Ricardocedillob - Sin Título

More Posts from Ricardocedillob and Others

Striges

The Helium Atom

Helium nuclei were created in the Big Bang and contain two protons and two neutrons each. Helium is the second most abundant element, comprising roughly one quarter of the mass of the Universe. This animation zooms into a standard helium atom, showing its protons (green), neutrons (white), and electrons (blue).

Credits: Dana Berry / Lead Animator Michael McClare (HTSI)

Our Weird and Wonderful Galaxy of Black Holes

Black holes are hard to find. Like, really hard to find. They are objects with such strong gravity that light can’t escape them, so we have to rely on clues from their surroundings to find them.

When a star weighing more than 20 times the Sun runs out of fuel, it collapses into a black hole. Scientists estimate that there are tens of millions of these black holes dotted around the Milky Way, but so far we’ve only identified a few dozen. Most of those are found with a star, each circling around the other. Another name for this kind of pair is a binary system.That’s because under the right circumstances material from the star can interact with the black hole, revealing its presence.

The visualization above shows several of these binary systems found in our Milky Way and its neighboring galaxy. with their relative sizes and orbits to scale. The video even shows each system tilted the way we see it here from our vantage point on Earth. Of course, as our scientists gather more data about these black holes, our understanding of them may change.

If the star and black hole orbit close enough, the black hole can pull material off of its stellar companion! As the material swirls toward the black hole, it forms a flat ring called an accretion disk. The disk gets very hot and can flare, causing bright bursts of light.

V404 Cygni, depicted above, is a binary system where a star slightly smaller than the Sun orbits a black hole 10 times its mass in just 6.5 days. The black hole distorts the shape of the star and pulls material from its surface. In 2015, V404 Cygni came out of a 25-year slumber, erupting in X-rays that were initially detected by our Swift satellite. In fact, V404 Cygni erupts every couple of decades, perhaps driven by a build-up of material in the outer parts of the accretion disk that eventually rush in.

In other cases, the black hole’s companion is a giant star with a strong stellar wind. This is like our Sun’s solar wind, but even more powerful. As material rushes out from the companion star, some of it is captured by the black hole’s gravity, forming an accretion disk.

A famous example of a black hole powered by the wind of its companion is Cygnus X-1. In fact, it was the first object to be widely accepted as a black hole! Recent observations estimate that the black hole’s mass could be as much as 20 times that of our Sun. And its stellar companion is no slouch, either. It weighs in at about 40 times the Sun.

We know our galaxy is peppered with black holes of many sizes with an array of stellar partners, but we've only found a small fraction of them so far. Scientists will keep studying the skies to add to our black hole menagerie.

Curious to learn more about black holes? Follow NASA Universe on Twitter and Facebook to keep up with the latest from our scientists and telescopes.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Hundreds Of Eggs From Ancient Flying Reptile Are Found In China

A cache of hundreds of eggs discovered in China sheds new light on the development and nesting behavior of prehistoric, winged reptiles called pterosaurs.

Pterosaurs were fearsome-looking creatures that flew during the Lower Cretaceous period alongside dinosaurs. This particular species was believed to have a massive wingspan of up to 13 feet, and likely ate fish with their large teeth-filled jaws.

Researchers working in the Turpan-Hami Basin in northwestern China collected the eggs over a 10-year span from 2006 to 2016.

A single sandstone block held at least 215 well-preserved eggs that have mostly kept their shape. Sixteen of those eggs have embryonic remains of the pterosaur species Hamipterus tianshanensis, the researchers said in findings released today in Science.

The fossils in the area are so plentiful that scientists refer to it as “Pterosaur Eden,” says Shunxing Jiang, a paleontologist at the Chinese Academy of Science’s Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology. “You can very easily find the pterosaur bones,” he says, adding that they believe dozens more eggs might still lie hidden within the sandstone.

Artist’s rendition of a family of pterosaurs, which had massive wingspans of up to 13 feet and likely ate fish with their large teeth-filled jaws. Illustrated by Zhao Chuang

Hundreds of pterosaur bones from the Lower Cretaceous period lie on the surface of an excavation site in the China’s Turpan-Hami Basin. Alexander Kellner/Museu Nacional/UFRJ

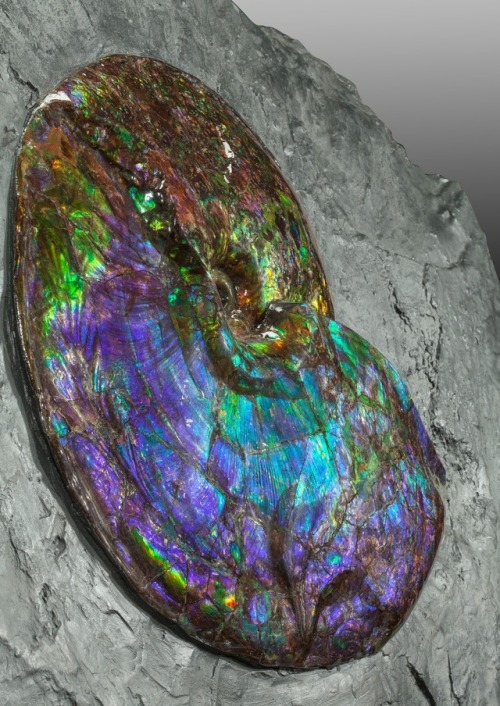

Ammonite in matrix (Placenticeras costatum, Late Cretaceous) - Bearpaw Formation, Alberta, Canada

-

bodega-vendetta reblogged this · 10 months ago

bodega-vendetta reblogged this · 10 months ago -

dvin9 liked this · 1 year ago

dvin9 liked this · 1 year ago -

vyvvvyv reblogged this · 3 years ago

vyvvvyv reblogged this · 3 years ago -

aloian liked this · 5 years ago

aloian liked this · 5 years ago -

satedsevendevils liked this · 5 years ago

satedsevendevils liked this · 5 years ago -

nubare liked this · 5 years ago

nubare liked this · 5 years ago -

monkeymanweb reblogged this · 5 years ago

monkeymanweb reblogged this · 5 years ago -

qqqbiland liked this · 6 years ago

qqqbiland liked this · 6 years ago -

l97ll liked this · 6 years ago

l97ll liked this · 6 years ago -

epikepitepi reblogged this · 6 years ago

epikepitepi reblogged this · 6 years ago -

epikepitepi liked this · 6 years ago

epikepitepi liked this · 6 years ago -

ratsocks liked this · 6 years ago

ratsocks liked this · 6 years ago -

whitetrashgrandpa reblogged this · 6 years ago

whitetrashgrandpa reblogged this · 6 years ago -

creepycrappydelirium reblogged this · 6 years ago

creepycrappydelirium reblogged this · 6 years ago -

memeave reblogged this · 6 years ago

memeave reblogged this · 6 years ago -

anueutsuho liked this · 6 years ago

anueutsuho liked this · 6 years ago -

ddiibbblr liked this · 6 years ago

ddiibbblr liked this · 6 years ago -

ddiibbblr reblogged this · 6 years ago

ddiibbblr reblogged this · 6 years ago -

ethananderson liked this · 6 years ago

ethananderson liked this · 6 years ago -

andraz369 liked this · 6 years ago

andraz369 liked this · 6 years ago -

inmygarden900 reblogged this · 6 years ago

inmygarden900 reblogged this · 6 years ago -

remindereminder liked this · 6 years ago

remindereminder liked this · 6 years ago -

winhasworld-blog liked this · 6 years ago

winhasworld-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

yourbodyisawonderland reblogged this · 6 years ago

yourbodyisawonderland reblogged this · 6 years ago -

solost106 liked this · 6 years ago

solost106 liked this · 6 years ago -

parkerino liked this · 6 years ago

parkerino liked this · 6 years ago -

thegnomezilla reblogged this · 6 years ago

thegnomezilla reblogged this · 6 years ago -

sapphiconoclast reblogged this · 6 years ago

sapphiconoclast reblogged this · 6 years ago -

squidalee reblogged this · 6 years ago

squidalee reblogged this · 6 years ago -

paintbucket reblogged this · 6 years ago

paintbucket reblogged this · 6 years ago -

multiple-fish-cakes liked this · 6 years ago

multiple-fish-cakes liked this · 6 years ago -

heatandapathy reblogged this · 6 years ago

heatandapathy reblogged this · 6 years ago -

heatandapathy liked this · 6 years ago

heatandapathy liked this · 6 years ago -

gronhund liked this · 6 years ago

gronhund liked this · 6 years ago -

soapoey liked this · 6 years ago

soapoey liked this · 6 years ago -

voooooooooopooooooooo liked this · 6 years ago

voooooooooopooooooooo liked this · 6 years ago -

rvde liked this · 6 years ago

rvde liked this · 6 years ago -

ohmydamnhotgod liked this · 6 years ago

ohmydamnhotgod liked this · 6 years ago -

ladyqathrin reblogged this · 6 years ago

ladyqathrin reblogged this · 6 years ago