Comet PanSTARRS

Comet PanSTARRS

Gorgeous picture of Comet PanSTARRS taken by Carl Gruber on March 2, 2013 at a mountain lookout in Melbourne.

More Posts from Astrotidbits-blog and Others

Will Jupiter’s Great Red Spot turn into a wee red dot? by BOB KING

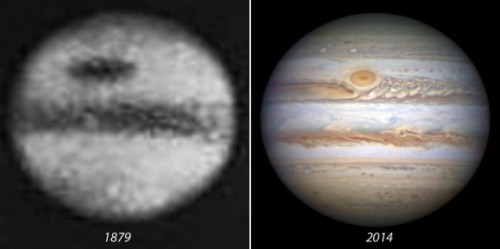

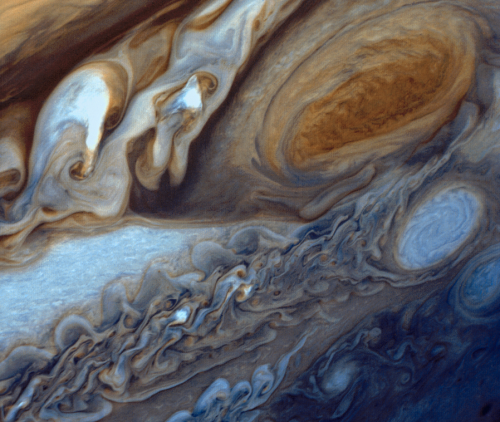

Watch out! One day it may just go away. Jupiter’s most celebrated atmospheric beauty mark, the Great Red Spot (GRS), has been shrinking for years. When I was a kid in the ’60s peering through my Edmund 6-inch reflector, not only was the Spot decidedly red, but it was extremely easy to see. Back then it really did span three Earths. Not anymore.

In the 1880s the GRS resembled a huge blimp gliding high above white crystalline clouds of ammonia and spanned 40,000 km (25, 000 miles) across. You couldn’t miss it even in those small brass refractors that were the standard amateur observing gear back in the day. Nearly one hundred years later in 1979, the Spot’s north-south extent has remained virtually unchanged, but it’s girth had shrunk to 25,000 km (15,535 miles) or just shy of two Earth diameters. Recent work done by expert astrophotographer Damian Peach using the WINJUPOS program to precisely measure the GRS in high resolution photos over the past 10 years indicates a continued steady shrinkage:

2003 Feb – 18,420km (11,445 miles)

2005 Apr – 18,000km (11,184)

2010 Sep – 17,624km (10,951)

2013 Jan – 16,954km (10,534)

2013 Sep – 15,894km (9,876)

2013 Dec – 15,302km (9,508) = 1.2 Earth diameters

If these figures stand up to professional scrutiny, it make one wonder how long the spot will continue to be a planetary highlight. It also helps explain why it’s become rather difficult to see in smaller telescopes in recent years. Yes, it’s been paler than normal and that’s played a big part, but combine pallor with a hundred-plus years of downsizing and it’s no wonder beginning amateur astronomers often struggle to locate the Spot in smaller telescopes. This observing season the Spot has developed a more pronounced red color, but unless you know what to look for, you may miss it entirely unless the local atmospheric seeing is excellent.

Not only has the Spot been shrinking, its rotation period has been speeding up. Older references give the period of one rotation at 6 days. John Rogers (British Astronomical Assn.) published a 2012 paper on the evolution of the GRS and discovered that between 2006 to 2012 – the same time as the Spot has been steadily shrinking – its rotation period has spun up to 4 days. As it shrinks, the storm appears to be conserving angular momentum by spinning faster the same way an ice skater spins up when she pulls in her arms.

Rogers also estimated a max wind speed of 300 mph, up from about 250 mph in 2006. Despite its smaller girth, this Jovian hurricane’s winds pack more punch than ever. Even more fascinating, the Great Red Spot may have even disappeared altogether from 1713 to 1830 before reappearing in 1831 as a long, pale “hollow”. According to Rogers, no observations or sketches of that era mention it. Surely something so prominent wouldn’t be missed. This begs the question of what happened in 1831. Was the “hollow” the genesis of a brand new Red Spot unrelated to the one first seen by astronomer Giovanni Cassini in 1665? Or was it the resurgence of Cassini’s Spot?

Clearly, the GRS waxes and wanes but exactly what makes it persist? By all accounts, it should have dissipated after just a few decades in Jupiter’s turbulent environment, but a new model developed by Pedram Hassanzadeh, a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University, and Philip Marcus, a professor of fluid dynamics at the University of California-Berkeley, may help to explain its longevity. At least three factors appear to be at play:

* Jupiter has no land masses. Once a large storm forms, it can sustain itself for much longer than a hurricane on Earth, which plays itself out soon after making landfall.

* Eat or be eaten: A large vortex or whirlpool like the GRS can merge with and absorb energy from numerous smaller vortices carried along by the jet streams.

* In the Hassanzadeh and Marcus model, as the storm loses energy, it’s rejuvenated by vertical winds that transport hot and cold gases in and out of the Spot, restoring its energy. Their model also predicts radial or converging winds within the Spot that suck air from neighboring jet streams toward its center. The energy gained sustains the GRS.

If the shrinkage continues, “Great” may soon have to be dropped from the Red Spot’s title. In the meantime, Oval BA (nicknamed Red Spot Jr.) and about half the size of the GRS, waits in the wings. Located along the edge of the South Temperate Belt on the opposite side of the planet from the GRS, Oval BA formed from the merger of three smaller white ovals between 1998 and 2000. Will it give the hallowed storm a run for its money? We’ll be watching.

At left, photo of Jupiter’s enormous Great Red Spot in 1879 from Agnes Clerk’s Book ” A History of Astronomy in the 19th Century”. At right, Jupiter on Jan. 10, 2014. Credit: Damian Peach

Saturn in Infrared from Cassini

The first Space Launch System hardware from NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans just arrived at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. We take a minute to introduce you to the crew of NASA’s barge Pegasus. The crew made an 18-day journey on the barge leaving New Orleans on April 28 and arriving at Marshall on May 15. The barge delivered a structural test version of the core stage engine section of SLS, NASA’s new heavy-lift rocket. Pegasus will deliver four test articles of the rocket’s core stage to Marshall for tests that will simulate the forces experienced during launch. Pegasus will later ferry the flight-ready core stage to NASA’s Stennis Space Center near Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, for testing and then to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida for integration of the SLS flight vehicle in the Vehicle Assembly Building.

Possible 360° camera drone by Samsung?

This artist’s rendering shows NASA’s Cassini spacecraft above Saturn’s northern hemisphere, heading toward its first dive between Saturn and its rings on April 26, 2017.

Jupiter’s swirling clouds around the Great Red Spot. NASA/JPL.

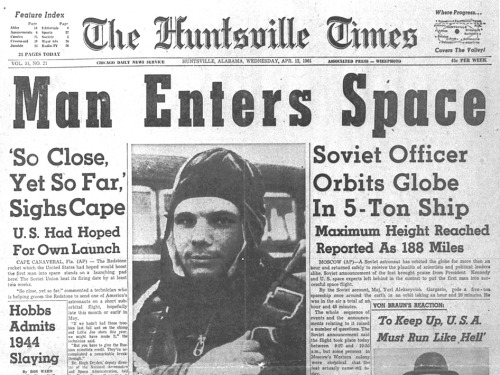

April 12th 1961: Yuri Gagarin becomes the first man in space

On this day in 1961, the Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to travel into outer space. Gagarin, a fighter pilot, was the successful candidate for the mission, being selected by Russian space programme director Sergei Korolev. Russia already had a lead in the Space Race, having launched Sputnik 1 in 1957, which was the first satellite in space. On April 12th 1961, Gagarin left Earth aboard the Vostok 1 spacecraft, famously declaring ‘Poyekhali!’ (which means ‘Let’s go!’ in Russian). He spent 108 minutes completing an orbit of the planet. Upon re-entering the atmosphere, Gagarin executed a successful ejection and landed by parachute in rural Russia, to the consternation of locals. Yuri Gagarin became famous worldwide and a Russian hero, being awarded the nation’s highest honour - Hero of the Soviet Union. Gagarin died in 1968 when the training plane he was piloting crashed; his ashes were buried in the walls of the Kremlin.

“Don’t be afraid, I am a Soviet citizen like you, who has descended from space and I must find a telephone to call Moscow!” - Gagarin to some stunned farmers when he landed

-

astrotidbits-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago

astrotidbits-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago -

astrotidbits-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago

astrotidbits-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago -

astrotidbits-blog liked this · 8 years ago

astrotidbits-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

lovely-outrage-blog reblogged this · 9 years ago

lovely-outrage-blog reblogged this · 9 years ago -

thatstupidgirll liked this · 10 years ago

thatstupidgirll liked this · 10 years ago -

rosepeace liked this · 10 years ago

rosepeace liked this · 10 years ago -

assassinborn reblogged this · 10 years ago

assassinborn reblogged this · 10 years ago -

myst-sbtrkt reblogged this · 10 years ago

myst-sbtrkt reblogged this · 10 years ago -

8cht reblogged this · 10 years ago

8cht reblogged this · 10 years ago -

inspire-nao-pire reblogged this · 10 years ago

inspire-nao-pire reblogged this · 10 years ago -

waterlem0n reblogged this · 10 years ago

waterlem0n reblogged this · 10 years ago -

waterlem0n liked this · 10 years ago

waterlem0n liked this · 10 years ago -

ehyowarrenzy reblogged this · 10 years ago

ehyowarrenzy reblogged this · 10 years ago -

cvnfused reblogged this · 10 years ago

cvnfused reblogged this · 10 years ago -

onelasttimeuntothefray liked this · 10 years ago

onelasttimeuntothefray liked this · 10 years ago -

petalpots reblogged this · 10 years ago

petalpots reblogged this · 10 years ago -

milkshakeyo reblogged this · 10 years ago

milkshakeyo reblogged this · 10 years ago -

milkshakeyo liked this · 10 years ago

milkshakeyo liked this · 10 years ago -

shootingstarsandfadingdreams liked this · 10 years ago

shootingstarsandfadingdreams liked this · 10 years ago -

iknowyourheartisfull reblogged this · 10 years ago

iknowyourheartisfull reblogged this · 10 years ago -

8cht liked this · 10 years ago

8cht liked this · 10 years ago -

everuniquelymine liked this · 10 years ago

everuniquelymine liked this · 10 years ago -

you-can-be-superhero reblogged this · 10 years ago

you-can-be-superhero reblogged this · 10 years ago -

frxgilelittleflxme reblogged this · 10 years ago

frxgilelittleflxme reblogged this · 10 years ago -

silent-in-the-trees reblogged this · 10 years ago

silent-in-the-trees reblogged this · 10 years ago -

shialou liked this · 10 years ago

shialou liked this · 10 years ago -

fettaa reblogged this · 10 years ago

fettaa reblogged this · 10 years ago -

chikns96 reblogged this · 10 years ago

chikns96 reblogged this · 10 years ago -

valosaaste reblogged this · 10 years ago

valosaaste reblogged this · 10 years ago -

wintersleepsandrosycheeks reblogged this · 10 years ago

wintersleepsandrosycheeks reblogged this · 10 years ago -

myst-sbtrkt liked this · 10 years ago

myst-sbtrkt liked this · 10 years ago -

echelon-wolffie reblogged this · 10 years ago

echelon-wolffie reblogged this · 10 years ago -

devils---daughter reblogged this · 10 years ago

devils---daughter reblogged this · 10 years ago -

t-r-0-u-b-l-e-m-4-k-e-r reblogged this · 10 years ago

t-r-0-u-b-l-e-m-4-k-e-r reblogged this · 10 years ago -

t-r-0-u-b-l-e-m-4-k-e-r liked this · 10 years ago

t-r-0-u-b-l-e-m-4-k-e-r liked this · 10 years ago -

no-im-not-an-otaku reblogged this · 10 years ago

no-im-not-an-otaku reblogged this · 10 years ago -

ace reblogged this · 10 years ago

ace reblogged this · 10 years ago -

gigibrown1 liked this · 10 years ago

gigibrown1 liked this · 10 years ago