The Song “It’s A Long Way To Tipperary” Was Enormously Popular In New Zealand As A Sound Recording

The song “It’s a long way to Tipperary” was enormously popular in New Zealand as a sound recording sung by Stanley Kirkby, with shops advertising new arrivals of stock from overseas in early 1915. At the same time, a film of the same title was also being shown in cinemas, and sheet music for an orchestral arrangement was available at the “Golden Horn” music store in Vivian Street Wellington. Copies of this Maori postcard with its “Tipirere “ translation were handed out to members of the 2nd Maori Contingent of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force after they marched through the streets of Wellington on Saturday 16 September 1915 (See Evening Post, 20 September 1915, page 8).

[Postcard]. Tipirere. N.Z.M.E.C. Hokowhitu-a-Tu. [ca 1915].

Eph-B-POSTCARD-Vol-12-003-btm

More Posts from Philosophical-amoeba and Others

Prevalence of homosexuality in men is stable throughout time since many carry the genes

Around half of all heterosexual men and women potentially carry so-called homosexuality genes that are passed on from one generation to the next. This has helped homosexuality to be present among humans throughout history and in all cultures, even though homosexual men normally do not have many descendants who can directly inherit their genes. This idea is reported by Giorgi Chaladze of the Ilia State University in Georgia, and published in Springer’s journal Archives of Sexual Behavior. Chaladze used a computational model that, among others, includes aspects of heredity and the tendency of homosexual men to come from larger families.

Chaladze, G. Heterosexual Male Carriers Could Explain Persistence of Homosexuality in Men: Individual-Based Simulations of an X-Linked Inheritance Model. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 2016 DOI: 10.1007/s10508-016-0742-2

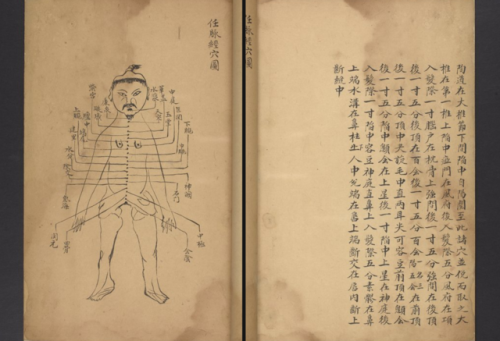

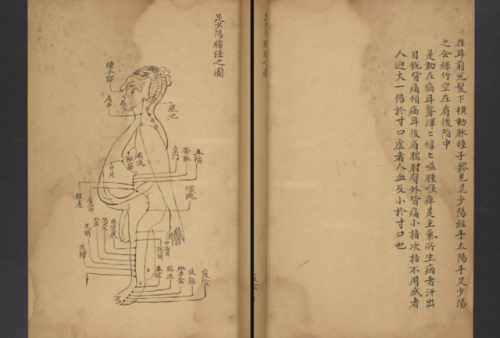

This week, we’re taking a look at manuscripts having to do with health, medicine, and human physiology specifically focusing on how bodies are displayed in manuscript illuminations or diagrams across different cultures.

LJS 389 shown above, is a 14th century Chinese treatise on the anatomy, physiology, and pathology of blood vessels titled Shi si jing fa hui. The manuscript is made from bamboo paper and the diagrams and kaishu script are written with black ink. Focus on the diagrams of the bodies and stay tuned this week to see not only how the details and forms of these depictions change from culture to culture, but also the mediums with which these manuscripts are created.

The full LJS 389 manuscript filled with more diagrams can be found on Openn: http://openn.library.upenn.edu/Data/0001/html/ljs389.html

and Penn In Hand: http://hdl.library.upenn.edu/1017/d/medren/4824235

Harmonograph, H. Irwine Whitty, 1893

“The facts that musical notes are due to regular air-pulses, and that the pitch of the note depends on the frequency with which these pulses succeed each other, are too well known to require any extended notice. But although these phenomena and their laws have been known for a very long time, Chladni, late in the last century, was the first who discovered that there was a connection between sound and form.”

source here

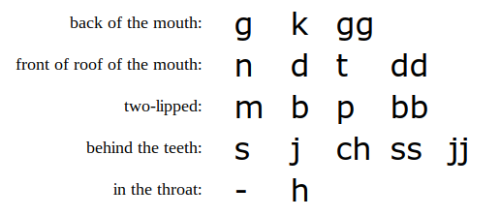

A basic schematic of why the Korean alphabet is so cool, from Wright House:

Unlike almost every other alphabet in the world, the Korean alphabet did not evolve. It was invented in 1443 (promulgated in 1446) by a team of linguists and intellectuals commissioned by King Sejong the Great.

In the diagram [above], the Korean consonants are arranged into five main linguistic groups (one per row), depending on where in the mouth contact is made. Notice that there is a graphic element common to all the consonants in a particular row. The first consonant in each row is the most basic and is graphically the simplest; this representative consonant for each group is the building block for the other characters in that group. Certain of these modifications are systematic, and yield similarly modified characters in several groups, such as adding a horizontal line to a simple consonant (a “stop” consonant–such as t/d or p/b–rather than a nasal consonant) to form the aspirated consonants (those made with extra air) and doubling simple consonants to form “tense” consonants (no real equivalent in English).

Notice that the five representative consonants (the ones in the first column in the upper part of the diagram) are also depicted in the drawings that make up the lower part of the diagram showing the relevant part of the mouth involved. Ingeniously, each of these representative consonants is a kind of simplified schematic diagram showing the position of the mouth in forming those consonants.

More details, including subsequent historical changes to Hangul, in the Wikipedia article.

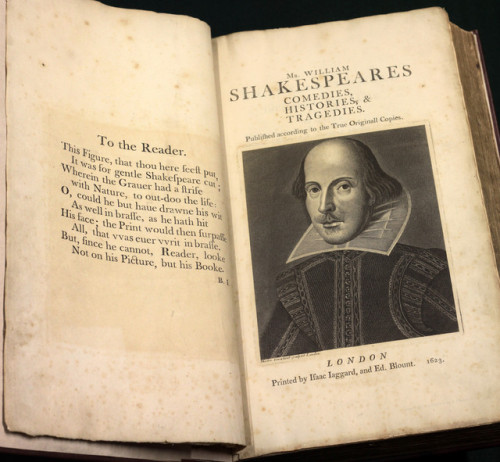

Comedies Histories Tragedies

Mr William Shakespeare

London Iaggard and Blount 1623

Textual reprint of the First Folio published by J Wright 1807

“Brainprint” Biometric ID Hits 100% Accuracy

Psychologists and engineers at Binghamton University in New York say they’ve hit a milestone in the quest to use the unassailable inner workings of the mind as a form of biometric identification. They came up with an electroencephalograph system that proved 100 percent accurate at identifying individuals by the way their brains responded to a series of images. But EEG as a practical means of authentication is still far off.

Many earlier attempts had come close to 100 percent accuracy but couldn’t completely close the gap. “It’s a big deal going from 97 to 100 percent because we imagine the applications for this technology being for high-security situations,” says Sarah Laszlo, the assistant professor of psychology at Binghamton who led the research with electrical engineering professor Zhanpeng Jin.

Perhaps as important as perfect accuracy is that this new form of ID can do something fingerprints and retinal scans have a hard time achieving: It can be “canceled.”

Fingerprint authentication can be reset if the associated data is stolen, because that data can be stored as a mathematically transformed version of itself, points out Clarkson University biometrics expert Stephanie Schuckers. However, that trick doesn’t work if it’s the fingerprint (or the finger) itself that’s stolen. And the theft part, at least, is easier than ever. In 2014 hackers claimed to have cloned German defense minister Ursula von der Leyen’s fingerprints just by taking a high-definition photo of her hands at a public event.

Several early attempts at EEG-based identification sought the equivalent of a fingerprint in the electrical activity of a brain at rest. But this new brain biometric, which its inventors call CEREBRE, dodges the cancelability problem because it’s based on the brain’s responses to a sequence of particular types of images. To keep that ID from being permanently hijacked, those images can be changed or re-sorted to essentially make a new biometric passkey, should the original one somehow be hacked.

CEREBRE, which Laszlo, Jin, and colleagues described in IEEE Transactions in Information Forensics and Security, involves presenting a person wearing an EEG system with images that fall into several categories: foods people feel strongly about, celebrities who also evoke emotions, simple sine waves of different frequencies, and uncommon words. The words and images are usually black and white, but occasionally one is presented in color because that produces its own kind of response.

Each image causes a recognizable change in voltage at the scalp called an event-related potential, or ERP. The different categories of images involve somewhat different combinations of parts of your brain, and they were already known to produce slight differences in the shapes of ERPs in different people. Laszlo’s hypothesis was that using all of them—several more than any other system—would create enough different ERPs to accurately distinguish one person from another.

The EEG responses were fed to software called a classifier. After testing several schemes, including a variety of neural networks and other machine-learning tricks, the engineers found that what actually worked best was a system based on simple cross correlation.

In the experiments, each of the 50 test subjects saw a sequence of 500 images, each flashed for 1 second. “We collected 500, knowing it was overkill,” Laszlo says. Once the researchers crunched the data they found that just 27 images would have been enough to hit the 100 percent mark.

The experiments were done with a high-quality research-grade EEG, which used 30 electrodes attached to the skull with conductive goop. However, the data showed that the system needs only three electrodes for 100 percent identification, and Laszlo says her group is working on simplifying the setup. They’re testing consumer EEG gear from Emotiv and NeuroSky, and they’ve even tried to replicate the work with electrodes embedded in a Google Glass, though the results weren’t spectacular, she says.

For EEG to really be taken seriously as a biometric ID, brain interfaces will need to be pretty commonplace, says Schuckers. That might yet happen. “As we go more and more into wearables as a standard part of our lives, [EEGs] might be more suitable,” she says.

But like any security system, even an EEG biometric will attract hackers. How can you hack something that depends on your thought patterns? One way, explains Laszlo, is to train a hacker’s brain to mimic the right responses. That would involve flashing light into a hacker’s eye at precise times while the person is observing the images. These flashes are known to alter the shape of the ERP.

Are Complex Numbers Really Numbers?

If you look through definitions of “number” most will say that numbers are used to represent quantities (amounts or measures). Whole numbers 0, 1, 2, 3, … are probably the first numbers that come to mind and they are often used to count things like say how may watermelons jimmy has. But when quantifying things like money, whole numbers are not always enough and so we have rational numbers (which include the whole numbers but also fractions and numbers with finite or repeating decimal expansions). Yet, sometimes even these numbers are not enough to express certain quantities. Pi, for example, is not a rational number but is certainly a number as it represents the quantity that is the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter. It can be shown that the number pi has an infinite decimal expansion with no repeating patterns, and so a number like pi is called an irrational number. (Because they are silly? Although at first some thought so, the term irrational just means not rational.) More specifically, pi is a transcendental number as it is not the root of any polynomial. (Transcendental, because they transcend the usual notion of number? Idk. Again, strange names.) So, the rational numbers were extended to the real numbers to include both rational and irrational numbers. Either way, we see that both rational and irrational numbers are truly numbers since they can be used to represent quantities.

What about complex numbers though? Are they really numbers, or do people just call them “numbers”? So, we should ask, can complex numbers represent some amount or measure of something? Can jimmy have i watermelons? No, but jimmy can’t really have pi watermelons either and pi is a number. Jimmy may have a watermelon that weighs pi pounds though (the only way to know this would be if jimmy had a scale with infinite accuracy, which, turns out, he does). Okay but can jimmy have a watermelon weighing i pounds? That doesn’t seem to make sense. To see if complex numbers can represent quantities we need to elaborate on what complex numbers are exactly.

The complex numbers are the real numbers extended to include the square root of negative 1 (i) and all its multiples. They have the form a+bi where a and b are real numbers. i is called an imaginary number (named imaginary because, i is not a real number, but this implies numbers like i are somehow not “real”, in the usual English sense of the word (are any numbers really “real”?) again, with the names). What truly makes complex numbers different than the other numbers we have discussed is that they “live” in 2 dimensions (the complex plane); complex numbers (e.g., 7+2i) have a real part (7) and an imaginary part (2i). While real numbers (which include whole, rational, and irrational numbers) “live” in one dimension (they can be found anywhere on the number line).

So, a complex number is a sort of two-dimensional quantity, it has a real measure and an imaginary measure. This makes them strange as numbers. We know 12 is bigger than 11 and that there are a bunch of numbers in-between 11 and 12, but which is bigger 2-8i or 3+i? Complex numbers cannot be compared in the same way i.e., there is no way to order complex numbers from smallest to largest.

These properties make complex numbers more abstract than typical numbers we encounter day to day. Nevertheless, “complex numbers are useful abstract quantities that can be used in calculations and result in physically meaningful solutions. However, recognition of this fact is one that took a long time for mathematicians to accept.”—Wolfram MathWorld http://mathworld.wolfram.com/ComplexNumber.html

How many did you know? All worth reading more about!!

11 New Facts Science Has Revealed About The Body

1. Hundreds of genes spring to life after you die - and they keep functioning for up to four days.

2. Livers grow by almost half during waking hours.

3. The root cause of eczema has finally been identified.

4. We were wrong - the testes are connected to the immune system after all.

5. The causes of hair loss and greying are linked, and for the first time, scientists have identified the cells responsible.

6. A brand new human organ has been classified - the mesentery - an organ that’s been hiding in plain sight in our digestive system this whole time.

7. An unexpected new lung function has been found - they also play a key role in blood production, with the ability to produce more than 10 million platelets (tiny blood cells) per hour.

8. Your appendix might actually be serving an important biological function- and one that our species isn’t ready to give up just yet.

9. The brain literally starts eating itself when it doesn’t get enough sleep. brain to clear a huge amount of neurons and synaptic connections away.

10. Neuroscientists have discovered a whole new role for the brain’s cerebellum - it could actually play a key role in shaping human behaviour.

11. Our gut bacteria are messing with us in ways we could never have imagined. Neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s might actually start out in the gut, rather than the brain, and there’s mounting evidence that the human microbiome could be to blame for chronic fatigue syndrome.

Four years of failed harvests (1695, 1696, and 1698–99) resulted in severe famine and depopulation, particularly in the north of Scotland. Starvation killed 5 to 15 percent of the Scottish population, but in areas such as Aberdeenshire, death rates reached 25 percent.

Rarely has a natural disaster had such wide-ranging historical consequences as did the famine that struck Scotland in the mid-1690s. Little more than a decade later, as Scotland’s social elites despaired about their nation’s grinding poverty and profound structural weakness, the country’s Parliament finally voted away its age-old independence in favor of unification with England, previously Scotland’s bitterest and most enduring enemy.

The author of this sermon was a very colorful figure. A Scottish Presbyterian minister denounced as a rebel in 1674, he was restored next year but arrested again the following February. Later he was arrested for refusing to pray for the Prince of Wales, but again released. His matrimonial adventures were no less robust than his professional career. He was married seven times and fathered at least nine children.

David Williamson (1636- 1706). Scotland’s sin, danger, and duty: faithfully represented in a sermon preach’d at the West-Kirk, August 23d, 1696: being a solemn fast-day upon occasion of the great dearth and famine. Rare BT162.F3 W54 1720

-

irgum-burgum liked this · 3 years ago

irgum-burgum liked this · 3 years ago -

theegoist liked this · 3 years ago

theegoist liked this · 3 years ago -

americanappall liked this · 3 years ago

americanappall liked this · 3 years ago -

ffactory reblogged this · 3 years ago

ffactory reblogged this · 3 years ago -

noceiling-m liked this · 4 years ago

noceiling-m liked this · 4 years ago -

lilybarthes reblogged this · 4 years ago

lilybarthes reblogged this · 4 years ago -

lilybarthes liked this · 4 years ago

lilybarthes liked this · 4 years ago -

uss-edsall liked this · 7 years ago

uss-edsall liked this · 7 years ago -

khailea liked this · 8 years ago

khailea liked this · 8 years ago -

poemwriter98 liked this · 8 years ago

poemwriter98 liked this · 8 years ago -

hildegard-von-bingen reblogged this · 8 years ago

hildegard-von-bingen reblogged this · 8 years ago -

old-ish-survivor liked this · 8 years ago

old-ish-survivor liked this · 8 years ago -

pantheonofjoy liked this · 8 years ago

pantheonofjoy liked this · 8 years ago -

andriacrowjoy liked this · 8 years ago

andriacrowjoy liked this · 8 years ago -

thisisafter reblogged this · 8 years ago

thisisafter reblogged this · 8 years ago -

yukonsoda liked this · 8 years ago

yukonsoda liked this · 8 years ago -

atypeoftim liked this · 8 years ago

atypeoftim liked this · 8 years ago -

herverthoober reblogged this · 8 years ago

herverthoober reblogged this · 8 years ago -

1901-a-space-odyssey reblogged this · 8 years ago

1901-a-space-odyssey reblogged this · 8 years ago -

richardoverell liked this · 8 years ago

richardoverell liked this · 8 years ago -

zeehasablog reblogged this · 8 years ago

zeehasablog reblogged this · 8 years ago -

iandallamba liked this · 8 years ago

iandallamba liked this · 8 years ago -

sagasandtales liked this · 8 years ago

sagasandtales liked this · 8 years ago -

low-hedge-sad-hedge liked this · 8 years ago

low-hedge-sad-hedge liked this · 8 years ago -

averyterrible reblogged this · 8 years ago

averyterrible reblogged this · 8 years ago -

space-magnetic liked this · 8 years ago

space-magnetic liked this · 8 years ago -

cuimhnigh-i-gconai reblogged this · 8 years ago

cuimhnigh-i-gconai reblogged this · 8 years ago -

cuimhnigh-i-gconai liked this · 8 years ago

cuimhnigh-i-gconai liked this · 8 years ago -

an-moncai-mishuaimhneach reblogged this · 8 years ago

an-moncai-mishuaimhneach reblogged this · 8 years ago -

heaveninawildflower liked this · 8 years ago

heaveninawildflower liked this · 8 years ago -

crustyoldhag reblogged this · 8 years ago

crustyoldhag reblogged this · 8 years ago -

zeehasablog liked this · 8 years ago

zeehasablog liked this · 8 years ago -

ammg-old reblogged this · 8 years ago

ammg-old reblogged this · 8 years ago -

philosophical-amoeba reblogged this · 8 years ago

philosophical-amoeba reblogged this · 8 years ago -

goodassbreath reblogged this · 8 years ago

goodassbreath reblogged this · 8 years ago -

goodassbreath liked this · 8 years ago

goodassbreath liked this · 8 years ago -

giorgioooo-blog1 liked this · 8 years ago

giorgioooo-blog1 liked this · 8 years ago -

cattraine reblogged this · 8 years ago

cattraine reblogged this · 8 years ago -

kiwianaroha reblogged this · 8 years ago

kiwianaroha reblogged this · 8 years ago -

strangewastelandpersona liked this · 8 years ago

strangewastelandpersona liked this · 8 years ago -

gmayan888 liked this · 8 years ago

gmayan888 liked this · 8 years ago -

slnswmaps liked this · 8 years ago

slnswmaps liked this · 8 years ago -

jvcarmic46 liked this · 8 years ago

jvcarmic46 liked this · 8 years ago -

watsdaughter reblogged this · 8 years ago

watsdaughter reblogged this · 8 years ago

A reblog of nerdy and quirky stuff that pique my interest.

291 posts