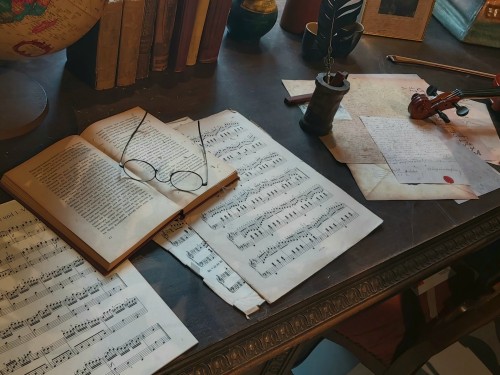

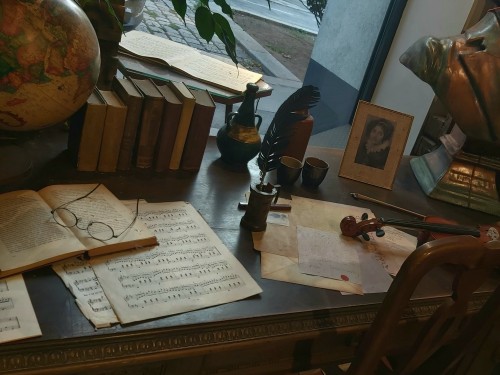

Fragments Of A Beethovenfest Deko I Found At A Thrift Store In Vienna - 2020

Fragments of a Beethovenfest deko I found at a thrift store in Vienna - 2020

More Posts from Theblogofwildfellhall and Others

And this year for Halloween I am a lazy pirate

Rrrrrrr

Le Petit Prince - quotes 🌠

Le Petit Prince (1943) is a novel by Antoine de Saint Exupéry, translated into English as The Little Prince.

🌟 1. Les grandes personnes ne comprennent jamais rien toutes seules, et c’est fatigant, pour les enfants, de toujours et toujours leur donner des explications.

Grown-ups never understand anything by themselves, and it is tiresome for children to be always and forever explaining things to them.

🌟 2. Quand le mystère est trop impressionnant, on n’ose pas désobéir.

When a mystery is too overpowering, one dare not disobey.

🌟 3. La preuve que le petit prince a existé c’est qu’il était ravissant, qu’il riait, et qu’il voulait un mouton. Quand on veut un mouton, c’est la preuve qu’on existe.

The proof that the little prince existed is that he was charming, that he laughed, and that he was looking for a sheep. If anybody wants a sheep, that is a proof that he exists.

🌟 4. Mais les graines sont invisibles. Elles dorment dans le secret de la terre jusqu’à ce qu’il prenne fantaisie à l’une d’elles de se réveiller…

But seeds are invisible. They sleep deep in the heart of the earth’s darkness, until some one among them is seized with the desire to awaken.

🌟 5. Il ne faut jamais écouter les fleures. Il faut les regarder et les respirer. La mienne embaumait ma planète, mais je ne savais pas m’en réjouir.

One never ought to listen to the flowers. One should simply look at them and breathe their fragrance. Mine perfumed all my planet. But I did not know how to take pleasure in all her grace.

🌟 6. Tu as des cheveux couleur d’or. Alors ce sera merveilleux quand tu m’aura apprivoisé! Le blé, qui est doré, me fera souvenir de toi. Et j’aimerai le bruit du vent dans le blé…

You have hair that is the color of gold. Think how wonderful that will be when you have tamed me! The grain, which is also golden, will bring me back the thought of you. And I shall love to listen to the wind in the wheat…

🌟 7. On ne connaît que les choses que l’on apprivoise, dit le renard. Les hommes n’ont plus le temps de rien connaître. Il achètent des choses toutes faites chez les marchands. Mais comme il n’existe point de marchands d’amis, les hommes n’ont plus d’amis. Si tu veux un ami, apprivoise-moi!

“One only understands the things that one tames,” said the fox. “Men have no more time to understand anything. They buy things all ready made at the shops. But there is no shop anywhere where one can buy friendship, and so men have no friends any more. If you want a friend, tame me…”

🌟 8. Le langage est source de malentendus.

Words are the source of misunderstandings.

🌟 9. Voici mon secret. Il est très simple : on ne voit bien qu’avec le coeur. L’essentiel est invisible pour les yeux.

And now here is my secret, a very simple secret: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.

🌟 10. C’est le temps que tu as perdu pour ta rose qui fait ta rose si importante.

It is the time you have wasted for your rose that makes your rose so important.

🌟 11. Tu deviens responsable pour toujours de ce que tu as apprivoisé. Tu es responsable de ta rose…

You become responsible, forever, for what you have tamed. You are responsible for your rose…

🌟 12. - Les enfants seuls savent ce qu’ils cherchent, fit le petit prince. Ils perdent du temps pour une poupée de chiffons, et elle devient très importante, et si on la leur enlève, ils pleurent…

“Only the children know what they are looking for,” said the little prince. “They waste their time over a rag doll and it becomes very important to them; and if anybody takes it away from them, they cry…”

🌟 13. Ce qui embellit le désert, dit le petit prince, c’est qu’il cache un puits quelque part…

“What makes the desert beautiful,” said the little prince, “is that somewhere it hides a well…”

🌟 14. Dessine-moi un mouton!

Draw me a sheep!

🌟 15. Quand on a terminé sa toilette du matin, il faut faire soigneusement la toilette de la planète.

When you’ve finished getting yourself ready in the morning, you must go get the planet ready.

🌟 16. J'aime bien les couchers de soleil. Allons voir un coucher de soleil…

I am very fond of sunsets. Come, let us go look at a sunset…

🌟 17. On ne sait jamais!

“One never knows!”

🌟 18. Il faut exiger de chacun ce que chacun peut donner, reprit le roi. L'autorité repose d'abord sur la raison. Si tu ordonnes à ton peuple d'aller se jeter à la mer, il fera la révolution. J'ai le droit d'exiger l'obéissance parce que mes ordres sont raisonnables. Alors mon coucher de soleil ? rappela le petit prince qui jamais n'oubliait une question une fois qu'il l'avait posée. Ton coucher de soleil, tu l'auras. Je l'exigerai. Mais j'attendrai, dans ma science du gouvernement, que les conditions soient favorables.

“One must command from each what each can perform,” the king went on. “Authority is based first of all upon reason. If you command your subjects to jump into the ocean, there will be a revolution. I am entitled to command obedience because my orders are reasonable.” “Then my sunset?” insisted the little prince, who never let go of a question once he had asked it. “You shall have your sunset. I shall command it. But I shall wait, according to my science of government, until conditions are favorable.”

🌟 19. C'est véritablement utile puisque c'est joli.

It is truly useful since it is beautiful.

🌟 20. ‘Où sont les hommes ?’ reprit enfin le petit prince. 'On est un peu seul dans le désert.’ 'On est seul aussi chez les hommes’, dit le serpent.

“Where are the people?” resumed the little prince at last. “It’s a little lonely in the desert…" "It is lonely when you’re among people, too,” said the snake.

🌟 21. Vous êtes belles, mais vous êtes vides…. On ne peut pas mourir pour vous.

You’re beautiful, but you’re empty…. No one could die for you.

🌟 22. Les hommes ont oublié cette vérité, dit le renard. Mais tu ne dois pas l’oublier. Tu deviens responsable pour toujours de ce que tu as apprivoisé.

“Men have forgotten this truth,” said the fox. “But you must not forget it. You become responsible, forever, for what you have tamed.”

🌟 23. Mais les yeux sont aveugles. Il faut chercher avec le cœur.

But the eyes are blind. One must look with the heart…

Classic Horror Novels That Are NOT Frankenstein Or Dracula

The Vampyre by John William Polidori

Carmilla by J. Sharidon le Fanu

The Flowers Of Evil by Charles Baudelaire

Perfume: The Story Of A Murderer by Patrick Suskind & translated by John E. Woods

The Strange Case Of Doctor Jekyll & Mister Hyde by John Louis Stevenson

Complete Stories & Poems by Edgar Allen Poe

The Picture Of Dorian Grey by Oscar Wild

The Turn Of The Screw by Henry James

The Island Of Doctor Moreau by H.G. Wells

The Hounds Of Baskerville by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Monk by Matthew Gregory Lewis

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte

The Legend Of Sleepy Hollow by Washington Irving

Uncle Silas by J. Sheridan le Fanu

Melmoth The Wanderer by Charles Robert Maturin

The Woman In White by Wilkie Collins

*Note these are all novels published BEFORE the 1900s -- I've got a whole other list of those. If you're interested, hmu.

Le Passé Composé - Masterpost

The passé composé is the most commonly used past tense in French.

It is formed using the following formula:

subject + avoir or être (conjugated in the present tense) + past participle

Conjugating avoir and être

In the present tense, avoir (to have) is conjugated as follows:

je - ai ¹ | nous - avons

tu - as | vous - avez

il/elle/on - a | ils/elles - ont ²

In the present tense, être (to be) is conjugated as follows:

je - suis | nous - sommes

tu - es | vous - êtes

il/elle/on - est | ils/elles - sont

Forming the past participle

For regular -er verbs, drop -er and add -é (parler → parlé)

For regular -re verbs, drop -re and add -u (vendre → vendu)

For regular -ir verbs , drop -ir and add -i (finir → fini)

Forms of past participles:

Nearly all past participles use the following endings to indicate gender and number:

__Masculine__|__Feminine____

Singular | é / u / i | ée / ue / ie

Plural | és / us / is | ées / ues / ies

Common irregular past participles:

être (to be) → été

faire (to do, make) → fait ³

offrir (to offer) → offert ³

ouvrir (to open) → ouvert ³

naître (to be born) → né

mourir (to die) → mort ³

avoir (to have) → eu

boire (to drink) → bu

connaître (to know) → connu

coire (to believe) → cru

devoir (must; to owe) → dû

lire (to read) → lu

pleuvoir (to rain) → plu

pouvoir (can; to be able to) → pu

recevoir (to receive) → reçu

savoir (to know) → su

voir (to see) → vu

vouloir (to want) → voulu

venir (to come) → venu

mettre (to place) → mis ³

prendre (to take) → pris ³

conduire (to drive) → conduit ³

dire (to say)→ dit ³

écrire (to write) → écrit ³

asseoir (to sit down) → assis ³

Irregular verbs formed from other irregular verbs use the same base for their past participles:

mettre → mis; permettre (to permit, allow) → permis

ouvrir → ouvert; couvrir (to cover) → couvert

When to use avoir or être

The majority of French verbs use avoir in the passé composé. Default to avoir, barring the following exceptions:

The following verbs usually use être as its auxilary verb ⁴ in the passé composé. They often have to do motion, but not all verbs of motion use être . They therefore must be memorized.

aller - to go

arriver - to arrive

descendre ⁵ - to descend / go downstairs

entrer ⁵ - to enter

monter ⁵ - to climb

mourir - to die

naître ⁵ - to be born

partir ⁵ - to leave

passer - to pass

rester - to stay

retourner - to return

sortir ⁵ - to go out

tomber ⁵ - to fall

venir ⁶ - to come

All pronominal verbs, without exception, use être in the passé composé.

Agreement in the passé composé

Agreement with avoir

The past participle normally agrees in gender and number with the direct object (or direct object pronoun) if it precedes the verb, barring the exceptions that follow.

J’ai lu les lettres. (I read the letters.)

Je les ai lues. (I read them.)

J’ai ouvert les lettres. (I opened the letters.)

Les lettres qui j’ai ouvertes sont lá-bas. (The letters that I opened are over there.)

Exceptionally, the past participle does not have to agree with the direct object in causative constructions or with certain constructions with verbs of perception ⁷.

Je les a fait lire les lettres. (I made them read the letters.)

Les lettres que j’ai vu écrire. (I saw the letters get written.)

Agreement with être

The past participle must always agree with the subject with non-pronominal verbs that use être.

Elle est allée à la poste pour déposer les lettres. (She went to the post office to drop off the letters.)

Vous êtes parties de la poste avec les lettres. (You (f.pl.) left the post office with the letters.)

The past participle must agree with the reflexive pronoun of pronominal verbs when the reflexive pronoun is the direct object. It does not agree with the indirect object.

Elle s’est asisse à son bureau quand elle lisait la lettre. (She sat herself down at her desk when she was reading the letter.

Nous nous sommes envoyés des lettres. (We sent each other letters.)

Negating in the passé composé

Add the standard ne… pas construction around avoir or être, excluding the subject and past participle. Include objective and adverbial pronouns that precede the auxiliary verb ⁸. When using inversion, include the subject and the verb between the negative constructions.

Je n’ai pas écrit ces lettres (I did not write those letters.)

Je ne les ai pas écrits ces lettres. (I did not write them.)

Je ne suis pas allé à la poste pour déposer les lettres. (I did not go to the post office to drop off the letters.)

Je n’y suis pas allé. (I did not go there.)

N’êtes-vous pas retournés de la poste ? (Did you return from the post office?)

Questioning in the passé composé

Questions are formed in the passé composé using the inversion or est-ce que constructions.

Avez-vous déja écrit les lettres ? (Do you write the letters yet?)

Est-ce qu’ils sont allés à la poste ? (Did they go to the post office?)

Pourquoi n’avez-vous pas envoyé les lettres ? (Why did you not send the letters?)

Questions can be asked informally using standard SVO word order with a question tone at the end of the sentence.

Tu as déja envoyé les lettres ? (You sent the letters already?)

Translating the passé composé

The passé composé can be translated as [verb + ed], [to have + past participle] or [did / do + verb].

J’ai écrit les lettres. (I wrote / have written / did write the letters.)

¹ je and ai are elided as j’ai.

² Be sure to liaise the s and o to distinguish it from sont, the third person plural form of être.

³ These verbs use irregular past participle forms to indicate gender and number:

Fait, ouvert, offert, conduit, écrit, dit, and mort use the following:

_______|__Masculine__|__Feminine__

Singular | ∅ | e

Plural | s | es

Mis, pris, and assis use the following:

_______|__Masculine__|__Feminine__

Singular | ∅ | e

Plural | ∅ | es

⁴ when used intransitively. When they take a direct object, they use avoir instead.

⁵ These verbs can add re- to make verbs that indicate that the action was repeated; these derivatives use être as well.

⁶ venir has the following derivatives: devenir (to become), parvenir (to reach, achieve), and revenir (to come again, come back); these use être as well.

⁷ The six verbs of perception are apercevoir (to catch a glimpse of), écouter (to listen) entendre (to hear), regarder (to watch), sentir (to feel), and voir (to see); the past participle never agrees with the direct object of the infinitive; the past participle agrees with the subject of the infinitive when it precedes the verb.

⁸ Objective and adverbial pronouns precede the auxiliary verb and succeed the subject.

how to sound more like a french native speaker 🌿

The following points are 5 classic French conversational techniques and mannerisms to help you sound just a bit more truly français:

1. The tactical use of bah

Fairly difficult to translate, the French bah is used rather regularly and can make your speech pattern sound very authentic.

In answer to an obvious question perhaps:

“Tu aimes bien la pizza?” (Do you like pizza?)

“Bah oui, bien sur!” (Well, yes, of course!)

Or something like the following:

“Tu adores le brocoli?” (Do you love broccoli?)

“Bah non! Je déteste!” (No, I hate it!)

Or as a deep, elongated syllable to fill gaps while you think:

“Qu’est-ce que tu fais le weekend?” (What are you doing on the weekend?)

“Baaaaaahh, en fait je ne sais pas encore.” (Well…actually I don’t know yet)

2. Add quoi to the ends of sentences

This one is also not easy to translate, but it would be the French equivalent of “whatever” or “innit.” So, you might imagine that it shouldn’t be used when talking formally, but it’s used often in casual conversation and can perfectly round off a sentence.

“C’est quoi, ça?” (What is that?)

“Euuh, je ne sais pas exactement mais je pense que c’est une sorte de nourriture, quoi.” (Um, I’m not really sure but I think it’s a type of food or whatever.)

3. Using eh, ah and hein like there’s no tomorrow

Whether it’s to fill space while you think or to provoke a response, these elongated vowels are very useful when speaking French. They can be heard very often in conversation.

For example, in English we add “don’t you?”/ “aren’t you?”/ “isn’t it?” to the end of statements to toss the conversational ball back into the other person’s court. The French will simply say “hein?”

“Il fait beau aujourd’hui hein?” (It’s nice weather today isn’t it?)

Try it with raised eyebrows for added French effect.

4. Sufficient use of voilà here, there and everywhere

The slangy English phrases “so, yeah” or “so, there you go” would probably be best translated into French as “voilà.”

When you can’t think of anything else to say at the end of a sentence, you can’t go wrong with a voilà. Sometimes even two. Voilà voilà.

5. Not forgetting the classic French shrug

In response to a question to which you don’t know the answer, respond the French way with an exaggerated shrug, raised eyebrows and add a “baaah, je sais pas, moi!” for good measure.

"Hope is a waking dream"

- Aristotle

(a concept playlist)

I want to say I can't believe my dad's girlfriend would set me up for theft, but here we are.

-

fuegodemetralla reblogged this · 2 months ago

fuegodemetralla reblogged this · 2 months ago -

cherubuns reblogged this · 2 months ago

cherubuns reblogged this · 2 months ago -

gianababes-blog liked this · 2 months ago

gianababes-blog liked this · 2 months ago -

dokush-a liked this · 2 months ago

dokush-a liked this · 2 months ago -

rabbitstudy reblogged this · 2 months ago

rabbitstudy reblogged this · 2 months ago -

balladofareader liked this · 2 months ago

balladofareader liked this · 2 months ago -

midniighthollow reblogged this · 3 months ago

midniighthollow reblogged this · 3 months ago -

lacitateuse reblogged this · 3 months ago

lacitateuse reblogged this · 3 months ago -

follow-mothmantis liked this · 3 months ago

follow-mothmantis liked this · 3 months ago -

desbotarias reblogged this · 3 months ago

desbotarias reblogged this · 3 months ago -

squishyy-squid liked this · 3 months ago

squishyy-squid liked this · 3 months ago -

thetimerewind reblogged this · 3 months ago

thetimerewind reblogged this · 3 months ago -

heroingrrrl liked this · 3 months ago

heroingrrrl liked this · 3 months ago -

hypn0sfr liked this · 3 months ago

hypn0sfr liked this · 3 months ago -

justafreeoldsoul liked this · 3 months ago

justafreeoldsoul liked this · 3 months ago -

academeia reblogged this · 3 months ago

academeia reblogged this · 3 months ago -

bellaiw liked this · 3 months ago

bellaiw liked this · 3 months ago -

justlikeotherchemists reblogged this · 4 months ago

justlikeotherchemists reblogged this · 4 months ago -

tomhardyslefteye liked this · 4 months ago

tomhardyslefteye liked this · 4 months ago -

gotta-love-living reblogged this · 5 months ago

gotta-love-living reblogged this · 5 months ago -

musingsofminerva reblogged this · 5 months ago

musingsofminerva reblogged this · 5 months ago -

modernpersephone reblogged this · 5 months ago

modernpersephone reblogged this · 5 months ago -

adreamgonewild reblogged this · 5 months ago

adreamgonewild reblogged this · 5 months ago -

sapphic--witch reblogged this · 5 months ago

sapphic--witch reblogged this · 5 months ago -

ophielina liked this · 5 months ago

ophielina liked this · 5 months ago -

viktorfrnkenstein liked this · 5 months ago

viktorfrnkenstein liked this · 5 months ago -

fandomloverfan liked this · 5 months ago

fandomloverfan liked this · 5 months ago -

honeyed-sunflowers liked this · 5 months ago

honeyed-sunflowers liked this · 5 months ago -

retratosehistorias reblogged this · 5 months ago

retratosehistorias reblogged this · 5 months ago -

coffetable reblogged this · 5 months ago

coffetable reblogged this · 5 months ago -

timesnewrona liked this · 5 months ago

timesnewrona liked this · 5 months ago -

suncarnation reblogged this · 5 months ago

suncarnation reblogged this · 5 months ago -

halfwaysleeping reblogged this · 5 months ago

halfwaysleeping reblogged this · 5 months ago -

academeia reblogged this · 5 months ago

academeia reblogged this · 5 months ago -

seventimesround liked this · 5 months ago

seventimesround liked this · 5 months ago -

passion-and-demise reblogged this · 5 months ago

passion-and-demise reblogged this · 5 months ago -

nocturnalxsaturn liked this · 5 months ago

nocturnalxsaturn liked this · 5 months ago -

ofdirtandbones liked this · 5 months ago

ofdirtandbones liked this · 5 months ago -

partium-deest reblogged this · 5 months ago

partium-deest reblogged this · 5 months ago -

abeille-petite reblogged this · 5 months ago

abeille-petite reblogged this · 5 months ago -

mvssive liked this · 5 months ago

mvssive liked this · 5 months ago -

floralbeasts reblogged this · 5 months ago

floralbeasts reblogged this · 5 months ago -

floralbeasts liked this · 5 months ago

floralbeasts liked this · 5 months ago -

crowcottagecore reblogged this · 5 months ago

crowcottagecore reblogged this · 5 months ago -

crowcottagecore liked this · 5 months ago

crowcottagecore liked this · 5 months ago -

dieselwayfarer liked this · 5 months ago

dieselwayfarer liked this · 5 months ago -

academeia reblogged this · 5 months ago

academeia reblogged this · 5 months ago -

reclusiveshaddows liked this · 5 months ago

reclusiveshaddows liked this · 5 months ago -

clairesmoldychips liked this · 5 months ago

clairesmoldychips liked this · 5 months ago

Emma. 27. A blog for Classic Literature, language learning, flowers, and aesthetic

117 posts