“The Best Preparation For Tomorrow Is Doing Your Best Today.”

“The best preparation for tomorrow is doing your best today.”

— H. Jackson Brown

More Posts from Thehkr and Others

It takes strength and courage to admit the truth.

Rick Riordan (via quotemadness)

On Top of The World – Literally

What’s one perk about applying to #BeAnAstronaut? You’re one step closer to being on top of the world.

Part of the job of a NASA astronaut is a task called spacewalking. Spacewalking refers to any time an astronaut gets out of a vehicle while in space; it is performed for many reasons such as completing repairs outside the International Space Station, conducting science experiments and testing new equipment.

Spacewalking can last anywhere from five to eight hours, and for that reason, astronauts’ spacesuits are more like mini-spacecraft than uniforms! Inside spacesuits, astronauts have the oxygen they need to breathe, water to drink and a bathroom!

Spacesuits also protect astronauts from the extreme environment of space. In Earth orbit, conditions can be as cold as minus 250 degrees Fahrenheit. In the sunlight, they can be as hot as 250 degrees. A spacesuit protects astronauts from those extreme temperatures.

To stay safe during spacewalks, astronauts are tethered to the International Space Station. The tethers, like ropes, are hooked to the astronaut and the space station – ensuring the astronaut does not float away into space.

Spacewalking can be a demanding task. Astronauts can burn anywhere from ~1500-2500 calories during one full assignment. That’s about equal to running 2/3 of a marathon.

Does spacewalking sound like something you’d be interested in? If so, you might want to APPLY to #BeAnAstronaut! Applications are open until March 31. Don’t miss your chance to!

Want to learn more about what it takes to be an astronaut? Or, maybe you just want more epic images. Either way, check out nasa.gov/astronauts for all your NASA astronaut needs!

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

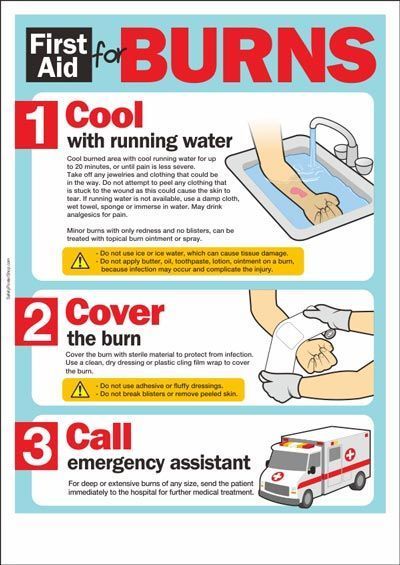

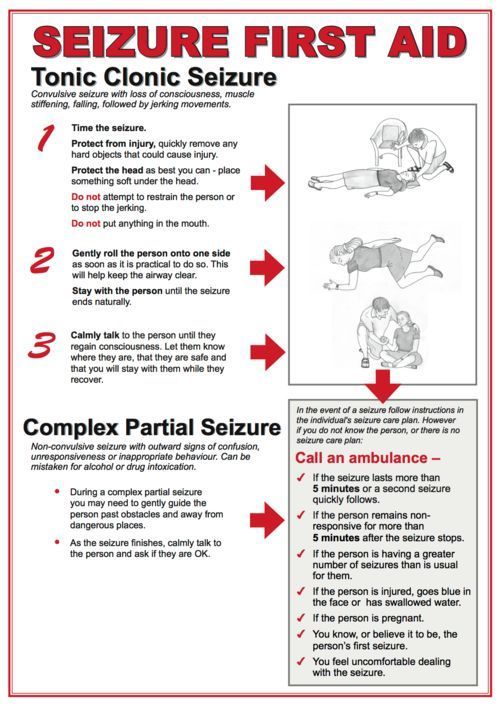

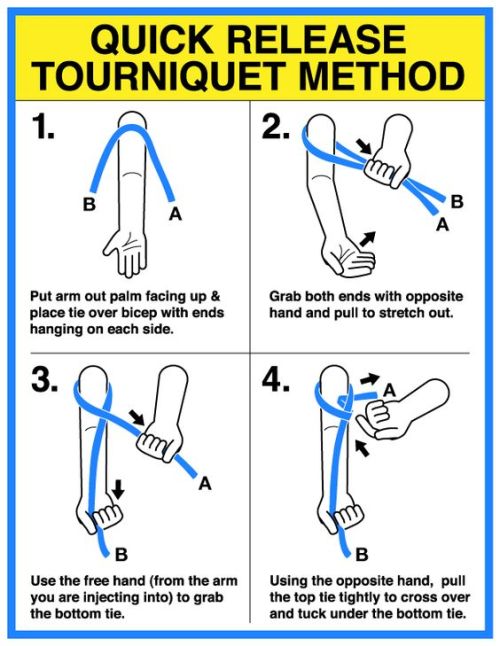

Survival Skills

Kung Fu feiyue shoes on: http://www.icnbuys.com/feiyue-shoes.

Roman's primary structure hangs from cables as it moves into the big clean room at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

What Makes the Clean Room So Clean?

When you picture NASA’s most important creations, you probably think of a satellite, telescope, or maybe a rover. But what about the room they’re made in? Believe it or not, the room itself where these instruments are put together—a clean room—is pretty special.

A clean room is a space that protects technology from contamination. This is especially important when sending very sensitive items into space that even small particles could interfere with.

There are two main categories of contamination that we have to keep away from our instruments. The first is particulate contamination, like dust. The second is molecular contamination, which is more like oil or grease. Both types affect a telescope’s image quality, as well as the time it takes to capture imagery. Having too many particles on our instruments is like looking through a dirty window. A clean room makes for clean science!

Two technicians clean the floor of Goddard’s big clean room.

Our Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland has the largest clean room of its kind in the world. It’s as tall as an eight-story building and as wide as two basketball courts.

Goddard’s clean room has fewer than 3,000 micron-size particles per cubic meter of air. If you lined up all those tiny particles, they’d be no longer than a sesame seed. If those particles were the size of 16-inch (0.4-meter) inflatable beach balls, we’d find only 3,000 spread throughout the whole body of Mount Everest!

A clean room technician observes a sample under a microscope.

The clean room keeps out particles larger than five microns across, just seven percent of the width of an average human hair. It does this via special filters that remove around 99.97% of particles 0.3 microns and larger from incoming air. Six fans the size of school buses spin to keep air flowing and pressurize the room. Since the pressure inside is higher, the clean air keeps unclean air out when doors open.

A technician analyzes a sample under ultraviolet light.

In addition, anyone who enters must wear a “bunny suit” to keep their body particles away from the machinery. A bunny suit covers most of the person inside. Sometimes scientists have trouble recognizing each other while in the suits, but they do get to know each other’s mannerisms very well.

This illustration depicts the anatomy of a bunny suit, which covers clean room technicians from head to toe to protect sensitive technology.

The bunny suit is only the beginning: before putting it on, team members undergo a preparation routine involving a hairnet and an air shower. Fun fact – you’re not allowed to wear products like perfume, lotion, or deodorant. Even odors can transfer easily!

Six of Goddard’s clean room technicians (left to right: Daniel DaCosta, Jill Bender, Anne Martino, Leon Bailey, Frank D’Annunzio, and Josh Thomas).

It takes a lot of specialists to run Goddard’s clean room. There are 10 people on the Contamination Control Technician Team, 30 people on the Clean Room Engineering Team to cover all Goddard missions, and another 10 people on the Facilities Team to monitor the clean room itself. They check on its temperature, humidity, and particle counts.

A technician rinses critical hardware with isopropyl alcohol and separates the particulate and isopropyl alcohol to leave the particles on a membrane for microscopic analysis.

Besides the standard mopping and vacuuming, the team uses tools such as isopropyl alcohol, acetone, wipes, swabs, white light, and ultraviolet light. Plus, they have a particle monitor that uses a laser to measure air particle count and size.

The team keeping the clean room spotless plays an integral role in the success of NASA’s missions. So, the next time you have to clean your bedroom, consider yourself lucky that the stakes aren’t so high!

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

The Rover Doctor is in: The Anatomy of a NASA Human Exploration Rover Challenge Rover

Exploration and inspiration collide head-on in our Human Exploration Rover Challenge held near Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, each April. The annual competition challenges student teams from around the world to design, build and drive a human-powered rover over a punishing half-mile course with tasks and obstacles similar to what our astronauts will likely have on missions to the Moon, Mars and beyond.

The anatomy of the rover is crucial to success. Take a look at a few of the vital systems your rover will need to survive the challenge!

The Chassis

A rover’s chassis is its skeleton and serves as the framework that all of the other rover systems attach to. The design of that skeleton incorporates many factors: How will your steering and braking work? Will your drivers sit beside each other, front-to-back or will they be offset? How high should they sit? How many wheels will your rover have? All of those decisions dictate the design of your rover’s chassis.

Wheels

Speaking of wheels, what will yours look like? The Rover Challenge course features slick surfaces, soft dunes, rocky craters and steep hills – meaning your custom-designed wheels must be capable of handling diverse landscapes, just as they would on the Moon and Mars. Carefully cut wood and cardboard, hammer-formed metal and even 3-D printed polymers have all traversed the course in past competitions.

Drivetrain

You’ve got your chassis design. Your wheels are good to go. Now you have to have a system to transfer the energy from your drivers to the wheels – the drivetrain. A good drivetrain will help ensure your rover crosses the finish line under the 8-minute time limit. Teams are encouraged to innovate and think outside the traditional bike chain-based systems that are often used and often fail. Exploration of the Moon and Mars will require new, robust designs to explore their surfaces. New ratchet systems and geared drivetrains explored the Rover Challenge course in 2019.

Colors and Gear

Every good rover needs a cool look. Whether you paint it your school colors, fly your country’s flag or decorate it to support those fighting cancer (Lima High School, above, was inspired by those fighting cancer), your rover and your uniform help tell your story to all those watching and cheering you on. Have fun with it!

Are you ready to conquer the Rover Challenge course? Join us in Huntsville this spring! Rover Challenge registration is open until January 16, 2020 for teams based in the United States.

If building rovers isn’t your space jam, we have other Artemis Challenges that allow you to be a part of the NASA team – check them out here.

Want to learn about our Artemis program that will land the first woman and next man on the Moon by 2024? Go here to read about how NASA, academia and industry and international partners will use innovative technologies to explore more of the lunar surface than ever before. Through collaborations with our commercial, international and academic partners, we will establish sustainable lunar exploration by 2028, using what we learn to take astronauts to Mars.

The students competing in our Human Exploration Rover Challenge are paramount to that exploration and will play a vital role in helping NASA and all of humanity explore space like we’ve never done before!

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Dark Energy

This bone-chilling force will leave you shivering alone in terror! An unseen power is prowling throughout the cosmos, driving the universe to expand at a quickening rate. This relentless pressure, called dark energy, is nothing like dark matter, that mysterious material revealed only by its gravitational pull. Dark energy offers a bigger fright: pushing galaxies farther apart over trillions of years, leaving the universe to an inescapable, freezing death in the pitch black expanse of outer space. Download this free poster in English and Spanish and check out the full Galaxy of Horrors.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

Throwback Thursday: Frequently Asked Questions about Apollo

In celebration of the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11, we’ll be sharing answers to some frequently asked questions about the first time humans voyaged to the Moon. Answers have been compiled from archivists in the NASA History Office.

How many people worked on the Apollo program?

At the height of Apollo in 1965, about 409,900 people worked on some aspect of the program, but that number doesn’t capture it all.

It doesn’t represent the people who worked on mission concepts or spacecraft design, such as the engineers who did the wind tunnel testing of the Apollo Command Module and then moved on to other projects. The number also doesn’t represent the NASA astronauts, mission controllers, remote communications personnel, etc. who would have transferred to the Apollo program only after the end of Gemini program (1966-1967). There were still others who worked on the program only part-time or served on temporary committees. In the image above are three technicians studying an Apollo 14 Moon rock in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory at Johnson Space Center. From left to right, they are Linda Tyler, Nancy Trent and Sandra Richards.

How many people have walked on the Moon so far?

This artwork portrait done by spaceflight historian Ed Hengeveld depicts the 12 people who have walked on the Moon so far. In all, 24 people have flown to the Moon and three of them, John Young, Jim Lovell and Gene Cernan, have made the journey twice.

But these numbers will increase.

Are the U.S. flags that were planted on the Moon still standing?

Every successful Apollo lunar landing mission left a flag on the Moon but we don’t know yet whether all are still standing. Some flags were set up very close to the Lunar Module and were in the blast radius of its ascent engine, so it’s possible that some of them could have been knocked down. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin both reported that the flag had been knocked down following their ascent.

Our Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter took photographs of all the Apollo lunar landing sites. In the case of the Apollo 17 site, you can see the shadow of the upright flag.

But why does it look like it’s waving?

The flags appear to “wave” or “flap” but actually they’re swinging. Swinging motions on Earth are dampened due to gravity and air resistance, but on the Moon any swinging motion can continue for much longer. Once the flags settled (and were clear of the ascent stage exhaust), they remained still. And how is the flag hanging? Before launching, workers on the ground had attached a horizontal rod to the top of each flag for support, allowing it to be visible in pictures and television broadcasts to the American public. Armstrong and Aldrin did not fully extend the rod once they were on the Moon, giving the flag a ripple effect. The other astronauts liked the ripple effect so much that they also did not completely extend the rod.

Why don’t we see stars in any of the pictures?

Have you ever taken a photo of the night sky with your phone or camera? You likely won’t see any stars because chances are your camera’s settings are set to short exposure time only lets it quickly take in the light off the bright objects closest to you. It’s the same reason you generally don’t see stars in spacewalk pictures from the International Space Station. There’s no use for longer exposure times to get an image like this one of Bruce McCandless in 1984 as seen Space Shuttle Challenger (STS-41B).

The Hasselblad cameras that Apollo astronauts flew with were almost always set to short exposure times. And why didn’t the astronauts photograph the stars? Well, they were busy exploring the Moon!

When are we going back to the Moon?

The first giant leap was only the beginning. Work is under way to send the first woman and the next man to the Moon in five years. As we prepare to launch the next era of exploration, the new Artemis program is the first step in humanity’s presence on the the Moon and beyond.

Keep checking back for more answers to Apollo FAQs.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

-

aclarando liked this · 5 months ago

aclarando liked this · 5 months ago -

mercymedic liked this · 1 year ago

mercymedic liked this · 1 year ago -

warriorhealer liked this · 1 year ago

warriorhealer liked this · 1 year ago -

therealgeo3 reblogged this · 1 year ago

therealgeo3 reblogged this · 1 year ago -

mercymedicarchive reblogged this · 2 years ago

mercymedicarchive reblogged this · 2 years ago -

carpe-diem-but-first-coffee liked this · 2 years ago

carpe-diem-but-first-coffee liked this · 2 years ago -

supermantm reblogged this · 2 years ago

supermantm reblogged this · 2 years ago -

desimoods reblogged this · 2 years ago

desimoods reblogged this · 2 years ago -

art-rooooom reblogged this · 2 years ago

art-rooooom reblogged this · 2 years ago -

ifnot-me liked this · 2 years ago

ifnot-me liked this · 2 years ago -

lexiouse liked this · 2 years ago

lexiouse liked this · 2 years ago -

madita16 liked this · 2 years ago

madita16 liked this · 2 years ago -

itstsmme liked this · 2 years ago

itstsmme liked this · 2 years ago -

thug-tears reblogged this · 2 years ago

thug-tears reblogged this · 2 years ago -

cinnamongirl97 reblogged this · 2 years ago

cinnamongirl97 reblogged this · 2 years ago -

blahhh11123 liked this · 2 years ago

blahhh11123 liked this · 2 years ago -

ill-go-fuck-myself-its-fine liked this · 2 years ago

ill-go-fuck-myself-its-fine liked this · 2 years ago -

chihaya-shiruru liked this · 2 years ago

chihaya-shiruru liked this · 2 years ago -

trh1213 reblogged this · 2 years ago

trh1213 reblogged this · 2 years ago -

trh1213 liked this · 2 years ago

trh1213 liked this · 2 years ago -

olly-emotes reblogged this · 2 years ago

olly-emotes reblogged this · 2 years ago -

olly-emotes liked this · 2 years ago

olly-emotes liked this · 2 years ago -

cccrrrmm reblogged this · 2 years ago

cccrrrmm reblogged this · 2 years ago -

louisnvogue liked this · 2 years ago

louisnvogue liked this · 2 years ago -

kafkassoulmate liked this · 2 years ago

kafkassoulmate liked this · 2 years ago -

mynorthernmassachusetts reblogged this · 2 years ago

mynorthernmassachusetts reblogged this · 2 years ago -

dzieckoprzygody reblogged this · 2 years ago

dzieckoprzygody reblogged this · 2 years ago -

weepingdalliance liked this · 2 years ago

weepingdalliance liked this · 2 years ago -

olkarenana liked this · 2 years ago

olkarenana liked this · 2 years ago -

chihaya-shiruru reblogged this · 2 years ago

chihaya-shiruru reblogged this · 2 years ago -

tiffanystellar liked this · 2 years ago

tiffanystellar liked this · 2 years ago -

skull-crushing liked this · 2 years ago

skull-crushing liked this · 2 years ago -

summeralive reblogged this · 2 years ago

summeralive reblogged this · 2 years ago -

devilsxcherry liked this · 2 years ago

devilsxcherry liked this · 2 years ago -

winzjenz liked this · 2 years ago

winzjenz liked this · 2 years ago -

twobloodyknees liked this · 2 years ago

twobloodyknees liked this · 2 years ago -

neverbreakthe2chainz liked this · 2 years ago

neverbreakthe2chainz liked this · 2 years ago