Give Thanks.

Give thanks.

More Posts from Patz30 and Others

Physical Science...In Space!

Each month, we highlight a different research topic on the International Space Station. In May, our focus is physical science.

The space station is a laboratory unlike any on Earth; on-board, we can control gravity as a variable and even remove it entirely from the equation. Removing gravity reveals fundamental aspects of physics hidden by force-dependent phenomena such as buoyancy-driven convection and sedimentation.

Gravity often masks or distorts subtle forces such as surface tension and diffusion; on space station, these forces have been harnessed for a wide variety of physical science applications (combustion, fluids, colloids, surface wetting, boiling, convection, materials processing, etc).

Other examples of observations in space include boiling in which bubbles do not rise, colloidal systems containing crystalline structures unlike any seen on Earth and spherical flames burning around fuel droplets. Also observed was a uniform dispersion of tin particles in a liquid melt, instead of rising to the top as would happen in Earth’s gravity.

So what? By understanding the fundamentals of combustion and surface tension, we may make more efficient combustion engines; better portable medical diagnostics; stronger, lighter alloys; medicines with longer shelf-life, and buildings that are more resistant to earthquakes.

Findings from physical science research on station may improve the understanding of material properties. This information could potentially revolutionize development of new and improved products for use in everything from automobiles to airplanes to spacecraft.

For more information on space station research, follow @ISS_Research on Twitter!

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

The frog leap was captured on camera.

Facebook | Instagram | Scary Story Website

Amazing!

Zebra finch parents tell eggs: It’s hot outside

By calling to their eggs, zebra finch parents may be helping their young prepare for a hotter world brought on by climate change.

Sand stars may seem sleepy, but when seen sped up, turning minutes to seconds, their sandy strolls surge into serious sprints!

Can SciFi be used for SciComm?

A few weeks ago, one of our academic team (John White), wrote a hypothetical piece on what may happen to our ecosystems and species if we fail to act on climate change now. It was written as an obituary for a species in a future time.

You can check out the article here https://johnwhitewildlife.wordpress.com/2016/05/09/today-we-announce-antechinus-agilis-extinct-in-the-grampians/

The blog post was heavily read and was met with lots of differing opinions. The question being can SciFi be used to draw attention to critical issues such as Climate Change?

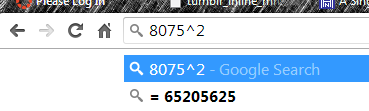

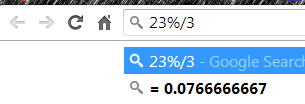

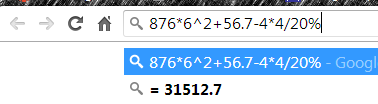

So Google does math for you??

division

square roots

dividing percentages

IT EVEN FOILS

beautiful.

Ukrainian pastry shop Musse Confectionery has created these amazing galaxy eclairs featuring aesthetic interstellar icing of various shades of blue, purple, and pink.

The Genius of Marie Curie

Growing up in Warsaw in Russian-occupied Poland, the young Marie Curie, originally named Maria Sklodowska, was a brilliant student, but she faced some challenging barriers. As a woman, she was barred from pursuing higher education, so in an act of defiance, Marie enrolled in the Floating University, a secret institution that provided clandestine education to Polish youth. By saving money and working as a governess and tutor, she eventually was able to move to Paris to study at the reputed Sorbonne. here, Marie earned both a physics and mathematics degree surviving largely on bread and tea, and sometimes fainting from near starvation.

In 1896, Henri Becquerel discovered that uranium spontaneously emitted a mysterious X-ray-like radiation that could interact with photographic film. Curie soon found that the element thorium emitted similar radiation. Most importantly, the strength of the radiation depended solely on the element’s quantity, and was not affected by physical or chemical changes. This led her to conclude that radiation was coming from something fundamental within the atoms of each element. The idea was radical and helped to disprove the long-standing model of atoms as indivisible objects. Next, by focusing on a super radioactive ore called pitchblende, the Curies realized that uranium alone couldn’t be creating all the radiation. So, were there other radioactive elements that might be responsible?

In 1898, they reported two new elements, polonium, named for Marie’s native Poland, and radium, the Latin word for ray. They also coined the term radioactivity along the way. By 1902, the Curies had extracted a tenth of a gram of pure radium chloride salt from several tons of pitchblende, an incredible feat at the time. Later that year, Pierre Curie and Henri Becquerel were nominated for the Nobel Prize in physics, but Marie was overlooked. Pierre took a stand in support of his wife’s well-earned recognition. And so both of the Curies and Becquerel shared the 1903 Nobel Prize, making Marie Curie the first female Nobel Laureate.

In 1911, she won yet another Nobel, this time in chemistry for her earlier discovery of radium and polonium, and her extraction and analysis of pure radium and its compounds. This made her the first, and to this date, only person to win Nobel Prizes in two different sciences. Professor Curie put her discoveries to work, changing the landscape of medical research and treatments. She opened mobile radiology units during World War I, and investigated radiation’s effects on tumors.

However, these benefits to humanity may have come at a high personal cost. Curie died in 1934 of a bone marrow disease, which many today think was caused by her radiation exposure. Marie Curie’s revolutionary research laid the groundwork for our understanding of physics and chemistry, blazing trails in oncology, technology, medicine, and nuclear physics, to name a few. For good or ill, her discoveries in radiation launched a new era, unearthing some of science’s greatest secrets.

From the TED-Ed Lesson The genius of Marie Curie - Shohini Ghose

Animation by Anna Nowakowska

A Brief Rest by PhotographyByHenrik

-

temporalschism reblogged this · 5 years ago

temporalschism reblogged this · 5 years ago -

thelatenightflowerhour liked this · 7 years ago

thelatenightflowerhour liked this · 7 years ago -

i-went-to-college liked this · 7 years ago

i-went-to-college liked this · 7 years ago -

greenotion liked this · 8 years ago

greenotion liked this · 8 years ago -

urb3aut1ful liked this · 8 years ago

urb3aut1ful liked this · 8 years ago -

screeching-rutabaga reblogged this · 8 years ago

screeching-rutabaga reblogged this · 8 years ago -

screeching-rutabaga liked this · 8 years ago

screeching-rutabaga liked this · 8 years ago -

scienceblogbyserena reblogged this · 8 years ago

scienceblogbyserena reblogged this · 8 years ago -

thereistroublethereischaos reblogged this · 8 years ago

thereistroublethereischaos reblogged this · 8 years ago -

thereistroublethereischaos liked this · 8 years ago

thereistroublethereischaos liked this · 8 years ago -

thepotatopuff liked this · 8 years ago

thepotatopuff liked this · 8 years ago -

dudells liked this · 8 years ago

dudells liked this · 8 years ago -

lucianoger reblogged this · 8 years ago

lucianoger reblogged this · 8 years ago -

lucianoger liked this · 8 years ago

lucianoger liked this · 8 years ago -

mazzymars liked this · 8 years ago

mazzymars liked this · 8 years ago -

risika77 reblogged this · 8 years ago

risika77 reblogged this · 8 years ago -

existxntixl liked this · 8 years ago

existxntixl liked this · 8 years ago -

6ft10 reblogged this · 8 years ago

6ft10 reblogged this · 8 years ago -

6ft10 liked this · 8 years ago

6ft10 liked this · 8 years ago -

life-on-lunar liked this · 8 years ago

life-on-lunar liked this · 8 years ago -

molo-moreno reblogged this · 8 years ago

molo-moreno reblogged this · 8 years ago -

digitalstylez liked this · 8 years ago

digitalstylez liked this · 8 years ago -

official-sopranino-sax-blog liked this · 8 years ago

official-sopranino-sax-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

s0ulfulminded reblogged this · 8 years ago

s0ulfulminded reblogged this · 8 years ago -

s0ulfulminded liked this · 8 years ago

s0ulfulminded liked this · 8 years ago -

noasaurus-blog liked this · 8 years ago

noasaurus-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

spadeskeletalspade liked this · 8 years ago

spadeskeletalspade liked this · 8 years ago -

mr-pi9 liked this · 8 years ago

mr-pi9 liked this · 8 years ago -

withfervor reblogged this · 8 years ago

withfervor reblogged this · 8 years ago -

australopeteicus liked this · 8 years ago

australopeteicus liked this · 8 years ago -

happykitty2408 liked this · 8 years ago

happykitty2408 liked this · 8 years ago -

mybrokencrown13 reblogged this · 8 years ago

mybrokencrown13 reblogged this · 8 years ago -

questionable-quirks-blog liked this · 8 years ago

questionable-quirks-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

dreamerarcher reblogged this · 8 years ago

dreamerarcher reblogged this · 8 years ago -

dreamerarcher liked this · 8 years ago

dreamerarcher liked this · 8 years ago -

nanobiot-topo-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago

nanobiot-topo-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago -

sandcrawl3r liked this · 8 years ago

sandcrawl3r liked this · 8 years ago -

basedassseal liked this · 8 years ago

basedassseal liked this · 8 years ago -

timallenphoto liked this · 8 years ago

timallenphoto liked this · 8 years ago -

theflyingquirrell-blog liked this · 8 years ago

theflyingquirrell-blog liked this · 8 years ago