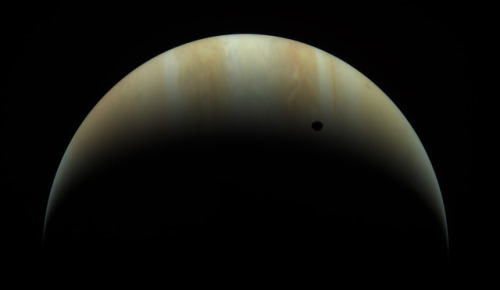

Jupiter And Europa

Jupiter and Europa

More Posts from Sergioballester-blog and Others

what is your favorite natural satellite?

Cassini’s farewell mosaic of Saturn by europeanspaceagency

Pluto’s Surface Changes Faster Than Earth’s, And A Subsurface Ocean Is Driving It

“These mountains aren’t static and stable, but rather are temporary water-ice mountains atop a volatile, nitrogen sea. The evidence for this comes from multiple independent observations. The mountains only appear between the hilly highlands, after the edge of a basin rim, and young plains with flowing canals. These young plains occur in Pluto’s heart-shaped lobe, which itself was caused by an enormous impact crater. Only a subsurface, liquid water ocean beneath the crust could cause the uplift we then see, leaving the nitrogen to fill it in.”

In July of 2015, NASA’s New Horizons Mission arrived at Pluto, photographing the world at the highest resolution ever, with some places getting as up-close as just 80 meters (260 feet) per pixel. Not bad for a world more than 3 billion miles (5 billion kilometers) from home! What we’ve learned is breathtaking. Rather than a static, frozen world, we found one with tons of evidence for active, interior geology, as well as with a changing surface that renews itself and undergoes cycles, quite unexpectedly to many. There’s also not an enormous heart, but rather a massive, volatile-filled crater that caused Pluto to tip over at least once in its past, and may yet cause it to tip over again in the near future.

If you ever wanted to know how these distant, icy worlds come alive, there’s never been a better way to find out than in the aftermath of what New Horizons taught us!

This impressive storm captured by Geoff Green over West Australia in August 2018, gives you an idea of the huge frequency at which lightning happen in an extreme weather event

Instagram: wonders_of_the_cosmos

Jupiter’s Racing Stripes by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center

Shuttle Endeavour’s flight deck. 🚀

NASA’s Search for Life: Astrobiology in the Solar System and Beyond

Are we alone in the universe? So far, the only life we know of is right here on Earth. But here at NASA, we’re looking.

We’re exploring the solar system and beyond to help us answer fundamental questions about life beyond our home planet. From studying the habitability of Mars, probing promising “oceans worlds,” such as Titan and Europa, to identifying Earth-size planets around distant stars, our science missions are working together with a goal to find unmistakable signs of life beyond Earth (a field of science called astrobiology).

Dive into the past, present, and future of our search for life in the universe.

Mission Name: The Viking Project

Launch: Viking 1 on August 20, 1975 & Viking 2 on September 9, 1975

Status: Past

Role in the search for life: The Viking Project was our first attempt to search for life on another planet. The mission’s biology experiments revealed unexpected chemical activity in the Martian soil, but provided no clear evidence for the presence of living microorganisms near the landing sites.

Mission Name: Galileo

Launch: October 18, 1989

Status: Past

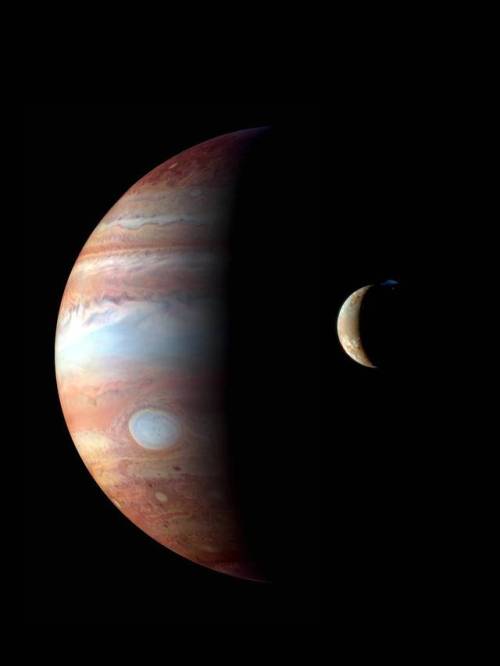

Role in the search for life: Galileo orbited Jupiter for almost eight years, and made close passes by all its major moons. The spacecraft returned data that continues to shape astrobiology science –– particularly the discovery that Jupiter’s icy moon Europa has evidence of a subsurface ocean with more water than the total amount of liquid water found on Earth.

Mission Name: Kepler and K2

Launch: March 7, 2009

Status: Past

Role in the search for life: Our first planet-hunting mission, the Kepler Space Telescope, paved the way for our search for life in the solar system and beyond. Kepler left a legacy of more than 2,600 exoplanet discoveries, many of which could be promising places for life.

Mission Name: Perseverance Mars Rover

Launch: July 30, 2020

Status: Present

Role in the search for life: Our newest robot astrobiologist is kicking off a new era of exploration on the Red Planet. The rover will search for signs of ancient microbial life, advancing the agency’s quest to explore the past habitability of Mars.

Mission Name: James Webb Space Telescope

Launch: 2021

Status: Future

Role in the search for life: Webb will be the premier space-based observatory of the next decade. Webb observations will be used to study every phase in the history of the universe, including planets and moons in our solar system, and the formation of distant solar systems potentially capable of supporting life on Earth-like exoplanets.

Mission Name: Europa Clipper

Launch: Targeting 2024

Status: Future

Role in the search for life: Europa Clipper will investigate whether Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, with its subsurface ocean, has the capability to support life. Understanding Europa’s habitability will help scientists better understand how life developed on Earth and the potential for finding life beyond our planet.

Mission Name: Dragonfly

Launch: 2027

Status: Future

Role in the search for life: Dragonfly will deliver a rotorcraft to visit Saturn’s largest and richly organic moon, Titan. This revolutionary mission will explore diverse locations to look for prebiotic chemical processes common on both Titan and Earth.

For more on NASA’s search for life, follow NASA Astrobiology on Twitter, on Facebook, or on the web.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

Arthur Strengthens, Moves Northward by NASA Goddard Photo and Video

July 20, 1969

Project Apollo on Flickr

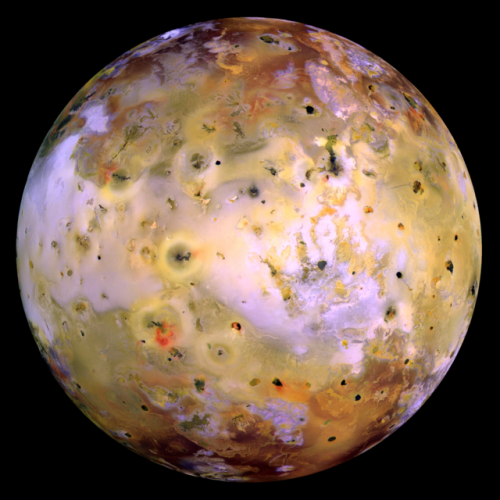

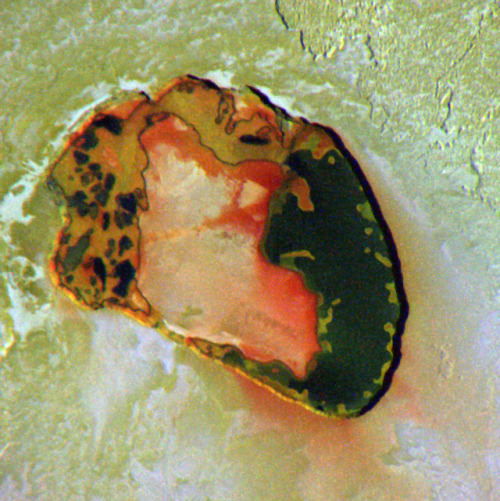

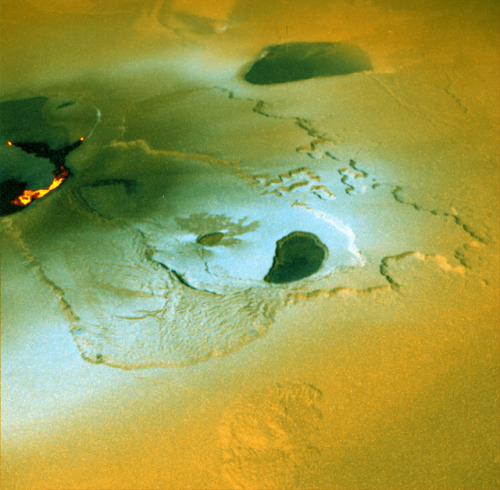

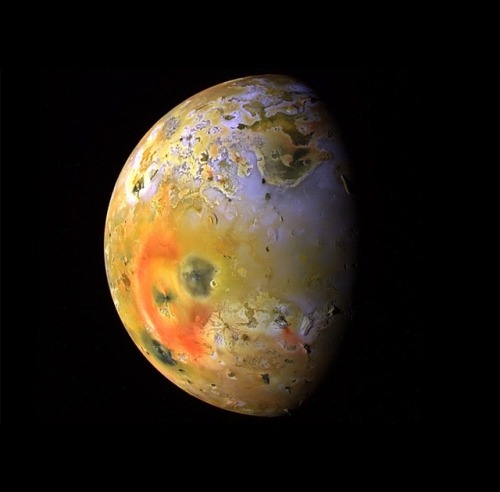

Io - The Volcanic Moon

Looking like a giant pizza covered with melted cheese and splotches of tomato and ripe olives, Io is the most volcanically active body in the solar system. Volcanic plumes rise 300 km (190 miles) above the surface, with material spewing out at nearly half the required escape velocity.

A bit larger than Earth’s Moon, Io is the third largest of Jupiter’s moons, and the fifth one in distance from the planet.

Although Io always points the same side toward Jupiter in its orbit around the giant planet, the large moons Europa and Ganymede perturb Io’s orbit into an irregularly elliptical one. Thus, in its widely varying distances from Jupiter, Io is subjected to tremendous tidal forces. These forces cause Io’s surface to bulge up and down (or in and out) by as much as 100 m (330 feet)! Compare these tides on Io’s solid surface to the tides on Earth’s oceans. On Earth, in the place where tides are highest, the difference between low and high tides is only 18 m (60 feet), and this is for water, not solid ground!

This tidal pumping generates a tremendous amount of heat within Io, keeping much of its subsurface crust in liquid form seeking any available escape route to the surface to relieve the pressure. Thus, the surface of Io is constantly renewing itself, filling in any impact craters with molten lava lakes and spreading smooth new floodplains of liquid rock. The composition of this material is not yet entirely clear, but theories suggest that it is largely molten sulfur and its compounds (which would account for the varigated coloring) or silicate rock (which would better account for the apparent temperatures, which may be too hot to be sulfur). Sulfur dioxide is the primary constituent of a thin atmosphere on Io. It has no water to speak of, unlike the other, colder Galilean moons. Data from the Galileo spacecraft indicates that an iron core may form Io’s center, thus giving Io its own magnetic field.

Io was discovered on 8 January 1610 by Galileo Galilei. The discovery, along with three other Jovian moons, was the first time a moon was discovered orbiting a planet other than Earth.

Eruption of the Tvashtar volcano on Jupiter’s moon Io, photographed by New Horizons.

Image credit: NASA/JPL/Galileo/New Horizons ( Stuart Rankin, Kevin Gill)

Source: NASA

-

freeehugss reblogged this · 3 months ago

freeehugss reblogged this · 3 months ago -

manucine liked this · 3 months ago

manucine liked this · 3 months ago -

cronamai reblogged this · 3 months ago

cronamai reblogged this · 3 months ago -

planebehindthemist reblogged this · 3 months ago

planebehindthemist reblogged this · 3 months ago -

leviathanxtreme reblogged this · 3 months ago

leviathanxtreme reblogged this · 3 months ago -

leviathanxtreme liked this · 3 months ago

leviathanxtreme liked this · 3 months ago -

cronamai liked this · 3 months ago

cronamai liked this · 3 months ago -

u-glob reblogged this · 3 months ago

u-glob reblogged this · 3 months ago -

grab2the2mods2and2leave liked this · 3 months ago

grab2the2mods2and2leave liked this · 3 months ago -

ourbillo reblogged this · 5 months ago

ourbillo reblogged this · 5 months ago -

ourbillo liked this · 5 months ago

ourbillo liked this · 5 months ago -

all-these-colors-in-me liked this · 5 months ago

all-these-colors-in-me liked this · 5 months ago -

marquisdesoie reblogged this · 5 months ago

marquisdesoie reblogged this · 5 months ago -

injunjoeisticklish reblogged this · 5 months ago

injunjoeisticklish reblogged this · 5 months ago -

injunjoeisticklish liked this · 5 months ago

injunjoeisticklish liked this · 5 months ago -

hummingbirdglimmer liked this · 5 months ago

hummingbirdglimmer liked this · 5 months ago -

astat3ofgrac3 reblogged this · 5 months ago

astat3ofgrac3 reblogged this · 5 months ago -

besessenp reblogged this · 5 months ago

besessenp reblogged this · 5 months ago -

besessenp liked this · 5 months ago

besessenp liked this · 5 months ago -

eennuyeuxx reblogged this · 5 months ago

eennuyeuxx reblogged this · 5 months ago -

gaiawatcher liked this · 5 months ago

gaiawatcher liked this · 5 months ago -

jazstarr liked this · 6 months ago

jazstarr liked this · 6 months ago -

youarenotyourblog reblogged this · 6 months ago

youarenotyourblog reblogged this · 6 months ago -

glikeriya-narkevich liked this · 6 months ago

glikeriya-narkevich liked this · 6 months ago -

bi-hans liked this · 6 months ago

bi-hans liked this · 6 months ago -

peijizerojournal reblogged this · 6 months ago

peijizerojournal reblogged this · 6 months ago -

iamsancho reblogged this · 6 months ago

iamsancho reblogged this · 6 months ago -

iamsancho liked this · 6 months ago

iamsancho liked this · 6 months ago -

sun-on-the-ceiling liked this · 6 months ago

sun-on-the-ceiling liked this · 6 months ago -

suic1de-life reblogged this · 6 months ago

suic1de-life reblogged this · 6 months ago -

gonerface reblogged this · 6 months ago

gonerface reblogged this · 6 months ago -

abihuluv2hate liked this · 7 months ago

abihuluv2hate liked this · 7 months ago -

trxllionaire liked this · 7 months ago

trxllionaire liked this · 7 months ago -

acolorofthewindd reblogged this · 7 months ago

acolorofthewindd reblogged this · 7 months ago -

mirrors-everywhere reblogged this · 7 months ago

mirrors-everywhere reblogged this · 7 months ago -

young-and-infinite-forever liked this · 7 months ago

young-and-infinite-forever liked this · 7 months ago -

protagx reblogged this · 7 months ago

protagx reblogged this · 7 months ago -

heathen-beast reblogged this · 7 months ago

heathen-beast reblogged this · 7 months ago -

tombs0123 liked this · 7 months ago

tombs0123 liked this · 7 months ago -

beardedcollectionphilosopher liked this · 7 months ago

beardedcollectionphilosopher liked this · 7 months ago -

superbrojira reblogged this · 7 months ago

superbrojira reblogged this · 7 months ago -

starbornb reblogged this · 7 months ago

starbornb reblogged this · 7 months ago -

mindwow reblogged this · 7 months ago

mindwow reblogged this · 7 months ago