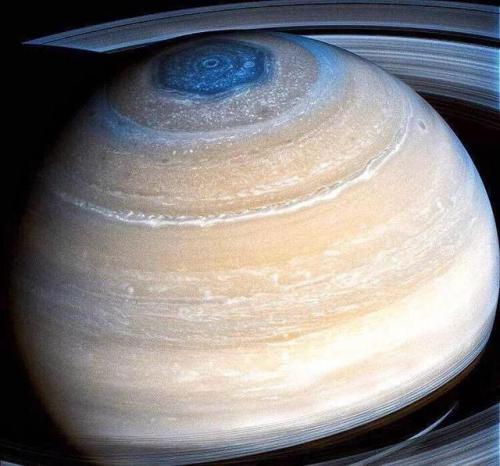

Clearest Image Ever Taken Of Saturn.

Clearest image ever taken of Saturn.

More Posts from Ziranjie and Others

Captured here in this picturesque photo, mountain peaks in northern Italy poke through Earth’s water clouds and come between them and the Milky Way’s star clouds. High above the mountains, and far in the distance, dark dust lanes streak out from the central plane of our Milky Way Galaxy. The stars and dust are dotted with bright red clouds of glowing hydrogen gas, such as the Lagoon Nebula just above and to the left of center.

Image Credit & Copyright: Angelo Perrone

“Rumors of a Dark Universe ” Is the NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day of today, August 04, 2019

Cassini Mission: What’s Next?

It’s Friday, Sept. 15 and our Cassini mission has officially come to a spectacular end. The final signal from the spacecraft was received here on Earth at 7:55 a.m. EDT after a fateful plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere.

After losing contact with Earth, the spacecraft burned up like a meteor, becoming part of the planet itself.

Although bittersweet, Cassini’s triumphant end is the culmination of a nearly 20-year mission that overflowed with discoveries.

But, what happens now?

Mission Team and Data

Now that the spacecraft is gone, most of the team’s engineers are migrating to other planetary missions, where they will continue to contribute to the work we’re doing to explore our solar system and beyond.

Mission scientists will keep working for the coming years to ensure that we fully understand all of the data acquired during the mission’s Grand Finale. They will carefully calibrate and study all of this data so that it can be entered into the Planetary Data System. From there, it will be accessible to future scientists for years to come.

Even beyond that, the science data will continue to be worked on for decades, possibly more, depending on the research grants that are acquired.

Other team members, some who have spent most of their career working on the Cassini mission, will use this as an opportunity to retire.

Future Missions

In revealing that Enceladus has essentially all the ingredients needed for life, the mission energized a pivot to the exploration of “ocean worlds” that has been sweeping planetary science over the past couple of decades.

Jupiter’s moon Europa has been a prime target for future exploration, and many lessons during Cassini’s mission are being applied in planning our Europa Clipper mission, planned for launch in the 2020s.

The mission will orbit the giant planet, Jupiter, using gravitational assists from large moons to maneuver the spacecraft into repeated close encounters, much as Cassini has used the gravity of Titan to continually shape the spacecraft’s course.

In addition, many engineers and scientists from Cassini are serving on the new Europa Clipper mission and helping to shape its science investigations. For example, several members of the Cassini Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer team are developing an extremely sensitive, next-generation version of their instrument for flight on Europa Clipper. What Cassini has learned about flying through the plume of material spraying from Enceladus will be invaluable to Europa Clipper, should plume activity be confirmed on Europa.

In the decades following Cassini, scientists hope to return to the Saturn system to follow up on the mission’s many discoveries. Mission concepts under consideration include robotic explorers to drift on the methane seas of Titan and fly through the Enceladus plume to collect and analyze samples for signs of biology.

Atmospheric probes to all four of the outer planets have long been a priority for the science community, and the most recent recommendations from a group of planetary scientists shows interest in sending such a mission to Saturn. By directly sampling Saturn’s upper atmosphere during its last orbits and final plunge, Cassini is laying the groundwork for an potential Saturn atmospheric probe.

A variety of potential mission concepts are discussed in a recently completed study — including orbiters, flybys and probes that would dive into Uranus’ atmosphere to study its composition. Future missions to the ice giants might explore those worlds using an approach similar to Cassini’s mission.

Learn more about the Cassini mission and its Grand Finale HERE.

Follow the mission on Facebook and Twitter for the latest updates.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

This Week in Science History: Launch of the Hubble Telescope

On April 24, 1990, the Hubble telescope was launched into orbit aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery. The telescope carried five instruments: The Wide Field/Planetary Camera, the Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph, the Faint Object Camera, the Faint Object Spectrograph and the High Speed Photometer. The Hubble is a telescope that orbits Earth and is positioned above the atmosphere. This position distorts and blocks the light that reaches Earth and gives a view of the universe that typically surpasses the view of a ground-based telescope. The Hubble Telescope revealed the age of the universe to be about 13 to 14 billion years, giving a more accurate range than the previous range of between 10 to 20 billion years. In addition, the Hubble Telescope had a key role in the discovery of dark energy. The telescope has captured galaxies in all stages of evolution, most prominently toddler galaxies that were around when the universe was still young. This has helped scientists in understanding how galaxies form. It found protoplanetary disks (clumps of gas and dust around young stars, likely function as birthing grounds for new planets) and gamma-ray bursts. More than 10,000 scientific articles have been published based on Hubble data.

Read more at: http://hubblesite.org/the_telescope/hubble_essentials/

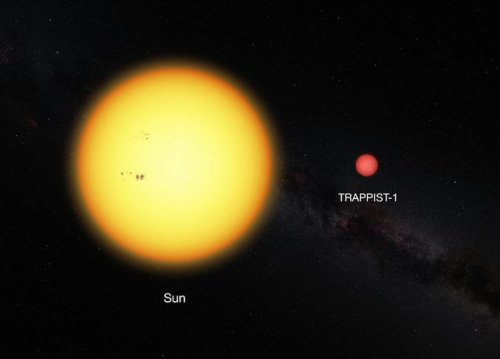

Hubble delivers first hints of possible water content of TRAPPIST-1 planets

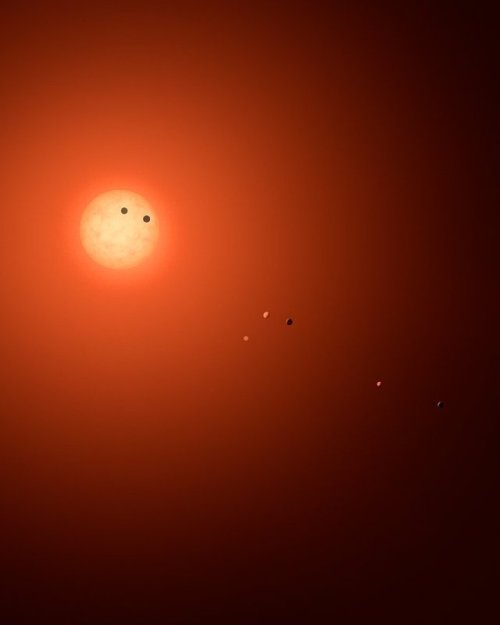

On 22 February 2017 astronomers announced the discovery of seven Earth-sized planets orbiting the ultracool dwarf star TRAPPIST-1, 40 light-years away. This makes TRAPPIST-1 the planetary system with the largest number of Earth-sized planets discovered so far.

Following up on the discovery, an international team of scientists led by the Swiss astronomer Vincent Bourrier from the Observatoire de l’Université de Genève, used the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) on the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope to study the amount of ultraviolet radiation received by the individual planets of the system. “Ultraviolet radiation is an important factor in the atmospheric evolution of planets,” explains Bourrier. “As in our own atmosphere, where ultraviolet sunlight breaks molecules apart, ultraviolet starlight can break water vapour in the atmospheres of exoplanets into hydrogen and oxygen.”

While lower-energy ultraviolet radiation breaks up water molecules — a process called photodissociation — ultraviolet rays with more energy (XUV radiation) and X-rays heat the upper atmosphere of a planet, which allows the products of photodissociation, hydrogen and oxygen, to escape.

As it is very light, hydrogen gas can escape the exoplanets’ atmospheres and be detected around the exoplanets with Hubble, acting as a possible indicator of atmospheric water vapour. The observed amount of ultraviolet radiation emitted by TRAPPIST-1 indeed suggests that the planets could have lost gigantic amounts of water over the course of their history.

This is especially true for the innermost two planets of the system, TRAPPIST-1b and TRAPPIST-1c, which receive the largest amount of ultraviolet energy. “Our results indicate that atmospheric escape may play an important role in the evolution of these planets,” summarises Julien de Wit, from MIT, USA, co-author of the study.

The inner planets could have lost more than 20 Earth-oceans-worth of water during the last eight billion years. However, the outer planets of the system — including the planets e, f and g which are in the habitable zone — should have lost much less water, suggesting that they could have retained some on their surfaces. The calculated water loss rates as well as geophysical water release rates also favour the idea that the outermost, more massive planets retain their water. However, with the currently available data and telescopes no final conclusion can be drawn on the water content of the planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1.

“While our results suggest that the outer planets are the best candidates to search for water with the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, they also highlight the need for theoretical studies and complementary observations at all wavelengths to determine the nature of the TRAPPIST-1 planets and their potential habitability,” concludes Bourrier.

To see the animation of the seven planets of the trappist-1 system, click here!

Source: spacetelescope.org & Image credit: eso.org

From the unique vantage point of about 25,000 feet above Earth, our Associate Administrator of Science at NASA, Dr. Thomas Zurbuchen, witnessed the 2017 eclipse. He posted this video to his social media accounts saying, “At the speed of darkness…watch as #SolarEclipse2017 shadow moves across our beautiful planet at <1 mile/second; as seen from GIII aircraft”.

Zurbuchen, along with NASA Acting Administrator Robert Lightfoot, Associate Administrator Lesa Roe traveled on a specially modified Gulfstream III aircraft flying north over the skies of Oregon.

In order to capture images of the event, the standard windows of the Gulfstream III were replaced with optical glass providing a clear view of the eclipse. This special glass limits glare and distortion of common acrylic aircraft windows. Heaters are aimed at the windows where the imagery equipment will be used to prevent icing that could obscure a clear view of the eclipse.

Learn more about the observations of the eclipse made from this aircraft HERE.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Europa and Jupiter from Voyager 1: Alexis Tranchandon / Solaris

Why Bennu? 10 Reasons

After traveling for two years and billions of kilometers from Earth, the OSIRIS-REx probe is only a few months away from its destination: the intriguing asteroid Bennu. When it arrives in December, OSIRIS-REx will embark on a nearly two-year investigation of this clump of rock, mapping its terrain and finding a safe and fruitful site from which to collect a sample.

The spacecraft will briefly touch Bennu’s surface around July 2020 to collect at least 60 grams (equal to about 30 sugar packets) of dirt and rocks. It might collect as much as 2,000 grams, which would be the largest sample by far gathered from a space object since the Apollo Moon landings. The spacecraft will then pack the sample into a capsule and travel back to Earth, dropping the capsule into Utah’s west desert in 2023, where scientists will be waiting to collect it.

This years-long quest for knowledge thrusts Bennu into the center of one of the most ambitious space missions ever attempted. But the humble rock is but one of about 780,000 known asteroids in our solar system. So why did scientists pick Bennu for this momentous investigation? Here are 10 reasons:

1. It’s close to Earth

Unlike most other asteroids that circle the Sun in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, Bennu’s orbit is close in proximity to Earth’s, even crossing it. The asteroid makes its closest approach to Earth every 6 years. It also circles the Sun nearly in the same plane as Earth, which made it somewhat easier to achieve the high-energy task of launching the spacecraft out of Earth’s plane and into Bennu’s. Still, the launch required considerable power, so OSIRIS-REx used Earth’s gravity to boost itself into Bennu’s orbital plane when it passed our planet in September 2017.

2. It’s the right size

Asteroids spin on their axes just like Earth does. Small ones, with diameters of 200 meters or less, often spin very fast, up to a few revolutions per minute. This rapid spinning makes it difficult for a spacecraft to match an asteroid’s velocity in order to touch down and collect samples. Even worse, the quick spinning has flung loose rocks and soil, material known as “regolith” — the stuff OSIRIS-REx is looking to collect — off the surfaces of small asteroids. Bennu’s size, in contrast, makes it approachable and rich in regolith. It has a diameter of 492 meters, which is a bit larger than the height of the Empire State Building in New York City, and rotating once every 4.3 hours.

3. It’s really old

Bennu is a leftover fragment from the tumultuous formation of the solar system. Some of the mineral fragments inside Bennu could be older than the solar system. These microscopic grains of dust could be the same ones that spewed from dying stars and eventually coalesced to make the Sun and its planets nearly 4.6 billion years ago. But pieces of asteroids, called meteorites, have been falling to Earth’s surface since the planet formed. So why don’t scientists just study those old space rocks? Because astronomers can’t tell (with very few exceptions) what kind of objects these meteorites came from, which is important context. Furthermore, these stones, that survive the violent, fiery decent to our planet’s surface, get contaminated when they land in the dirt, sand, or snow. Some even get hammered by the elements, like rain and snow, for hundreds or thousands of years. Such events change the chemistry of meteorites, obscuring their ancient records.

4. It’s well preserved

Bennu, on the other hand, is a time capsule from the early solar system, having been preserved in the vacuum of space. Although scientists think it broke off a larger asteroid in the asteroid belt in a catastrophic collision between about 1 and 2 billion years ago, and hurtled through space until it got locked into an orbit near Earth’s, they don’t expect that these events significantly altered it.

5. It might contain clues to the origin of life

Analyzing a sample from Bennu will help planetary scientists better understand the role asteroids may have played in delivering life-forming compounds to Earth. We know from having studied Bennu through Earth- and space-based telescopes that it is a carbonaceous, or carbon-rich, asteroid. Carbon is the hinge upon which organic molecules hang. Bennu is likely rich in organic molecules, which are made of chains of carbon bonded with atoms of oxygen, hydrogen, and other elements in a chemical recipe that makes all known living things. Besides carbon, Bennu also might have another component important to life: water, which is trapped in the minerals that make up the asteroid.

6. It contains valuable materials

Besides teaching us about our cosmic past, exploring Bennu close-up will help humans plan for the future. Asteroids are rich in natural resources, such as iron and aluminum, and precious metals, such as platinum. For this reason, some companies, and even countries, are building technologies that will one day allow us to extract those materials. More importantly, asteroids like Bennu are key to future, deep-space travel. If humans can learn how to extract the abundant hydrogen and oxygen from the water locked up in an asteroid’s minerals, they could make rocket fuel. Thus, asteroids could one day serve as fuel stations for robotic or human missions to Mars and beyond. Learning how to maneuver around an object like Bennu, and about its chemical and physical properties, will help future prospectors.

7. It will help us better understand other asteroids

Astronomers have studied Bennu from Earth since it was discovered in 1999. As a result, they think they know a lot about the asteroid’s physical and chemical properties. Their knowledge is based not only on looking at the asteroid, but also studying meteorites found on Earth, and filling in gaps in observable knowledge with predictions derived from theoretical models. Thanks to the detailed information that will be gleaned from OSIRIS-REx, scientists now will be able to check whether their predictions about Bennu are correct. This work will help verify or refine telescopic observations and models that attempt to reveal the nature of other asteroids in our solar system.

8. It will help us better understand a quirky solar force …

Astronomers have calculated that Bennu’s orbit has drifted about 280 meters (0.18 miles) per year toward the Sun since it was discovered. This could be because of a phenomenon called the Yarkovsky effect, a process whereby sunlight warms one side of a small, dark asteroid and then radiates as heat off the asteroid as it rotates. The heat energy thrusts an asteroid either away from the Sun, if it has a prograde spin like Earth, which means it spins in the same direction as its orbit, or toward the Sun in the case of Bennu, which spins in the opposite direction of its orbit. OSIRIS-REx will measure the Yarkovsky effect from close-up to help scientists predict the movement of Bennu and other asteroids. Already, measurements of how this force impacted Bennu over time have revealed that it likely pushed it to our corner of the solar system from the asteroid belt.

9. … and to keep asteroids at bay

One reason scientists are eager to predict the directions asteroids are drifting is to know when they’re coming too-close-for-comfort to Earth. By taking the Yarkovsky effect into account, they’ve estimated that Bennu could pass closer to Earth than the Moon is in 2135, and possibly even closer between 2175 and 2195. Although Bennu is unlikely to hit Earth at that time, our descendants can use the data from OSIRIS-REx to determine how best to deflect any threatening asteroids that are found, perhaps even by using the Yarkovsky effect to their advantage.

10. It’s a gift that will keep on giving

Samples of Bennu will return to Earth on September 24, 2023. OSIRIS-REx scientists will study a quarter of the regolith. The rest will be made available to scientists around the globe, and also saved for those not yet born, using techniques not yet invented, to answer questions not yet asked.

Read the web version of this week’s “Solar System: 10 Things to Know” article HERE.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

-

fohatic liked this · 1 year ago

fohatic liked this · 1 year ago -

mor-and-more reblogged this · 2 years ago

mor-and-more reblogged this · 2 years ago -

dirtypiper liked this · 3 years ago

dirtypiper liked this · 3 years ago -

the-organizing-principle liked this · 5 years ago

the-organizing-principle liked this · 5 years ago -

allxfoo reblogged this · 5 years ago

allxfoo reblogged this · 5 years ago -

virginidad-perdida reblogged this · 5 years ago

virginidad-perdida reblogged this · 5 years ago -

virginidad-perdida liked this · 5 years ago

virginidad-perdida liked this · 5 years ago -

horrificallysweet liked this · 5 years ago

horrificallysweet liked this · 5 years ago -

trippyskippy reblogged this · 5 years ago

trippyskippy reblogged this · 5 years ago -

goodgoodgod reblogged this · 5 years ago

goodgoodgod reblogged this · 5 years ago -

kannaenndo reblogged this · 5 years ago

kannaenndo reblogged this · 5 years ago -

wickedgameswastedtimes liked this · 5 years ago

wickedgameswastedtimes liked this · 5 years ago -

shacotte liked this · 5 years ago

shacotte liked this · 5 years ago -

garfieldslastlasagna reblogged this · 5 years ago

garfieldslastlasagna reblogged this · 5 years ago -

sw4mpwitch liked this · 5 years ago

sw4mpwitch liked this · 5 years ago -

cicekleniyorum liked this · 5 years ago

cicekleniyorum liked this · 5 years ago -

johanrapper reblogged this · 5 years ago

johanrapper reblogged this · 5 years ago -

zenobriaa reblogged this · 5 years ago

zenobriaa reblogged this · 5 years ago -

barkingforbrooks reblogged this · 5 years ago

barkingforbrooks reblogged this · 5 years ago -

barkingforbrooks liked this · 5 years ago

barkingforbrooks liked this · 5 years ago -

tiderust reblogged this · 5 years ago

tiderust reblogged this · 5 years ago -

tiderust liked this · 5 years ago

tiderust liked this · 5 years ago -

rywen reblogged this · 5 years ago

rywen reblogged this · 5 years ago