George Harrison Smile Appreciation Post (1/?)

George Harrison smile appreciation post (1/?)

More Posts from Thusspokejade and Others

Bob Dylan and George Harrison having some fun in the studio.

Intermission in the Harrison cars series: Kinfauns goes psychedelic. (You can find a photo of George Harrison in front of the mural in the book Living In The Material World.) Photo 1 by Robert Whitaker, photo 2 courtesy of messynessychic dot com.

“During autumn [of 1967] George asked Simon and me to paint a mural around the fireplace in the living room at the ‘Kinfauns’ bungalow in Esher. The mural portrayed George and Pattie as ‘Music Boy’ and ‘Flower Girl,’ as they lovingly called each other then, attended by a Yogi surrounded with an Aura of Light as the focal point to express their interest in Hinduism. We stayed at their lovely place about ten days to complete it. Inspired, George started decorating the exterior of the house, graffiti style with spray cans […]. George was kind and funny but would also be quiet and pensive at times. […] George also turned us on to Paramahansa Yogananda’s book; ‘Autobiography of a Yogi,’ whose large portrait was watching us from the wall while we were painting the mural […].” - Marijke Koger, marijkekogerart dot com, 11 August 2021

“At that moment, an arm wrapped around me from behind, and even though I couldn’t see who it was, I knew it could only be George. He put his head on my right shoulder and gave me a cheeky grin and a sidelong glance. ‘What’s that under your nose, George?’ ‘It’s called a mustache.’ George put on a jokingly posh look and slowly brushed along his mustache with one finger. […] He pointed at his new fireplace. ‘Looks like a lot of work, doesn’t it? Look, there’s Krishna in the center.’ It seemed very important to George to have more and more symbols of Indian culture around him. While he stood next to me, with his long, full dark hair, the mustache and dark eyes sparkling with enthusiasm, he suddenly seemed like an Indian himself. He fully merged into this culture and way of life. George had found his path. […] George grabbed a paintbrush as well, and together with the Dutch gypsies we set to work on George’s fireplace.” - Klaus Voormann, translated from Warum spielst du Imagine nicht auf dem weißen Klavier, John? (2003) (x)

George Harrison during the filming of Magical Mystery Tour in Plymouth, England | 12 September 1967

18th December 1967, PARIS - George Harrison and Pattie Boyd attending at a UNICEF gala. (John & Cynthia Lennon can be seen at the second photo).

Photo by REPORTERS ASSOCIES/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

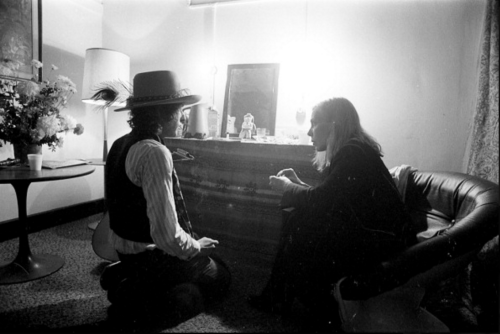

Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell, The Rolling Thunder Revue—Harvard Square Theater, Cambridge, MA, November 20, 1975 © Ken Regan.

George Harrison’s purple jacket, worn when he and John were on the David Frost Programme September 27, 1967. Designer unknown.

My scan from “You Say You Want a Revolution? Records and Rebels 1966-70.” This was the catalogue from the Victoria & Albert Museum exhibition of the same name. Book edited by Victoria Broackes and Geoffrey Marsh.

Teenagers >:)

To be a hero—in the most universal sense of the word—means to aspire to absolute triumph. But such triumphs come only through death. Heroism means transcending life; it is a fatal leap into nothingness.

Emil Cioran, “Disintegration,” On the Heights of Despair (via emilcioran)

excited for the Let It Be remaster coming out soon so we can see john and george singing “You’ve Really Got a Hold on Me” to each other in HD

George Harrison remained an enigma to many people, even those who were close to him. For a man who lectured passionately about karma and the meaning of existence, he seemed self-protective and closed off. Witty when called upon, there were also moments when he could be quite boorish. Perhaps it was because he was only twenty years old when the Beatles became a global sensation. That might not seem particularly young in today’s world of social media fame, but at the time, it was uncharted territory for the kind of adulation he was experiencing.

It was also difficult living in the shadow of Paul and John. In the beginning, they were openly dismissive of him. Paul said he always thought of George as a little brother. At first, John pretended not to know his name and sardonically referred to him as “that kid’’. Ironically, one of George’s compositions, Something, became the most covered song in the Beatles catalogue.

This interview was conducted at George Harrison’s palatial home, Friar Park, in Henley-on-Thames, on November 5, 1980. George was gracious but cool. He made a pot of tea in the drafty, vast kitchen of his 120-room estate, and spent two hours lecturing about Transcendental Meditation and the details of a limited edition of his autobiography, I Me Mine, which is certainly how he must have felt getting out on his own.

In 2000, George was diagnosed with oropharyngeal cancer. George died on November 29, 2001, in the company of his wife, Olivia; his son, Dhani; musician Ravi Shankar; and Hare Krishna devotees who chanted verses from the Bhagavad Gita. He was 58 years old and left nearly $100 million in his will. George told Olivia that he didn’t want to be remembered for being a Beatle, he wanted to be remembered for being a good gardener.

‘It was a transcendental experience that was beyond the mind’

On taking LSD

LSD was just such a violent, big experience. Before it I was totally ignorant, and afterward I knew I was totally ignorant and I was now on my way to having some sort of knowledge. I related it to the childhood experience of Catholicism and going to church on a Sunday and seeing all that phoney baloney. The moment I’d taken LSD, it just made me laugh because I understood it inside, just in a flash. I understood what the whole concept of God or religion was just by seeing it. I could see it in the grass in the trees.

It was an absolute truth; like a light going ching. I took three very powerful trips — big, very important — and then it left me a bit unsure because I had to try and figure something out. By that time I had gotten into Indian music and spent time in India, [and] there was so much about it that felt like home to me. Not the surface that you see — all this poverty and the flies and the shit everywhere — [it] went beyond all that. Smells in the atmosphere and the people’s attitude and the music, the food, the religion, everything about it … home.

‘I’d hear his voice wailing at five in the morning’

On the death of Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones

I liked Brian a lot, and later on, I realised it was probably because we were both Pisces. We both had similar natures. He was also similar in that he had a Keith and a Mick, whereas I had a John and a Paul. We both had that problem of two mighty egos to deal with in order just to try and survive. I was very susceptible to dope, and Brian [Jones] was even more susceptible. He’d come [to my house], and I’d just hear his voice wailing at like five in the morning: “George, Geeooorrgggeeee.” So I’d wake up, see what was going on, and I’d look out the window, and he’d be all white and just shattered walking around the garden — just looking for somewhere to be.

I would always meet him at that time of day and just try to calm him down. And I saw him a lot before he died in that sort of circumstance. The last time I saw him, I think, was when I’d been in hospital to have my tonsils out and he came to see me in hospital and the next week he was gone. He was like all of them who kicked the bucket — it was sad because there were too many pressures, really. Not just the pressure of being famous and having the press hounding you day and night and young fans hounding you day and night. Plus the drugs hounding you day and night.

‘F*** it — I could do better than that’

On his childhood inspiration, Cliff Richard

I remember being a kid of about twelve, dreaming of big motorboats and tropical islands and things which had nothing to do with Liverpool, which was dark and cold. I remember going to see Cliff Richard and thinking, f*** it — I could do better than that.

‘I think being Elvis was lonelier than being one of the Fab Four’

On fame — and Elvis Presley

We kept realising we were getting bigger and bigger until we all realised we couldn’t go anywhere —you couldn’t pick up a paper or turn on a radio or TV without seeing yourself. I mean, it became too much. We became trapped, and that’s why it had to end, is what I think … We were like monkeys in a cage. I think it was helped a bit by the fact that it was four of us, who shared the experience. I mean, there was more than four of us, there was Peter Brown and Brian Epstein, but there was only four of us who were actually the Fab Four — whereas Elvis had an entourage and maybe 15 guys, friends of his, but there was only one man having that experience of what it was like to be Elvis Presley. I think that was far lonelier than being one of the Fab Four because at least we could keep each other laughing or crying or whatever we did to each other. It was definitely an asset being in a group.

(source)

-

alanangels liked this · 2 months ago

alanangels liked this · 2 months ago -

thusspokejade reblogged this · 1 year ago

thusspokejade reblogged this · 1 year ago -

thusspokejade liked this · 1 year ago

thusspokejade liked this · 1 year ago -

stinkyfartgirl liked this · 1 year ago

stinkyfartgirl liked this · 1 year ago -

chaos-from-basil liked this · 2 years ago

chaos-from-basil liked this · 2 years ago -

ineffibleohfuck liked this · 2 years ago

ineffibleohfuck liked this · 2 years ago -

boingodigitalart liked this · 2 years ago

boingodigitalart liked this · 2 years ago -

nuvemzinhacorderosa reblogged this · 2 years ago

nuvemzinhacorderosa reblogged this · 2 years ago -

nuvemzinhacorderosa liked this · 2 years ago

nuvemzinhacorderosa liked this · 2 years ago -

taxman2022mix liked this · 2 years ago

taxman2022mix liked this · 2 years ago -

doofusschweetz liked this · 2 years ago

doofusschweetz liked this · 2 years ago -

times-up-alone-tonight liked this · 2 years ago

times-up-alone-tonight liked this · 2 years ago -

bobdylans116thdream reblogged this · 2 years ago

bobdylans116thdream reblogged this · 2 years ago -

andyourbirdcansing-take2 reblogged this · 2 years ago

andyourbirdcansing-take2 reblogged this · 2 years ago -

hands-across-the-sky liked this · 2 years ago

hands-across-the-sky liked this · 2 years ago -

bridgeoverstrawberryfields reblogged this · 2 years ago

bridgeoverstrawberryfields reblogged this · 2 years ago -

bridgeoverstrawberryfields liked this · 2 years ago

bridgeoverstrawberryfields liked this · 2 years ago -

inactivemax reblogged this · 2 years ago

inactivemax reblogged this · 2 years ago -

inactivemax liked this · 2 years ago

inactivemax liked this · 2 years ago -

skipperthekangaroo reblogged this · 2 years ago

skipperthekangaroo reblogged this · 2 years ago -

therockywhorerpictureshow liked this · 2 years ago

therockywhorerpictureshow liked this · 2 years ago -

mindofotherstars reblogged this · 2 years ago

mindofotherstars reblogged this · 2 years ago -

mindofotherstars liked this · 2 years ago

mindofotherstars liked this · 2 years ago -

leyley09 reblogged this · 2 years ago

leyley09 reblogged this · 2 years ago -

morewyckedthanyou reblogged this · 2 years ago

morewyckedthanyou reblogged this · 2 years ago -

hoopdiddydiddy reblogged this · 2 years ago

hoopdiddydiddy reblogged this · 2 years ago -

hoopdiddydiddy liked this · 2 years ago

hoopdiddydiddy liked this · 2 years ago -

soontobeyfree reblogged this · 2 years ago

soontobeyfree reblogged this · 2 years ago -

raspberrytoupee reblogged this · 2 years ago

raspberrytoupee reblogged this · 2 years ago -

mijacoge0 liked this · 2 years ago

mijacoge0 liked this · 2 years ago -

juicebox-bside liked this · 2 years ago

juicebox-bside liked this · 2 years ago -

honkycats reblogged this · 2 years ago

honkycats reblogged this · 2 years ago -

honkycats liked this · 2 years ago

honkycats liked this · 2 years ago -

riuchiu liked this · 2 years ago

riuchiu liked this · 2 years ago -

sheet-metal-memories reblogged this · 2 years ago

sheet-metal-memories reblogged this · 2 years ago -

yellowcurrant liked this · 2 years ago

yellowcurrant liked this · 2 years ago -

mcstarr reblogged this · 2 years ago

mcstarr reblogged this · 2 years ago -

mcstarr liked this · 2 years ago

mcstarr liked this · 2 years ago -

madotsuki liked this · 2 years ago

madotsuki liked this · 2 years ago -

tantamount-treason liked this · 2 years ago

tantamount-treason liked this · 2 years ago -

harrisonsbiscuit reblogged this · 2 years ago

harrisonsbiscuit reblogged this · 2 years ago -

mrsparasol reblogged this · 2 years ago

mrsparasol reblogged this · 2 years ago -

bilbao-song reblogged this · 2 years ago

bilbao-song reblogged this · 2 years ago -

bilbao-song liked this · 2 years ago

bilbao-song liked this · 2 years ago -

itbe1964 reblogged this · 2 years ago

itbe1964 reblogged this · 2 years ago -

bahrlee liked this · 2 years ago

bahrlee liked this · 2 years ago