Solar System 10 Things: Looking Back At Pluto

Solar System 10 Things: Looking Back at Pluto

In July 2015, we saw Pluto up close for the first time and—after three years of intense study—the surprises keep coming. “It’s clear,” says Jeffery Moore, New Horizons’ geology team lead, “Pluto is one of the most amazing and complex objects in our solar system.”

1. An Improving View

These are combined observations of Pluto over the course of several decades. The first frame is a digital zoom-in on Pluto as it appeared upon its discovery by Clyde Tombaugh in 1930. More frames show of Pluto as seen by the Hubble Space Telescope. The final sequence zooms in to a close-up frame of Pluto taken by our New Horizons spacecraft on July 14, 2015.

2. The Heart

Pluto’s surface sports a remarkable range of subtle colors are enhanced in this view to a rainbow of pale blues, yellows, oranges, and deep reds. Many landforms have their own distinct colors, telling a complex geological and climatological story that scientists have only just begun to decode. The image resolves details and colors on scales as small as 0.8 miles (1.3 kilometers). Zoom in on the full resolution image on a larger screen to fully appreciate the complexity of Pluto’s surface features.

3. The Smiles

July 14, 2015: New Horizons team members Cristina Dalle Ore, Alissa Earle and Rick Binzel react to seeing the spacecraft’s last and sharpest image of Pluto before closest approach.

4. Majestic Mountains

Just 15 minutes after its closest approach to Pluto, the New Horizons spacecraft captured this near-sunset view of the rugged, icy mountains and flat ice plains extending to Pluto’s horizon. The backlighting highlights more than a dozen layers of haze in Pluto’s tenuous atmosphere. The image was taken from a distance of 11,000 miles (18,000 kilometers) to Pluto; the scene is 780 miles (1,250 kilometers) wide.

5. Icy Dunes

Found near the mountains that encircle Pluto’s Sputnik Planitia plain, newly discovered ridges appear to have formed out of particles of methane ice as small as grains of sand, arranged into dunes by wind from the nearby mountains.

6. Glacial Plains

The vast nitrogen ice plains of Pluto’s Sputnik Planitia – the western half of Pluto’s “heart”—continue to give up secrets. Scientists processed images of Sputnik Planitia to bring out intricate, never-before-seen patterns in the surface textures of these glacial plains.

7. Colorful and Violent Charon

High resolution images of Pluto’s largest moon, Charon, show a surprisingly complex and violent history. Scientists expected Charon to be a monotonous, crater-battered world; instead, they found a landscape covered with mountains, canyons, landslides, surface-color variations and more.

8. Ice Volcanoes

One of two potential cryovolcanoes spotted on the surface of Pluto by the New Horizons spacecraft. This feature, known as Wright Mons, was informally named by the New Horizons team in honor of the Wright brothers. At about 90 miles (150 kilometers) across and 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) high, this feature is enormous. If it is in fact an ice volcano, as suspected, it would be the largest such feature discovered in the outer solar system.

9. Blue Rays

Pluto’s receding crescent as seen by New Horizons at a distance of 120,000 miles (200,000 kilometers). Scientists believe the spectacular blue haze is a photochemical smog resulting from the action of sunlight on methane and other molecules in Pluto’s atmosphere. These hydrocarbons accumulate into small haze particles, which scatter blue sunlight—the same process that can make haze appear bluish on Earth.

10. Encore

On Jan. 1, 2019, New Horizons will fly past a small Kuiper Belt Object named MU69 (nicknamed Ultima Thule)—a billion miles (1.5 billion kilometers) beyond Pluto and more than four billion miles (6.5 billion kilometers) from Earth. It will be the most distant encounter of an object in history—so far—and the second time New Horizons has revealed never-before-seen landscapes.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

More Posts from Sergioballester-blog and Others

NASA’s Search for Life: Astrobiology in the Solar System and Beyond

Are we alone in the universe? So far, the only life we know of is right here on Earth. But here at NASA, we’re looking.

We’re exploring the solar system and beyond to help us answer fundamental questions about life beyond our home planet. From studying the habitability of Mars, probing promising “oceans worlds,” such as Titan and Europa, to identifying Earth-size planets around distant stars, our science missions are working together with a goal to find unmistakable signs of life beyond Earth (a field of science called astrobiology).

Dive into the past, present, and future of our search for life in the universe.

Mission Name: The Viking Project

Launch: Viking 1 on August 20, 1975 & Viking 2 on September 9, 1975

Status: Past

Role in the search for life: The Viking Project was our first attempt to search for life on another planet. The mission’s biology experiments revealed unexpected chemical activity in the Martian soil, but provided no clear evidence for the presence of living microorganisms near the landing sites.

Mission Name: Galileo

Launch: October 18, 1989

Status: Past

Role in the search for life: Galileo orbited Jupiter for almost eight years, and made close passes by all its major moons. The spacecraft returned data that continues to shape astrobiology science –– particularly the discovery that Jupiter’s icy moon Europa has evidence of a subsurface ocean with more water than the total amount of liquid water found on Earth.

Mission Name: Kepler and K2

Launch: March 7, 2009

Status: Past

Role in the search for life: Our first planet-hunting mission, the Kepler Space Telescope, paved the way for our search for life in the solar system and beyond. Kepler left a legacy of more than 2,600 exoplanet discoveries, many of which could be promising places for life.

Mission Name: Perseverance Mars Rover

Launch: July 30, 2020

Status: Present

Role in the search for life: Our newest robot astrobiologist is kicking off a new era of exploration on the Red Planet. The rover will search for signs of ancient microbial life, advancing the agency’s quest to explore the past habitability of Mars.

Mission Name: James Webb Space Telescope

Launch: 2021

Status: Future

Role in the search for life: Webb will be the premier space-based observatory of the next decade. Webb observations will be used to study every phase in the history of the universe, including planets and moons in our solar system, and the formation of distant solar systems potentially capable of supporting life on Earth-like exoplanets.

Mission Name: Europa Clipper

Launch: Targeting 2024

Status: Future

Role in the search for life: Europa Clipper will investigate whether Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, with its subsurface ocean, has the capability to support life. Understanding Europa’s habitability will help scientists better understand how life developed on Earth and the potential for finding life beyond our planet.

Mission Name: Dragonfly

Launch: 2027

Status: Future

Role in the search for life: Dragonfly will deliver a rotorcraft to visit Saturn’s largest and richly organic moon, Titan. This revolutionary mission will explore diverse locations to look for prebiotic chemical processes common on both Titan and Earth.

For more on NASA’s search for life, follow NASA Astrobiology on Twitter, on Facebook, or on the web.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

jupiter

Just storm in a Canada

![Voyager 1 Approaching Jupiter In 1979. [Reddit/spacegifs]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/57003d3715c75582218ee1b20aeb6a70/tumblr_p21webfuy81s04h2ho1_400.gif)

Voyager 1 approaching Jupiter in 1979. [Reddit/spacegifs]

It was time for their close-up. Two days ago Jupiter and Saturn passed a tenth of a degree from each other in what is known a Great Conjunction. Although the two planets pass each other on the sky every 20 years, this was the closest pass in nearly four centuries. Taken early in day of the Great Conjunction, the featured multiple-exposure combination captures not only both giant planets in a single frame, but also Jupiter's four largest moons (left to right) Callisto, Ganymede, Io, and Europa -- and Saturn's largest moon Titan.

Image Credit: Damian Peach

what is your favorite natural satellite?

Cassini Spacecraft: Top Discoveries

Our Cassini spacecraft has been exploring Saturn, its stunning rings and its strange and beautiful moons for more than a decade.

Having expended almost every bit of the rocket propellant it carried to Saturn, operators are deliberately plunging Cassini into the planet to ensure Saturn’s moons will remain pristine for future exploration – in particular, the ice-covered, ocean-bearing moon Enceladus, but also Titan, with its intriguing pre-biotic chemistry.

Let’s take a look back at some of Cassini’s top discoveries:

Titan

Under its shroud of haze, Saturn’s planet-sized moon Titan hides dunes, mountains of water ice and rivers and seas of liquid methane. Of the hundreds of moons in our solar system, Titan is the only one with a dense atmosphere and large liquid reservoirs on its surface, making it in some ways more like a terrestrial planet.

Both Earth and Titan have nitrogen-dominated atmospheres – over 95% nitrogen in Titan’s case. However, unlike Earth, Titan has very little oxygen; the rest of the atmosphere is mostly methane and traced amounts of other gases, including ethane.

There are three large seas, all located close to the moon’s north pole, surrounded by numerous smaller lakes in the northern hemisphere. Just one large lake has been found in the southern hemisphere.

Enceladus

The moon Enceladus conceals a global ocean of salty liquid water beneath its icy surface. Some of that water even shoots out into space, creating an immense plume!

For decades, scientists didn’t know why Enceladus was the brightest world in the solar system, or how it related to Saturn’s E ring. Cassini found that both the fresh coating on its surface, and icy material in the E ring originate from vents connected to a global subsurface saltwater ocean that might host hydrothermal vents.

With its global ocean, unique chemistry and internal heat, Enceladus has become a promising lead in our search for worlds where life could exist.

Iapetus

Saturn’s two-toned moon Iapetus gets its odd coloring from reddish dust in its orbital path that is swept up and lands on the leading face of the moon.

The most unique, and perhaps most remarkable feature discovered on Iapetus in Cassini images is a topographic ridge that coincides almost exactly with the geographic equator. The physical origin of the ridge has yet to be explained…

It is not yet year whether the ridge is a mountain belt that has folded upward, or an extensional crack in the surface through which material from inside Iapetus erupted onto the surface and accumulated locally.

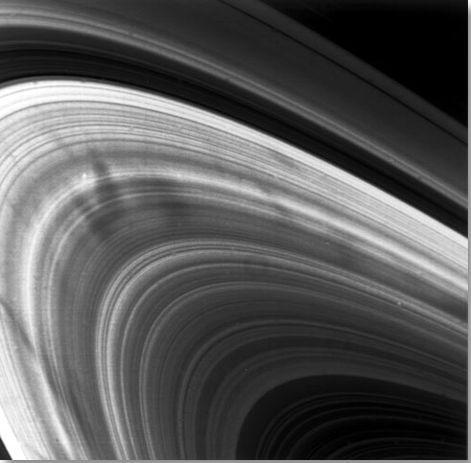

Saturn’s Rings

Saturn’s rings are made of countless particles of ice and dust, which Saturn’s moons push and tug, creating gaps and waves.

Scientists have never before studied the size, temperature, composition and distribution of Saturn’s rings from Saturn obit. Cassini has captured extraordinary ring-moon interactions, observed the lowest ring-temperature ever recorded at Saturn, discovered that the moon Enceladus is the source for Saturn’s E ring, and viewed the rings at equinox when sunlight strikes the rings edge-on, revealing never-before-seen ring features and details.

Cassini also studied features in Saturn’s rings called “spokes,” which can be longer than the diameter of Earth. Scientists think they’re made of thin icy particles that are lifted by an electrostatic charge and only last a few hours.

Auroras

The powerful magnetic field that permeates Saturn is strange because it lines up with the planet’s poles. But just like Earth’s field, it all creates shimmering auroras.

Auroras on Saturn occur in a process similar to Earth’s northern and southern lights. Particles from the solar wind are channeled by Saturn’s magnetic field toward the planet’s poles, where they interact with electrically charged gas (plasma) in the upper atmosphere and emit light.

Turbulent Atmosphere

Saturn’s turbulent atmosphere churns with immense storms and a striking, six-sided jet stream near its north pole.

Saturn’s north and south poles are also each beautifully (and violently) decorated by a colossal swirling storm. Cassini got an up-close look at the north polar storm and scientists found that the storm’s eye was about 50 times wider than an Earth hurricane’s eye.

Unlike the Earth hurricanes that are driven by warm ocean waters, Saturn’s polar vortexes aren’t actually hurricanes. They’re hurricane-like though, and even contain lightning. Cassini’s instruments have ‘heard’ lightning ever since entering Saturn orbit in 2004, in the form of radio waves. But it wasn’t until 2009 that Cassini’s cameras captured images of Saturnian lighting for the first time.

Cassini scientists assembled a short video of it, the first video of lightning discharging on a planet other than Earth.

Cassini’s adventure will end soon because it’s almost out of fuel. So to avoid possibly ever contaminating moons like Enceladus or Titan, on Sept. 15 it will intentionally dive into Saturn’s atmosphere.

The spacecraft is expected to lose radio contact with Earth within about one to two minutes after beginning its decent into Saturn’s upper atmosphere. But on the way down, before contact is lost, eight of Cassini’s 12 science instruments will be operating! More details on the spacecraft’s final decent can be found HERE.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

NASA’s Perseverance takes first photo.

-

lavenderdesa liked this · 1 year ago

lavenderdesa liked this · 1 year ago -

notgreek liked this · 1 year ago

notgreek liked this · 1 year ago -

juicythys liked this · 2 years ago

juicythys liked this · 2 years ago -

pebbs06 liked this · 3 years ago

pebbs06 liked this · 3 years ago -

archive-iii reblogged this · 3 years ago

archive-iii reblogged this · 3 years ago -

bailiemxo liked this · 3 years ago

bailiemxo liked this · 3 years ago -

violetchi-king liked this · 3 years ago

violetchi-king liked this · 3 years ago -

butchhatred liked this · 3 years ago

butchhatred liked this · 3 years ago -

a-mid-min liked this · 3 years ago

a-mid-min liked this · 3 years ago