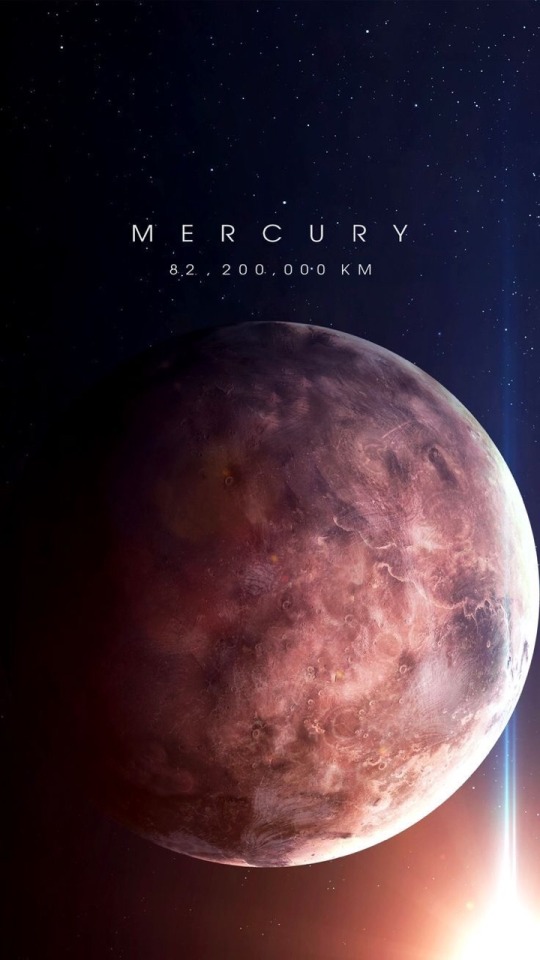

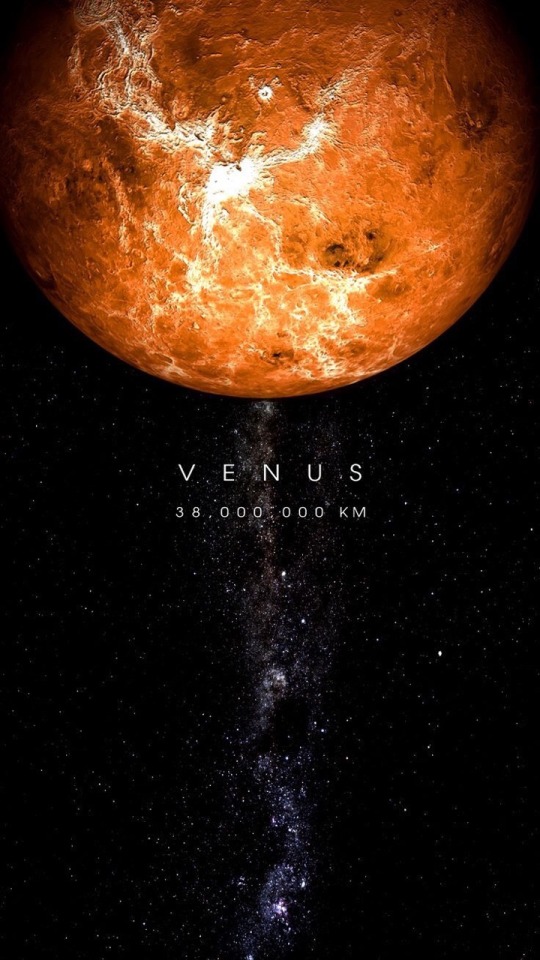

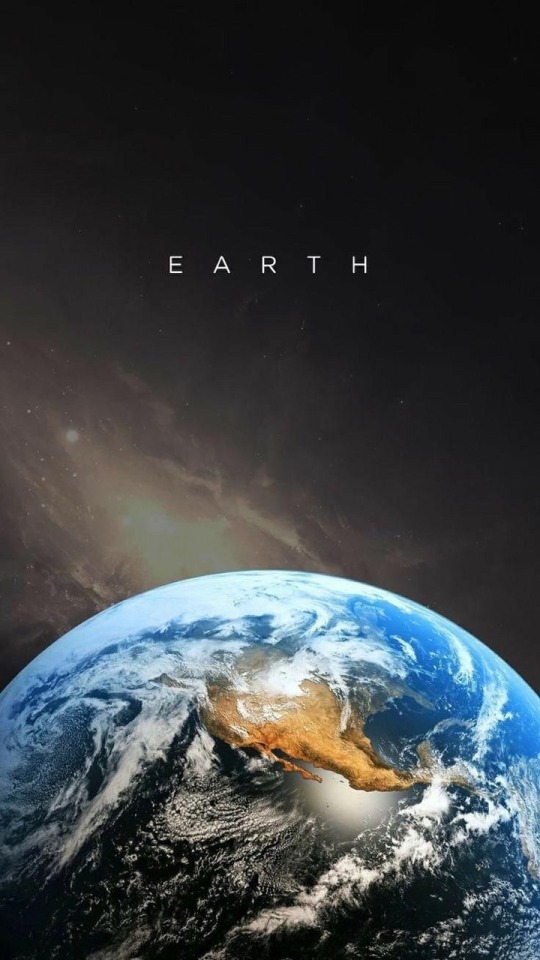

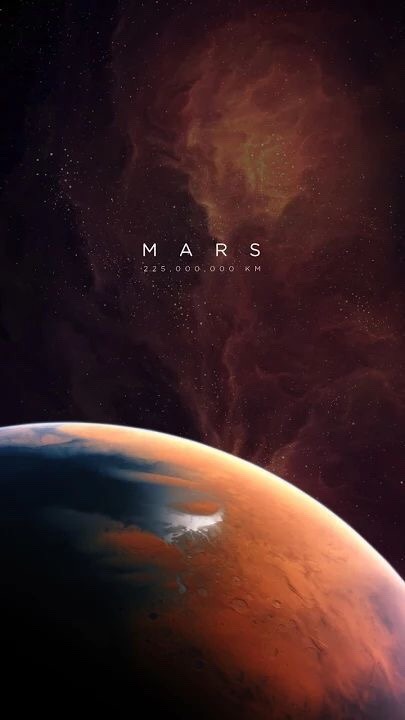

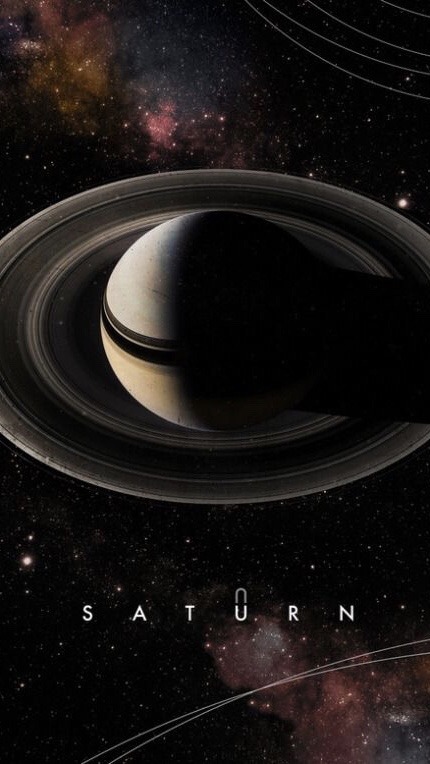

Solar System

Solar System

•please like or reblog if you use

More Posts from Sergioballester-blog and Others

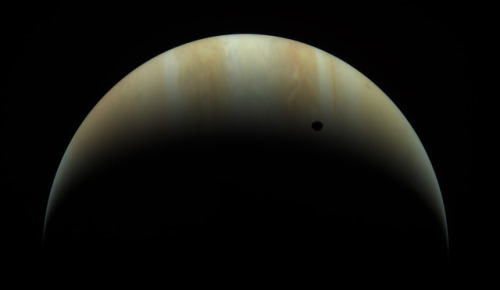

Grand Jupiter

Celebrating Five Years at Jupiter!

We just released new eye-catching posters and backgrounds to celebrate the five-year anniversary of Juno’s orbit insertion at Jupiter in psychedelic style.

On July 4, 2016, our Juno spacecraft arrived at Jupiter on a mission to peer through the gas giant planet’s dense clouds and answer questions about the origins of our solar system. Since its arrival, Juno has provided scientists a treasure trove of data about the planet’s origins, interior structures, atmosphere, and magnetosphere.

Juno is the first mission to observe Jupiter’s deep atmosphere and interior, and will continue to delight with dazzling views of the planet’s colorful clouds and Galilean moons. As it circles Jupiter, Juno provides critical knowledge for understanding the formation of our own solar system, the Jovian system, and the role giant planets play in putting together planetary systems elsewhere.

Get the posters and backgrounds here!

For more on our Juno mission at Jupiter, follow NASA Solar System on Twitter and Facebook.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

Jupiter and Europa

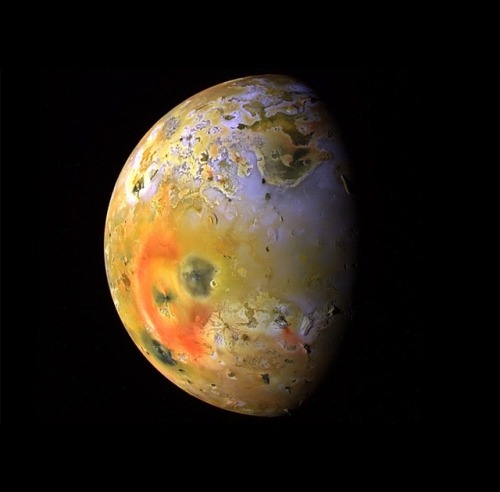

Jupiterʼs moons

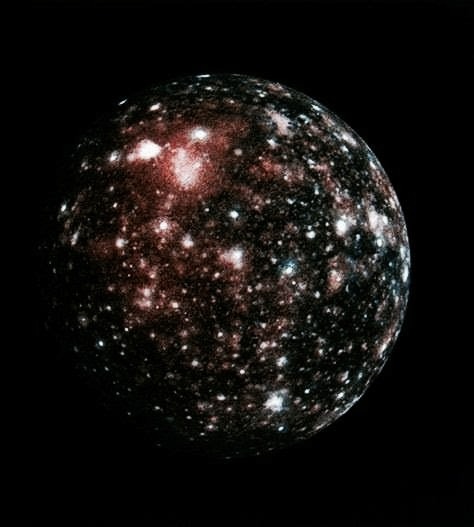

Ganymede, Callisto, Io and Europa

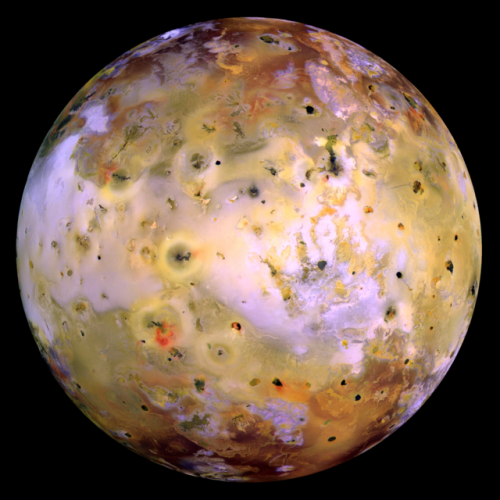

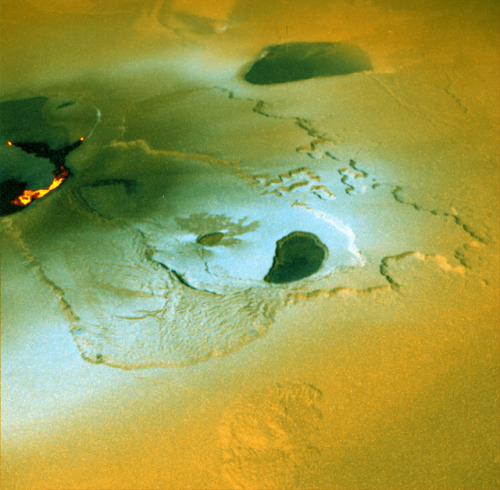

Io - The Volcanic Moon

Looking like a giant pizza covered with melted cheese and splotches of tomato and ripe olives, Io is the most volcanically active body in the solar system. Volcanic plumes rise 300 km (190 miles) above the surface, with material spewing out at nearly half the required escape velocity.

A bit larger than Earth’s Moon, Io is the third largest of Jupiter’s moons, and the fifth one in distance from the planet.

Although Io always points the same side toward Jupiter in its orbit around the giant planet, the large moons Europa and Ganymede perturb Io’s orbit into an irregularly elliptical one. Thus, in its widely varying distances from Jupiter, Io is subjected to tremendous tidal forces. These forces cause Io’s surface to bulge up and down (or in and out) by as much as 100 m (330 feet)! Compare these tides on Io’s solid surface to the tides on Earth’s oceans. On Earth, in the place where tides are highest, the difference between low and high tides is only 18 m (60 feet), and this is for water, not solid ground!

This tidal pumping generates a tremendous amount of heat within Io, keeping much of its subsurface crust in liquid form seeking any available escape route to the surface to relieve the pressure. Thus, the surface of Io is constantly renewing itself, filling in any impact craters with molten lava lakes and spreading smooth new floodplains of liquid rock. The composition of this material is not yet entirely clear, but theories suggest that it is largely molten sulfur and its compounds (which would account for the varigated coloring) or silicate rock (which would better account for the apparent temperatures, which may be too hot to be sulfur). Sulfur dioxide is the primary constituent of a thin atmosphere on Io. It has no water to speak of, unlike the other, colder Galilean moons. Data from the Galileo spacecraft indicates that an iron core may form Io’s center, thus giving Io its own magnetic field.

Io was discovered on 8 January 1610 by Galileo Galilei. The discovery, along with three other Jovian moons, was the first time a moon was discovered orbiting a planet other than Earth.

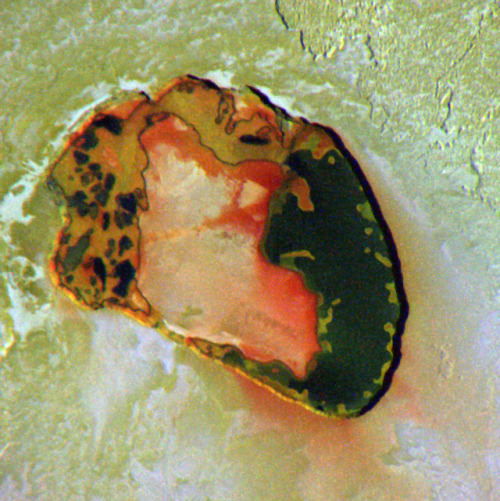

Eruption of the Tvashtar volcano on Jupiter’s moon Io, photographed by New Horizons.

Image credit: NASA/JPL/Galileo/New Horizons ( Stuart Rankin, Kevin Gill)

Source: NASA

Curiosity: Sol 3048 via NASA https://ift.tt/3vSSsDz

Perseverance: Amazing descent & landing video taken by the rover’s EDL cameras.

Sampling the ocean on Enceladus by europeanspaceagency

Grid fin hydraulic pump stalled, causing a soft water landing 🚀 POV shot.

Still most likely being reused in a CRS mission 🤘🏻

Perseverance: Some early Navcam (navigation camera) images taken over the (Earth) weekend on sol 2. Originals are here: [1] [2] [3] [4]. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

-

la-galleta-triste reblogged this · 1 month ago

la-galleta-triste reblogged this · 1 month ago -

ewokleader reblogged this · 2 months ago

ewokleader reblogged this · 2 months ago -

broken-jupiter liked this · 5 months ago

broken-jupiter liked this · 5 months ago -

annaub8z5 liked this · 7 months ago

annaub8z5 liked this · 7 months ago -

annita89e5qypoh liked this · 7 months ago

annita89e5qypoh liked this · 7 months ago -

anna35lxh liked this · 7 months ago

anna35lxh liked this · 7 months ago -

annita890dzmzfmh liked this · 8 months ago

annita890dzmzfmh liked this · 8 months ago -

aikiie liked this · 8 months ago

aikiie liked this · 8 months ago -

wk-all liked this · 10 months ago

wk-all liked this · 10 months ago -

iheartu1990 liked this · 11 months ago

iheartu1990 liked this · 11 months ago -

evelyn404 liked this · 1 year ago

evelyn404 liked this · 1 year ago -

bbiseuteu reblogged this · 1 year ago

bbiseuteu reblogged this · 1 year ago -

bbiseuteu liked this · 1 year ago

bbiseuteu liked this · 1 year ago -

kpop-bts-exo liked this · 1 year ago

kpop-bts-exo liked this · 1 year ago -

rfl0werssposts reblogged this · 1 year ago

rfl0werssposts reblogged this · 1 year ago -

rfl0werssposts liked this · 1 year ago

rfl0werssposts liked this · 1 year ago -

deepdarkdungeondubstep liked this · 1 year ago

deepdarkdungeondubstep liked this · 1 year ago -

tarot-freader liked this · 1 year ago

tarot-freader liked this · 1 year ago -

xiepergabbwiszenf liked this · 1 year ago

xiepergabbwiszenf liked this · 1 year ago -

pielustglycerchcul liked this · 1 year ago

pielustglycerchcul liked this · 1 year ago -

sigwealthxypuber liked this · 1 year ago

sigwealthxypuber liked this · 1 year ago -

dautilavesa liked this · 1 year ago

dautilavesa liked this · 1 year ago -

hypnotic-soul liked this · 1 year ago

hypnotic-soul liked this · 1 year ago -

laiflackieleb liked this · 1 year ago

laiflackieleb liked this · 1 year ago -

evolucion-1990 liked this · 1 year ago

evolucion-1990 liked this · 1 year ago