amazing Space Shuttle Shot. 🚀

After completing its SSO-A mission of launching a record breaking 64 satellites at once, the B5 Falcon 9 booster landed for the third time breaking another record!

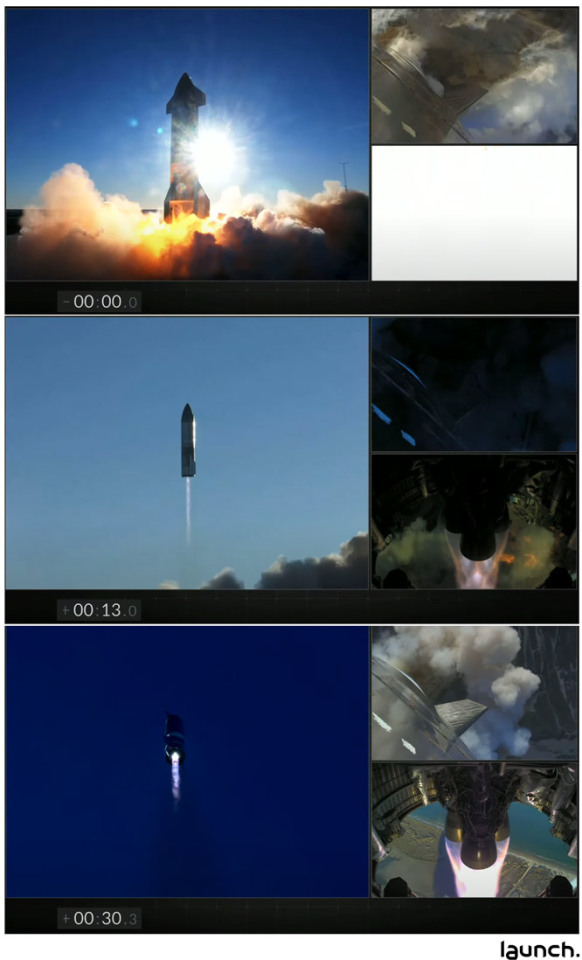

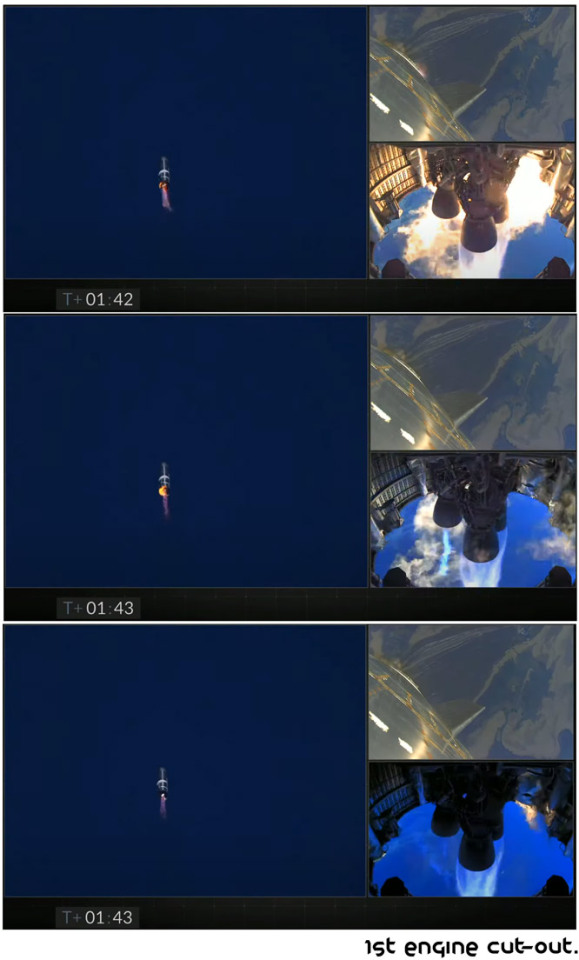

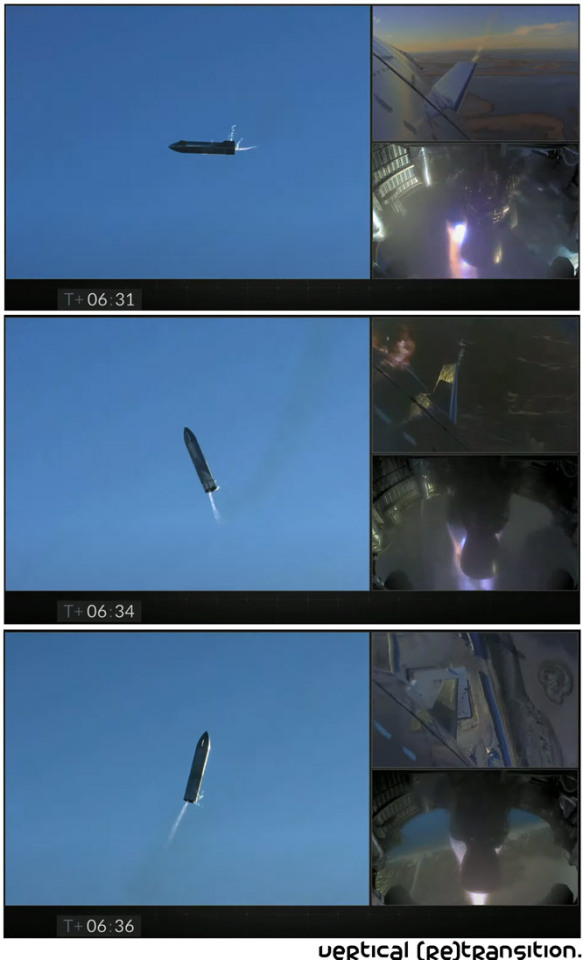

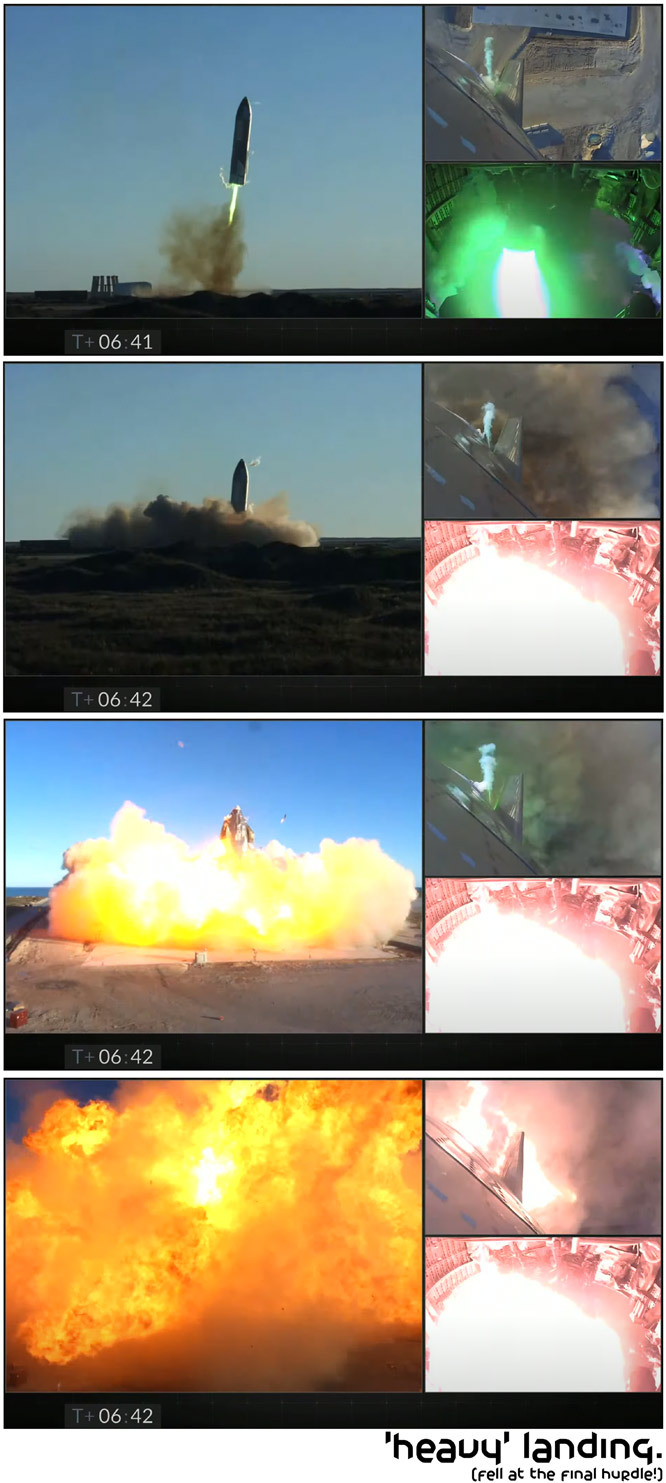

The historic - and, rather eventful - test flight of the SpaceX SN8 prototype. In spite of its heavy landing and subsequent destruction of the craft, I think in most other respects, it was a resounding success.

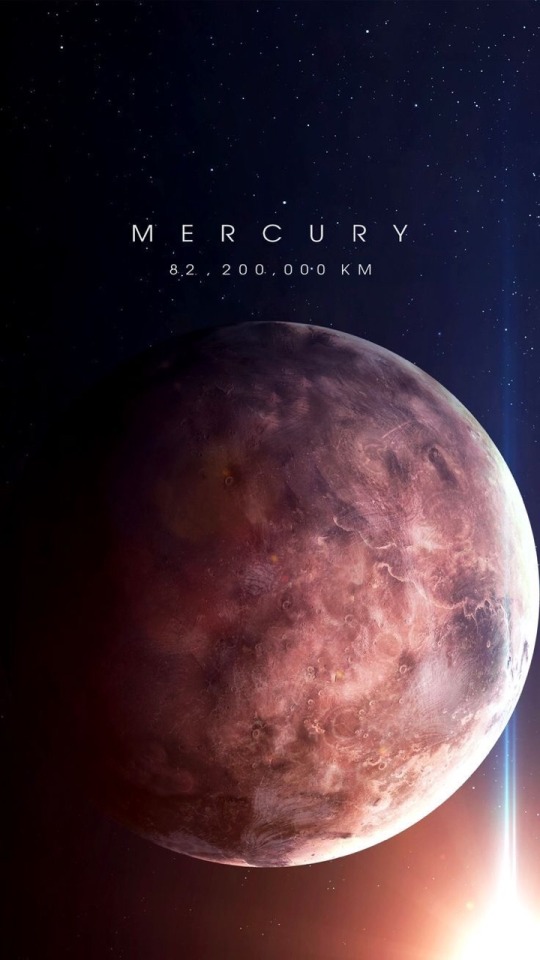

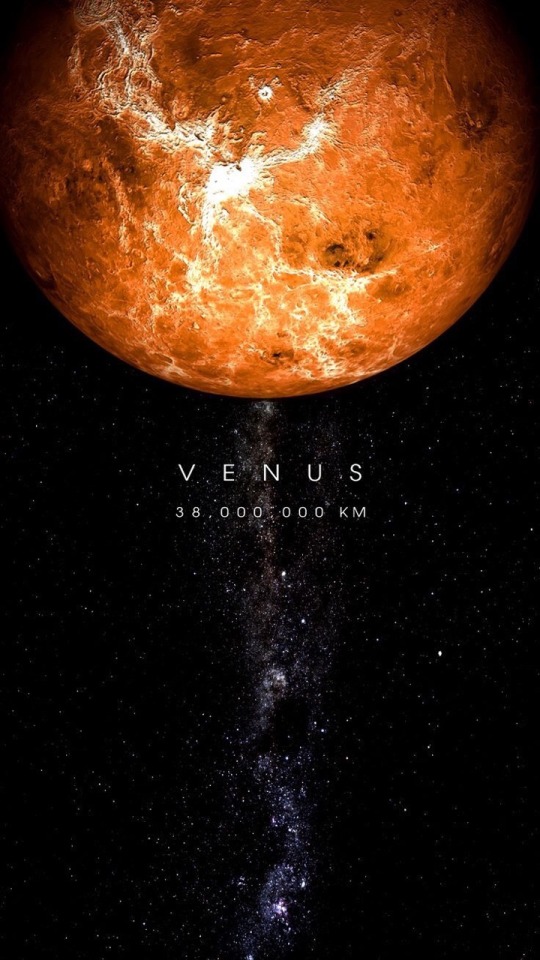

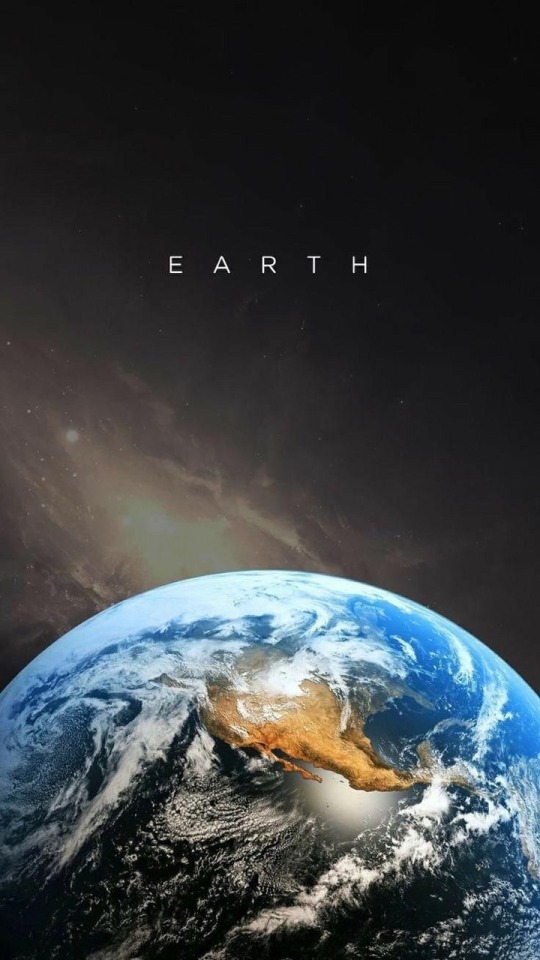

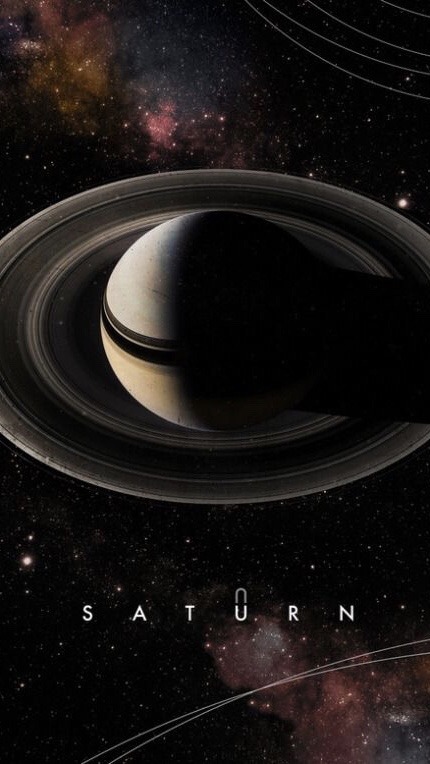

Solar System

•please like or reblog if you use

Sampling the ocean on Enceladus by europeanspaceagency

One Step Closer to the Moon with the Artemis Program! 🌙

The past couple of weeks have been packed with milestones for our Artemis program — the program that will land the first woman and the next man on the Moon!

Artemis I will be an integrated, uncrewed test of the Orion spacecraft and Space Launch System (SLS) rocket before we send crewed flights to the Moon.

On March 2, 2021, we completed stacking the twin SLS solid rocket boosters for the Artemis I mission. Over several weeks, workers with NASA's Exploration Ground Systems used one of five massive cranes to place 10 booster segments and nose assemblies on the mobile launcher inside the Vehicle Assembly Building at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida.

On March 18, 2021, we completed our Green Run hot fire test for the SLS core stage at Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. The core stage includes the flight computers, four RS-25 engines, and enormous propellant tanks that hold more than 700,000 gallons of super cold propellant. The test successfully ignited the core stage and produced 1.6 million pounds of thrust. The next time the core stage lights up will be when Artemis I launches on its mission to the Moon!

In coming days, engineers will examine the data and determine if the stage is ready to be refurbished, prepared for shipment, and delivered to KSC where it will be integrated with the twin solid rocket boosters and the other rocket elements.

We are a couple steps closer to landing boots on the Moon!

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

The first palaeontologist on Mars

(Image: Artist’s impression of NASA’s Perseverance rover on Mars)

Today NASA’s Perseverance rover landed on Mars. I don’t usually talk astronomy on this blog, but this time it’s relevant because—as you might have read—Perseverance is more or less the first palaeontologist on Mars!

Let me explain.

(Image: Satellite topography map of Jezero Crater, the site where Perseverance landed)

The site where Perseverance is landing, Jezero Crater, is a meteor impact crater near Mars’s Equator (say that 10 times fast!). It has evidence of a delta—the geomorphic feature that occurs when running water enters a large body of water. Orbital analyses also suggest it’s filled with carbonate rock—the kind that tend to deposit at the bottom of bodies of water.

Jezero Crater is not filled with water today. But the evidence strongly suggests it once was. If we’re going to find evidence of life on Mars, this is a good place to start looking.

Microbial fossils

When you think of fossils, most people think of giant T. rex skeletons, or frozen woolly mammoths, or neanderthal skulls. Maybe you’ve been around the block a bit, and you think about corals, or plant fossils, or tiny fossil shells. But some of the most common and important fossils on Earth are even tinier. Microbial fossils are commonly made by bacteria, archaea, and the like.

(Image: A cross-section of a stromatolite fossil, showing the multiple layers)

Some of the earliest fossils on earth are called stromatolites. They occur when bacterial colonies grow together in a mat—then, over time, sediment deposits over the colony, and the bacteria form another layer on top of the previous layer. Over time, many layers can be formed.

(Image: Helium Ion Microscopy image of iron oxide filaments formed by bacteria)

Although we breathe in oxygen and breathe out carbon dioxide, many microbes are not quite so restricted, and can breathe anything from sulphur to iron to methane or ammonia. When they do this, they often leave behind solid waste products, such as the above iron oxide filaments, that give away their presence. We can tell these apart from normal minerals in a number of ways, including by the relative proportions of different isotopes in them.

(Image: Schematic digram showing how molecular fossils form and are studied)

However, some of the most important fossils are molecular fossils. Living organisms produce a variety of different organic molecules; even long after the bodies of these organisms decay, those molecules can stay behind in an altered form for millions or even billions of years. If we’re looking for evidence of life on Mars, this might be our best bet.

Enter Perseverance

(Image: Diagram of Perseverance rover showing different instruments)

The Perseverance rover is overall similar in design to the Curiosity rover that landed in 2012, but there are some key differences—and most relevant here is that it’s a geological powerhouse. It’s got a number of instruments designed to carry out detailed geologic investigations:

RIMFAX is a ground-penetrating Radar unit. Like normal Radar, it works by sending radio waves into the ground; different materials affect the radio waves differently, as do transitions between different materials. This will allow us to, for the first time, study the geology of Mars below the surface to get an idea of what has been going on down there.

(Image: This is the kind of result produced by ground-penetrating radar—a rough image of the stratigraphy below the surface.)

PIXL (Planetary Instrument for X-ray Lithochemistry) shoots x-rays at samples and examines how they fluoresce in reaction. This allows for the detection of the elemental composition of a sample—helping us better understand the geology of the area, and potentially detect signatures of life.

SuperCam is a multi-function laser spectrometer that uses four different spectroscopy methods to examine the composition of samples. They all work in similar ways—essentially, different molecules react to laser stimulation differently, and different amounts of energy are required to make different molecules vibrate. The way that these molecules react can help us identify their composition, and the hope is that this may allow us to detect molecular fossils (these methods allow us to detect molecular fossils on Earth!)

SHERLOC (Scanning Habitable Environments with Raman & Luminescence for Organics & Chemicals) is another spectroscopic instrument—this one, however, is more precise, and optimised for detecting trace biosignatures in samples. It works similar to the above, using an ultraviolet laser to scan a 7 × 7 mm zone for evidence of organic compounds.

In addition to studying samples in situ, Perseverance will package small samples and leave them behind on Mars. A planned future mission will collect these packaged samples and launch them into space, where an orbiter will collect them and—hopefully—return them to Earth. This would be the first time that samples have ever been recovered from Mars, and would go a long way in increasing our understanding of the Martian environment and geology.

There’s no way of knowing yet what Perseverance will find—but even the fact that a robot palaeontologist is on Mars is incredibly exciting. Here’s to many years of discovery!

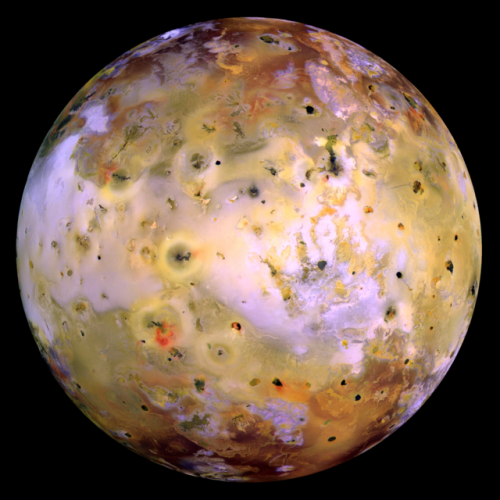

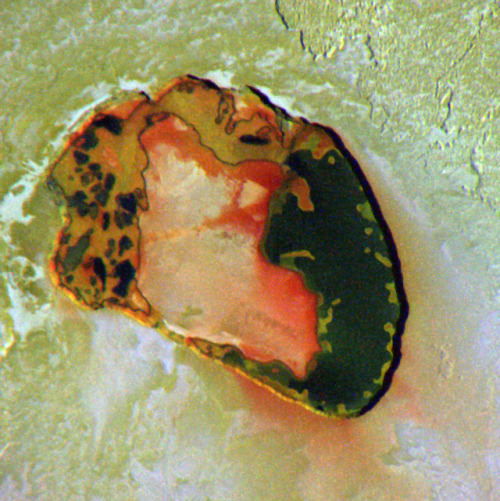

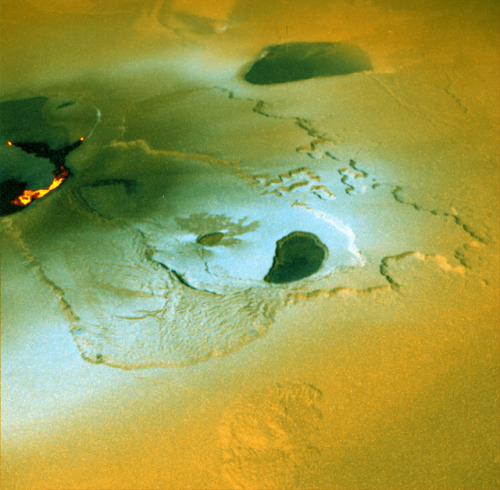

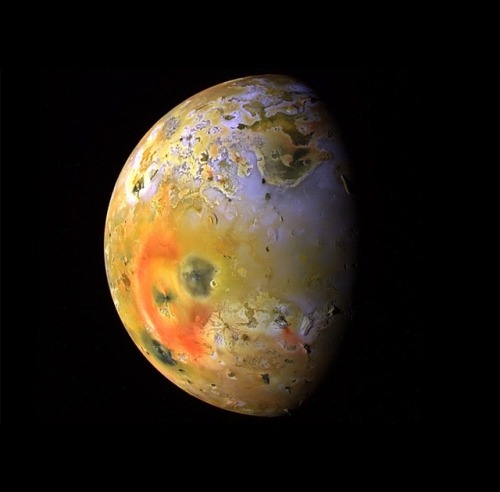

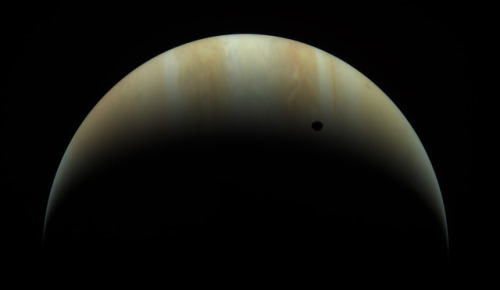

Io - The Volcanic Moon

Looking like a giant pizza covered with melted cheese and splotches of tomato and ripe olives, Io is the most volcanically active body in the solar system. Volcanic plumes rise 300 km (190 miles) above the surface, with material spewing out at nearly half the required escape velocity.

A bit larger than Earth’s Moon, Io is the third largest of Jupiter’s moons, and the fifth one in distance from the planet.

Although Io always points the same side toward Jupiter in its orbit around the giant planet, the large moons Europa and Ganymede perturb Io’s orbit into an irregularly elliptical one. Thus, in its widely varying distances from Jupiter, Io is subjected to tremendous tidal forces. These forces cause Io’s surface to bulge up and down (or in and out) by as much as 100 m (330 feet)! Compare these tides on Io’s solid surface to the tides on Earth’s oceans. On Earth, in the place where tides are highest, the difference between low and high tides is only 18 m (60 feet), and this is for water, not solid ground!

This tidal pumping generates a tremendous amount of heat within Io, keeping much of its subsurface crust in liquid form seeking any available escape route to the surface to relieve the pressure. Thus, the surface of Io is constantly renewing itself, filling in any impact craters with molten lava lakes and spreading smooth new floodplains of liquid rock. The composition of this material is not yet entirely clear, but theories suggest that it is largely molten sulfur and its compounds (which would account for the varigated coloring) or silicate rock (which would better account for the apparent temperatures, which may be too hot to be sulfur). Sulfur dioxide is the primary constituent of a thin atmosphere on Io. It has no water to speak of, unlike the other, colder Galilean moons. Data from the Galileo spacecraft indicates that an iron core may form Io’s center, thus giving Io its own magnetic field.

Io was discovered on 8 January 1610 by Galileo Galilei. The discovery, along with three other Jovian moons, was the first time a moon was discovered orbiting a planet other than Earth.

Eruption of the Tvashtar volcano on Jupiter’s moon Io, photographed by New Horizons.

Image credit: NASA/JPL/Galileo/New Horizons ( Stuart Rankin, Kevin Gill)

Source: NASA

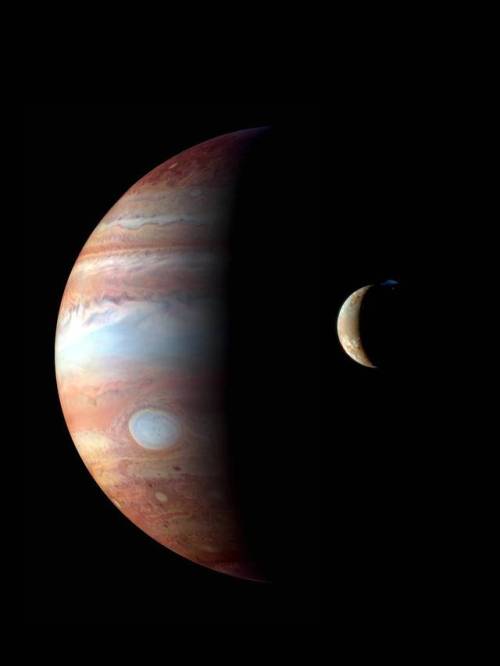

Celebrating Five Years at Jupiter!

We just released new eye-catching posters and backgrounds to celebrate the five-year anniversary of Juno’s orbit insertion at Jupiter in psychedelic style.

On July 4, 2016, our Juno spacecraft arrived at Jupiter on a mission to peer through the gas giant planet’s dense clouds and answer questions about the origins of our solar system. Since its arrival, Juno has provided scientists a treasure trove of data about the planet’s origins, interior structures, atmosphere, and magnetosphere.

Juno is the first mission to observe Jupiter’s deep atmosphere and interior, and will continue to delight with dazzling views of the planet’s colorful clouds and Galilean moons. As it circles Jupiter, Juno provides critical knowledge for understanding the formation of our own solar system, the Jovian system, and the role giant planets play in putting together planetary systems elsewhere.

Get the posters and backgrounds here!

For more on our Juno mission at Jupiter, follow NASA Solar System on Twitter and Facebook.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

-

caporalepapillon liked this · 4 years ago

caporalepapillon liked this · 4 years ago -

pheasant--plucker reblogged this · 4 years ago

pheasant--plucker reblogged this · 4 years ago -

sigma-umbra reblogged this · 4 years ago

sigma-umbra reblogged this · 4 years ago -

sigma-umbra liked this · 4 years ago

sigma-umbra liked this · 4 years ago -

cynthiafp liked this · 4 years ago

cynthiafp liked this · 4 years ago -

afragmentcastadrift reblogged this · 4 years ago

afragmentcastadrift reblogged this · 4 years ago -

secretplanstofightinflation reblogged this · 4 years ago

secretplanstofightinflation reblogged this · 4 years ago -

jimizarrocker liked this · 4 years ago

jimizarrocker liked this · 4 years ago -

jbatispte reblogged this · 4 years ago

jbatispte reblogged this · 4 years ago -

jbatispte liked this · 4 years ago

jbatispte liked this · 4 years ago -

samantha---h liked this · 4 years ago

samantha---h liked this · 4 years ago -

new-great-age-of-discovery reblogged this · 4 years ago

new-great-age-of-discovery reblogged this · 4 years ago -

mdavis1506 liked this · 4 years ago

mdavis1506 liked this · 4 years ago -

rhcreations reblogged this · 4 years ago

rhcreations reblogged this · 4 years ago -

rhcreations liked this · 4 years ago

rhcreations liked this · 4 years ago -

justanoldfashiontumblog liked this · 4 years ago

justanoldfashiontumblog liked this · 4 years ago -

desdealgunlugardelsur reblogged this · 4 years ago

desdealgunlugardelsur reblogged this · 4 years ago -

desdealgunlugardelsur liked this · 4 years ago

desdealgunlugardelsur liked this · 4 years ago -

bowserisgay reblogged this · 4 years ago

bowserisgay reblogged this · 4 years ago -

bowserisgay liked this · 4 years ago

bowserisgay liked this · 4 years ago -

godzillawife liked this · 4 years ago

godzillawife liked this · 4 years ago -

sergioballester-blog reblogged this · 4 years ago

sergioballester-blog reblogged this · 4 years ago -

sergioballester-blog liked this · 4 years ago

sergioballester-blog liked this · 4 years ago -

klingonlesbian reblogged this · 4 years ago

klingonlesbian reblogged this · 4 years ago -

klingonlesbian liked this · 4 years ago

klingonlesbian liked this · 4 years ago -

apas-95 reblogged this · 4 years ago

apas-95 reblogged this · 4 years ago -

apas-95 liked this · 4 years ago

apas-95 liked this · 4 years ago -

sweetjedi reblogged this · 4 years ago

sweetjedi reblogged this · 4 years ago -

sweetjedi liked this · 4 years ago

sweetjedi liked this · 4 years ago -

shawn1965 liked this · 4 years ago

shawn1965 liked this · 4 years ago -

legacy-of liked this · 4 years ago

legacy-of liked this · 4 years ago -

pmartyr liked this · 4 years ago

pmartyr liked this · 4 years ago -

boxe14 liked this · 4 years ago

boxe14 liked this · 4 years ago -

laundrette liked this · 4 years ago

laundrette liked this · 4 years ago -

citk reblogged this · 4 years ago

citk reblogged this · 4 years ago -

electriccelery93 reblogged this · 4 years ago

electriccelery93 reblogged this · 4 years ago -

bookish-sapphic liked this · 4 years ago

bookish-sapphic liked this · 4 years ago -

galactic-aesir liked this · 4 years ago

galactic-aesir liked this · 4 years ago -

carac0lis liked this · 4 years ago

carac0lis liked this · 4 years ago