Image: The Libertine Falstaff Sits With A Woman On His Lap And A Tankard In His Hand In An Illustrated

Image: The libertine Falstaff sits with a woman on his lap and a tankard in his hand in an illustrated scene from one of William Shakespeare’s Henry IV plays. (Kean Collection/Getty Images)

The eggplant and peach emoji are standard code for racy thoughts these days, but people have been using food as sexual innuendo for centuries. In fact, William Shakespeare was a pro at the gastronomic double entendre [insert blushing face emoji here]. The Salt blog asked a Shakespeare expert to help them decode some of the bard’s bawdy food jokes. (And the result is delightful. – Nicole)

50 Shades Of Shakespeare: How The Bard Used Food As Racy Code

More Posts from Philosophical-amoeba and Others

Don’t play, play - Singlish is studied around the globe

Blogger Wendy Cheng’s Web video series Xiaxue’s Guide To Life and Jack Neo’s Ah Boys To Men film franchise are well-known shows among Singaporeans. For one thing, they are filled with colloquial terms, local references and copious doses of Singlish terms such as “lah” and “lor”.

But they are not merely for entertainment. In recent years, such shows have found a place in universities around the world, where linguists draw on dialogues used in these local productions to introduce to undergraduates and postgraduate students how Singlish has become a unique variety of the English language.

This comes even as concerns have been raised over how Singlish could impede the use of standard English here.

From Italy and Germany to Japan, at least seven universities around the world have used Singlish as a case study in linguistics courses over the past decade. This is on top of more than 40 academics outside of Singapore - some of whom were previously based here - who have written books or papers on Singlish as part of their research.

A history of note

In 2016 the Bank of England will issue their first polymer (plastic) banknotes. Here’s a brief history of the banknote, from Chinese origins to a worldwide phenomenon.

Paper currency was first used in China as early as AD 1000. It was the Chinese who first printed a value on a piece of paper and persuaded everyone that it was worth what it said it was. The whole modern banking system of paper and credit is built on this one simple act of faith. The Chinese had invented both paper and block printing, and this allowed the printing of paper money.

The Chinese writing along the top of this Ming dynasty banknote reads (from right to left): ‘Da Ming tong xing bao chao’ and translates as ‘Great Ming Circulating Treasure Note’. You can find out more about it here.

The Ming were the first Chinese dynasty to try to totally replace coins with paper money. After seizing power from the Mongol rulers of China in 1368, the rulers of the Ming dynasty tried to reinstate bronze coins. However, there was not enough metal available for this, and paper money, made of mulberry bark, was produced from 1375. Paper money continued to be issued throughout the Ming dynasty, but inflation quickly eroded its value. The effect of inflation was so devastating that paper money was regarded with suspicion for many years and it was not until the 1850s that paper money was issued again.

The first banknotes in Europe were issued in Sweden by the Stockholm Banco, set up in 1656 by merchant Johan Palmstruch. It produced its first notes a few years later, in 1661, as an alternative to the huge and inconvenient copper plate money which was then in circulation in Sweden. Though the designs of these early notes were simple, they were carefully printed on handmade paper. They were given official authority by impressions of several seals, including the seal of the bank, and no less than eight handwritten signatures. Johan Palmstruch’s own signature can be seen here at the top of the list, on the left of the note. The Stockholm Banco was a private business, but it had close connections with the Swedish crown and the government. It was very successful at first, but then lent too much money and issued too many notes without proper backing. Palmstruch was blamed for the difficulties and imprisoned for mismanagement. Despite the failure of his bank, he is remembered now for introducing notes which were passed freely as money, just like the banknotes that we use today.

Bills of exchange evolved with the growth of banking in Europe from the 13th century. Paper money like the banknotes we use today was not then part of everyday currency in the West, but bankers and merchants did use written records for settling payments, especially in trade. In their simplest form, bills of exchange were written instructions by one person to an agent, authorising payment to a named individual or firm at a specified future date. They were therefore a convenient way of providing credit or making payments over a distance. In this example, John Emerson in Hamburg has instructed Austin Goodwin, a merchant in Bristol, to pay £380 to Joachim Coldorph in three months’ time. If Coldorph needed money sooner, he might choose to sell the bill to a fourth party at a discounted rate. That buyer would then present the bill for payment in Bristol at the appointed date.

In the mid-19th century, individual banks in the American states issued many different banknotes. This continued during the Civil War (1861–1865), but new paper money issued by the treasuries of the United States in New York and the Confederate States in Richmond reflected the political conflict. In the North, the first public paper money issued under the Constitution of the United States was authorised in July 1861, to finance war with the Confederacy. The back of the notes were printed in green, giving rise to the nickname ‘greenbacks’ for American bills. The colour green was chosen as that colour ink best stuck to the paper. The note shown here is an example of the second issue of 1862. On the front is a portrait of Salmon P Chase, Secretary to the Treasury.

During the First World War (1914–1918) a shortage of coins encouraged towns and regions in several European countries to issue local notes worth small sums. In Germany this Notgeld (‘emergency money’) became popular as a theme for collecting, and by the 1920s these tiny notes were produced in vast numbers with collecting, rather than spending, in mind. Designs on the notes ranged from wartime propaganda to local views or scenes from folklore. This example from the town of Hameln (Hamelin), in bright primary colours, refers to the Pied Piper, the legendary rat catcher who lured the children of the town to their deaths in the 13th century. A whole sequence of notes was issued, each one illustrating a different part of the tale.

The issuing of the £5 polymer banknote, which will bear the portrait of Sir Winston Churchill, means that England joins the growing number of countries who already use polymer technology. The durability and increased security afforded by the plastic notes have made them an attractive proposition to issuing authorities throughout the world from Australia and Nigeria to Brazil and Canada. This image shows a sheet of 32 uncut polymer banknotes printed for Clydesdale Bank in Scotland in 2015.

Discover the history of money in the British Museum’s Citi Money Gallery (Room 68), supported by Citi.

Awesome things you can do (or learn) through TensorFlow. From the site:

A Neural Network Playground

Um, What Is a Neural Network?

It’s a technique for building a computer program that learns from data. It is based very loosely on how we think the human brain works. First, a collection of software “neurons” are created and connected together, allowing them to send messages to each other. Next, the network is asked to solve a problem, which it attempts to do over and over, each time strengthening the connections that lead to success and diminishing those that lead to failure. For a more detailed introduction to neural networks, Michael Nielsen’s Neural Networks and Deep Learning is a good place to start. For more a more technical overview, try Deep Learning by Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville.

GitHub

h-t FlowingData

Why do we love?

Ah, romantic love; beautiful and intoxicating, heart-breaking and soul-crushing… often all at the same time! Why do we choose to put ourselves though its emotional wringer? Does love make our lives meaningful, or is it an escape from our loneliness and suffering? Is love a disguise for our sexual desire, or a trick of biology to make us procreate? Is it all we need? Do we need it at all?

If romantic love has a purpose, neither science nor psychology has discovered it yet – but over the course of history, some of our most respected philosophers have put forward some intriguing theories.

1. Love makes us whole, again / Plato (427—347 BCE)

The ancient Greek philosopher Plato explored the idea that we love in order to become complete. In his Symposium, he wrote about a dinner party at which Aristophanes, a comic playwright, regales the guests with the following story. Humans were once creatures with four arms, four legs, and two faces. One day they angered the gods, and Zeus sliced them all in two. Since then, every person has been missing half of him or herself. Love is the longing to find a soul mate who will make us feel whole again… or at least that’s what Plato believed a drunken comedian would say at a party.

2. Love tricks us into having babies / Schopenhauer (1788-1860)

Much, much later, German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer maintained that love, based in sexual desire, was a “voluptuous illusion”. He suggested that we love because our desires lead us to believe that another person will make us happy, but we are sorely mistaken. Nature is tricking us into procreating and the loving fusion we seek is consummated in our children. When our sexual desires are satisfied, we are thrown back into our tormented existences, and we succeed only in maintaining the species and perpetuating the cycle of human drudgery. Sounds like somebody needs a hug.

3. Love is escape from our loneliness / Russell (1872-1970)

According to the Nobel Prize-winning British philosopher Bertrand Russell we love in order to quench our physical and psychological desires. Humans are designed to procreate; but, without the ecstasy of passionate love, sex is unsatisfying. Our fear of the cold, cruel world tempts us to build hard shells to protect and isolate ourselves. Love’s delight, intimacy, and warmth helps us overcome our fear of the world, escape our lonely shells, and engage more abundantly in life. Love enriches our whole being, making it the best thing in life.

4. Love is a misleading affliction / Buddha (~6th- 4thC BCE)

Siddhartha Gautama. who became known as ‘the Buddha’, or ‘the enlightened one’, probably would have had some interesting arguments with Russell. Buddha proposed that we love because we are trying to satisfy our base desires. Yet, our passionate cravings are defects, and attachments – even romantic love – are a great source of suffering. Luckily, Buddha discovered the eight-fold path, a sort of program for extinguishing the fires of desire so that we can reach ‘nirvana’ – an enlightened state of peace, clarity, wisdom, and compassion.

5. Love lets us reach beyond ourselves / Beauvoir (1908-86)

Let’s end on a slightly more positive note. The French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir proposed that love is the desire to integrate with another and that it infuses our lives with meaning. However, she was less concerned with why we love and more interested in how we can love better. She saw that the problem with traditional romantic love is it can be so captivating that we are tempted to make it our only reason for being. Yet, dependence on another to justify our existence easily leads to boredom and power games.

To avoid this trap, Beauvoir advised loving authentically, which is more like a great friendship: lovers support each other in discovering themselves, reaching beyond themselves, and enriching their lives and the world, together.

Though we might never know why we fall in love, we can be certain that it’ll be an emotional rollercoaster ride. It’s scary and exhilarating. It makes us suffer and makes us soar. Maybe we lose ourselves. Maybe we find ourselves. It might be heartbreaking or it might just be the best thing in life. Will you dare to find out?

From the TED-Ed Lesson Why do we love? A philosophical inquiry - Skye C. Cleary

Animation by Avi Ofer

I made this to put on my wall for revision, but I thought it might be helpful for some of you guys too so I thought I would share it!

Dress for the job you want.

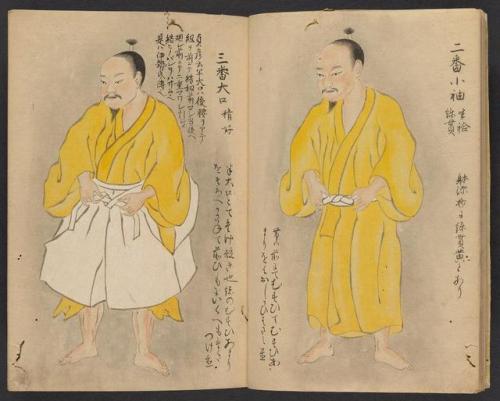

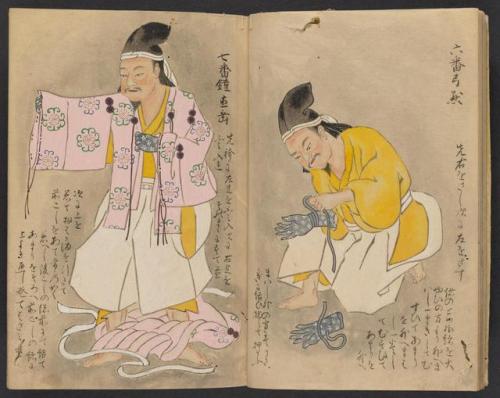

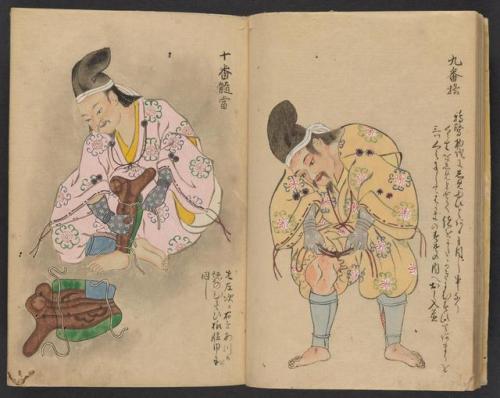

Yoshiie Ason yoroi chakuyōzu 義家朝臣鎧着用次第 by Sadatake Ise is a pictorial work on how to put on Japanese Samurai armor. The subject is famed Samurai warrior Minamoto No Yoshiie.

Find more amazing rare books we’ve recently digitized from our Freer | Sackler branch library in our book collection, Japanese Illustrated Books from the Edo and Meiji Period.

Staff Pick of the Week

As a lover of mythology and folklore, my first staff pick is The Wonder-Smith and His Son, by Ella Young (1867-1956), with illustrations by Boris Artzybasheff (1899-1965). It was published by Longmans, Green Co. in 1927 and was a Newbery Honor recipient in 1928. The book is a collection of myths from Ireland and Scotland about a legendary wonder smith known as the Gubbaun Saor, a “maker of worlds and a shaper of universes.” There are fourteen stories in the collection, detailing how the Gubbaun Saor got his world-building abilities, which involved finding a bag of magical tools that were dropped from the sky by a bird. The book also includes tales about his adopted son Lugh and his daughter Aunya. In her memoir, Flowering Dusk: Things Remembered Accurately and Inaccurately, Young wrote “I have a fondness for The Wonder-Smith; perhaps because I did not invent the stories in the book. I gathered them through twenty-five years of searching, and put a thread of prose round them.” The folktales were collected from story-tellers in Clare, Achill Island, Aranmore, and the Curraun.

Ella Young’s interest in Celtic mythology led to her becoming involved with the growing Irish nationalist movement. Many nationalist writers and artists were looking to Ireland’s history and legends for inspiration, and she befriended fellow Irish writers Æ (George William Russell), Padraic Colum, and William Butler Yeats. Æ called her “a druidess reincarnated.” Aside from publishing poetry and folklore, Yong was also involved in running guns and ammunition to the Irish Republican Army, and was a member of Cumann na mBAn, a women’s paramilitary organization that took part in the 1916 Easter Rising. She continued to write throughout the war, and in 1925 embarked for America to do a speaking tour about Celtic mythology at universities across the country. She was eventually granted American citizenship and accepted a teaching position at the University of California, Berkeley. Often described as mystical and otherworldly, Young lived out the rest of her life near the California coast writing and publishing stories and sharing her love of folklore with those around her.

Ukrainian illustrator Boris Artzybasheff fled the Russian Revolution for the United States in 1919. Beginning his career as an engraver, Artzybasheff soon became a book illustrator, some of which he wrote himself, such as Seven Simeons: A Russian Tale, which received a Caldecott Honor award in 1938. He is best known for his magazine covers, and he created over 200 covers for Time magazine alone. Over the course of his career his work evolved to become wonderfully surrealist, he loved anthropomorphizing machines so they would have human attributes and emotions. Even his commercial work in advertising has elements of the absurd. I believe Artzybasheff’s playfulness is evident in the woodcuts he did for The Wonder-Smith, and his illustrations are what drew me to the book.

– Sarah, Special Collections Undergraduate Assistant

Fuji-Ya Restaurant, Second to None

In 1968, Reiko Weston opened her new Fuji-Ya restaurant built atop the limestone foundation of a 19th-century flour mill overlooking the Mississippi River and the Stone Arch Bridge. The original Fuji-Ya restaurant operated near 8th St. and LaSalle beginning almost a decade earlier, in 1959, and served fine Japanese food including Charcoal-Broiled Teri-Yaki dinners, seafood dishes, soups, rice plates, and more. Fuji-Ya translates to “second to none” and the new restaurant offered a dining experience like no other in the Twin Cities.

Weston’s restaurant business expanded over the years with Taiga, a Chinese Szechwan restaurant in St. Anthony Main, and The Fuji International in Cedar-Riverside neighborhood, which featured Korean, Chinese, and East Indian food in addition to Japanese food. Her restaurants received numerous awards and Weston herself was named Minnesota Small Business Person of the Year in 1979.

After Reiko Weston passed away in 1988, her daughter Carol stepped in to manage. But in 1990, the City of Minneapolis bought out the historic restaurant in order to make way for the newly designed parkway. About a decade later, Fuji Ya was brought to life again in Uptown in the trendy Lyn-Lake area, where it remains today.

Recently, Fuji-Ya has gained renewed attention as the Park Board makes plans for a $12 million riverfront refresh. Plans include the teardown of the old Fuji-Ya building, expansion of green space, improved pedestrian crossings, and the addition of a new riverfront restaurant. It was announced last week that Sioux Chef owners Sean Sherman and Dana Thompson will open Owamni: An Indigenous Kitchen on the site.

Menu from the original Fuji-Ya restaurant at 814 LaSalle Ave. from the Minneapolis History Collection Menu Collection. Photos from the Star Tribune Photograph Collection at the James K. Hosmer Special Collections, Hennepin County Library.

-

linguisticsfetishist reblogged this · 4 years ago

linguisticsfetishist reblogged this · 4 years ago -

jwa007 liked this · 6 years ago

jwa007 liked this · 6 years ago -

coolbooksandqoutes-blog reblogged this · 6 years ago

coolbooksandqoutes-blog reblogged this · 6 years ago -

thelazybookcollector reblogged this · 8 years ago

thelazybookcollector reblogged this · 8 years ago -

mysteriousmanwiththehat-blog liked this · 9 years ago

mysteriousmanwiththehat-blog liked this · 9 years ago -

ravenmusewulfsong liked this · 9 years ago

ravenmusewulfsong liked this · 9 years ago -

lakeswalker liked this · 9 years ago

lakeswalker liked this · 9 years ago -

philosophical-amoeba reblogged this · 9 years ago

philosophical-amoeba reblogged this · 9 years ago -

elementx137 reblogged this · 9 years ago

elementx137 reblogged this · 9 years ago -

george-squashington liked this · 9 years ago

george-squashington liked this · 9 years ago -

lookitsaflyinghat liked this · 9 years ago

lookitsaflyinghat liked this · 9 years ago -

chussanchez5 liked this · 9 years ago

chussanchez5 liked this · 9 years ago -

valeriepeterson6 reblogged this · 9 years ago

valeriepeterson6 reblogged this · 9 years ago -

wishfulsaint reblogged this · 9 years ago

wishfulsaint reblogged this · 9 years ago -

zaq56 liked this · 9 years ago

zaq56 liked this · 9 years ago -

fearlesssirfinch reblogged this · 9 years ago

fearlesssirfinch reblogged this · 9 years ago -

crackingcheese liked this · 9 years ago

crackingcheese liked this · 9 years ago -

greenandpurplepolkadots liked this · 9 years ago

greenandpurplepolkadots liked this · 9 years ago -

muddydawg liked this · 9 years ago

muddydawg liked this · 9 years ago -

blackcatcuriosities liked this · 9 years ago

blackcatcuriosities liked this · 9 years ago -

plurdledgabbleblotchits liked this · 9 years ago

plurdledgabbleblotchits liked this · 9 years ago -

areyounobodytoo reblogged this · 9 years ago

areyounobodytoo reblogged this · 9 years ago -

hazelwords liked this · 9 years ago

hazelwords liked this · 9 years ago -

somesmallflicker liked this · 9 years ago

somesmallflicker liked this · 9 years ago -

lookashiny liked this · 9 years ago

lookashiny liked this · 9 years ago -

the-fairest-pear reblogged this · 9 years ago

the-fairest-pear reblogged this · 9 years ago -

anandalisa reblogged this · 9 years ago

anandalisa reblogged this · 9 years ago -

ktquimby reblogged this · 9 years ago

ktquimby reblogged this · 9 years ago -

susieqlinysusan-blog liked this · 9 years ago

susieqlinysusan-blog liked this · 9 years ago -

themusicsonrepeat reblogged this · 9 years ago

themusicsonrepeat reblogged this · 9 years ago -

justjanesworld liked this · 9 years ago

justjanesworld liked this · 9 years ago -

academicchris reblogged this · 9 years ago

academicchris reblogged this · 9 years ago -

academicchris liked this · 9 years ago

academicchris liked this · 9 years ago -

kyrilion liked this · 9 years ago

kyrilion liked this · 9 years ago -

kenzie2482-blog liked this · 9 years ago

kenzie2482-blog liked this · 9 years ago -

dj-da-vinci liked this · 9 years ago

dj-da-vinci liked this · 9 years ago -

laughing-baubo reblogged this · 9 years ago

laughing-baubo reblogged this · 9 years ago -

laughing-baubo liked this · 9 years ago

laughing-baubo liked this · 9 years ago -

specialkrr liked this · 9 years ago

specialkrr liked this · 9 years ago -

loganinpdx reblogged this · 9 years ago

loganinpdx reblogged this · 9 years ago -

brisuscheez liked this · 9 years ago

brisuscheez liked this · 9 years ago -

thejollyshiner reblogged this · 9 years ago

thejollyshiner reblogged this · 9 years ago

A reblog of nerdy and quirky stuff that pique my interest.

291 posts