What Is Gravitational Lensing?

What is Gravitational Lensing?

A gravitational lens is a distribution of matter (such as a cluster of galaxies) between a distant light source and an observer, that is capable of bending the light from the source as the light travels towards the observer. This effect is known as gravitational lensing, and the amount of bending is one of the predictions of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

This illustration shows how gravitational lensing works. The gravity of a large galaxy cluster is so strong, it bends, brightens and distorts the light of distant galaxies behind it. The scale has been greatly exaggerated; in reality, the distant galaxy is much further away and much smaller. Credit: NASA, ESA, L. Calcada

There are three classes of gravitational lensing:

1° Strong lensing: where there are easily visible distortions such as the formation of Einstein rings, arcs, and multiple images.

Einstein ring. credit: NASA/ESA&Hubble

2° Weak lensing: where the distortions of background sources are much smaller and can only be detected by analyzing large numbers of sources in a statistical way to find coherent distortions of only a few percent. The lensing shows up statistically as a preferred stretching of the background objects perpendicular to the direction to the centre of the lens. By measuring the shapes and orientations of large numbers of distant galaxies, their orientations can be averaged to measure the shear of the lensing field in any region. This, in turn, can be used to reconstruct the mass distribution in the area: in particular, the background distribution of dark matter can be reconstructed. Since galaxies are intrinsically elliptical and the weak gravitational lensing signal is small, a very large number of galaxies must be used in these surveys.

The effects of foreground galaxy cluster mass on background galaxy shapes. The upper left panel shows (projected onto the plane of the sky) the shapes of cluster members (in yellow) and background galaxies (in white), ignoring the effects of weak lensing. The lower right panel shows this same scenario, but includes the effects of lensing. The middle panel shows a 3-d representation of the positions of cluster and source galaxies, relative to the observer. Note that the background galaxies appear stretched tangentially around the cluster.

3° Microlensing: where no distortion in shape can be seen but the amount of light received from a background object changes in time. The lensing object may be stars in the Milky Way in one typical case, with the background source being stars in a remote galaxy, or, in another case, an even more distant quasar. The effect is small, such that (in the case of strong lensing) even a galaxy with a mass more than 100 billion times that of the Sun will produce multiple images separated by only a few arcseconds. Galaxy clusters can produce separations of several arcminutes. In both cases the galaxies and sources are quite distant, many hundreds of megaparsecs away from our Galaxy.

Gravitational lenses act equally on all kinds of electromagnetic radiation, not just visible light. Weak lensing effects are being studied for the cosmic microwave background as well as galaxy surveys. Strong lenses have been observed in radio and x-ray regimes as well. If a strong lens produces multiple images, there will be a relative time delay between two paths: that is, in one image the lensed object will be observed before the other image.

As an exoplanet passes in front of a more distant star, its gravity causes the trajectory of the starlight to bend, and in some cases results in a brief brightening of the background star as seen by a telescope. The artistic concept illustrates this effect. This phenomenon of gravitational microlensing enables scientists to search for exoplanets that are too distant and dark to detect any other way.Credits: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle

Explanation in terms of space–time curvature

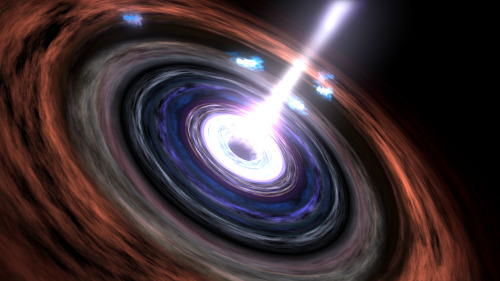

Simulated gravitational lensing by black hole by: Earther

In general relativity, light follows the curvature of spacetime, hence when light passes around a massive object, it is bent. This means that the light from an object on the other side will be bent towards an observer’s eye, just like an ordinary lens. In General Relativity the speed of light depends on the gravitational potential (aka the metric) and this bending can be viewed as a consequence of the light traveling along a gradient in light speed. Light rays are the boundary between the future, the spacelike, and the past regions. The gravitational attraction can be viewed as the motion of undisturbed objects in a background curved geometry or alternatively as the response of objects to a force in a flat geometry.

A galaxy perfectly aligned with a supernova (supernova PS1-10afx) acts as a cosmic magnifying glass, making it appear 100 billion times more dazzling than our Sun. Image credit: Anupreeta More/Kavli IPMU.

To learn more, click here.

More Posts from Donhq21 and Others

The future of the sun

In approximately 5-7 billion years, the sun will begin the helium-burning process, turning into a red giant star. When it expands, its outer layers will consume Mercury and Venus, and reach Earth. Scientists are still debating whether or not our planet will be engulfed, or whether it will orbit dangerously close to the dimmer star. Either way, life as we know it on Earth will cease to exist.

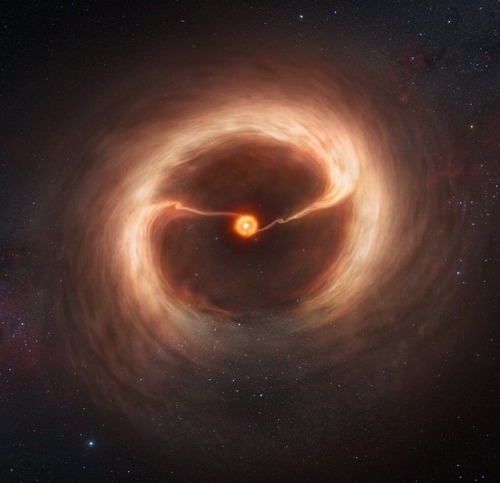

This artist’s impression shows the disc of gas and cosmic dust around the young star HD 142527. Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) telescope have seen vast streams of gas flowing across the gap in the disc. These are the first direct observations of these streams, which are expected to be created by giant planets guzzling gas as they grow, and which are a key stage in the birth of giant planets.

Credit: ESO / Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array

Sequence of Venus atmosphere images taken by the Venus Monitoring Camera (VMC) during the Venus Express orbit in July 2007. The view shows the southern hemisphere of the planet.

Credit: ESA/MPS/DLR/IDA

A zoomed-in picture of VY Canis Majoris, taken and processed from Rutherford Observatory telescope in 07 September 2014. If placed at the center of the Solar System, VY CMa’s surface would extend beyond the orbit of Jupiter, although there is still considerable variation in estimates of the radius, with some making it larger than the orbit of Saturn. (Rutherfurd Observatory/Columbia University)

NASA’s Fermi Satellite Celebrates 10 Years of Discoveries

On June 11, NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope celebrates a decade of using gamma rays, the highest-energy form of light in the cosmos, to study black holes, neutron stars, and other extreme cosmic objects and events.

Left: A STEREO B image of the far side of the sun during the Sept. 1, 2014, solar eruption. Right: The Earth-facing side of the sun at the same time as seen by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory. The view includes the area from which NASA’s Fermi detected high-energy gamma rays. Includes animated gif. Credit: NASA/STEREO and NASA/SDO

A rupture in the crust of a highly magnetized neutron star, shown here in an artist’s rendering, can trigger high-energy eruptions. Fermi observations of these blasts include information on how the star’s surface twists and vibrates, providing new insights into what lies beneath. Credits: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/S. Wiessinger

Fermi finds the first extragalactic gamma-ray pulsar. NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope has detected the first extragalactic gamma-ray pulsar, PSR J0540-6919, near the Tarantula Nebula (top center) star-forming region in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy that orbits our own Milky Way. Fermi detects a second pulsar (right) as well but not its pulses. PSR J0540-6919 now holds the record as the highest-luminosity gamma-ray pulsar. The angular distance between the pulsars corresponds to about half the apparent size of a full moon. Background: An image of the Tarantula Nebula and its surroundings in visible light. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center; background: ESO/R. Fosbury (ST-ECF)

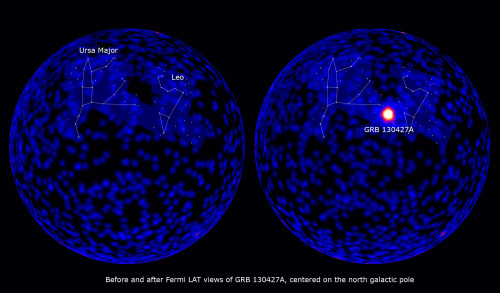

These maps, both centered on the north galactic pole, show how the sky looks at gamma-ray energies above 100 million electron volts (MeV). Left: The sky during a three-hour interval prior to the detection of GRB 130427A. Right: A three-hour interval starting 2.5 hours before the burst and ending 30 minutes into the event, illustrating its brightness relative to the rest of the gamma-ray sky. GRB 130427A was located in the constellation Leo near its border with Ursa Major, whose brightest stars form the familiar Big Dipper. For reference, this image includes the stars and outlines of both constellations. Labeled. Credit: NASA/DOE/Fermi LAT Collaboration.

Novae typically originate in binary systems containing sun-like stars, as shown in this artist’s rendering. A nova in a system like this likely produces gamma rays (magenta) through collisions among multiple shock waves in the rapidly expanding shell of debris. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/S. Wiessinger

Gamma Rays in Active Galactic Nuclei.

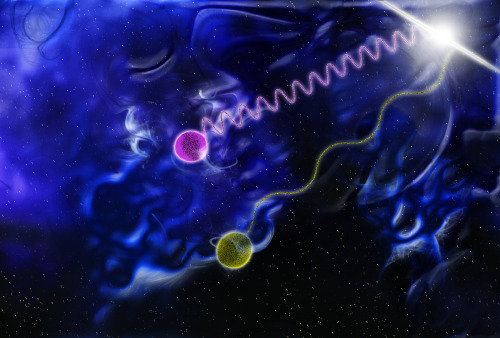

Gamma-ray Burst Photon Delay as Expected by Quantum Gravity. Print resolution still. In this illustration, one photon (purple) carries a million times the energy of another (yellow). Some theorists predict travel delays for higher-energy photons, which interact more strongly with the proposed frothy nature of space-time. Yet Fermi data on two photons from a gamma-ray burst fail to show this effect, eliminating some approaches to a new theory of gravity. Credit: NASA/Sonoma State University/Aurore Simonnet

“Fermi’s first 10 years have produced numerous scientific discoveries that have revolutionized our understanding of the gamma-ray universe,” said Paul Hertz, Astrophysics Division director at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

By scanning the sky every three hours, Fermi’s main instrument, the Large Area Telescope (LAT), has observed more than 5,000 individual gamma-ray sources, including an explosion called GRB 130427A, the most powerful gamma-ray burst scientists have detected.

In 1949, Enrico Fermi — an Italian-American pioneer in high-energy physics and Nobel laureate for whom the mission was named — suggested that cosmic rays, particles traveling at nearly the speed of light, could be propelled by supernova shock waves. In 2013, Fermi’s LAT used gamma rays to prove these stellar remnants are at least one source of the speedy particles.

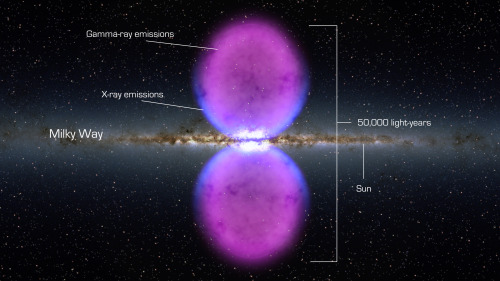

Fermi’s all-sky map, produced by the LAT, has revealed two massive structures extending above and below the plane of the Milky Way. These two “bubbles” span 50,000 light-years and were probably produced by the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy only a few million years ago.

read more

What are brown dwarfs?

In order to understand what is a brown dwarf, we need to understand the difference between a star and a planet. It is not easy to tell a star from a planet when you look up at the night sky with your eyes. However, the two kinds of objects look very different to an astronomer using a telescope or spectroscope. Planets shine by reflected light; stars shine by producing their own light. So what makes some objects shine by themselves and other objects only reflect the light of some other body? That is the important difference to understand – and it will allow us to understand brown dwarfs as well.

As a star forms from a cloud of contracting gas, the temperature in its center becomes so large that hydrogen begins to fuse into helium – releasing an enormous amount of energy which causes the star to begin shining under its own power. A planet forms from small particles of dust left over from the formation of a star. These particles collide and stick together. There is never enough temperature to cause particles to fuse and release energy. In other words, a planet is not hot enough or heavy enough to produce its own light.

Brown dwarfs are objects which have a size between that of a giant planet like Jupiter and that of a small star. In fact, most astronomers would classify any object with between 13 times the mass of Jupiter and 75 times the mass of Jupiter to be a brown dwarf. Given that range of masses, the object would not have been able to sustain the fusion of hydrogen like a regular star; thus, many scientists have dubbed brown dwarfs as “failed stars”.

A Trio of Brown Dwarfs

This artist’s conception illustrates what brown dwarfs of different types might look like to a hypothetical interstellar traveler who has flown a spaceship to each one. Brown dwarfs are like stars, but they aren’t massive enough to fuse atoms steadily and shine with starlight – as our sun does so well.

On the left is an L dwarf, in the middle is a T dwarf, and on the right is a Y dwarf. The objects are progressively cooler in atmospheric temperatures as you move from left to right. Y dwarfs are the newest and coldest class of brown dwarfs and were discovered by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE. WISE was able to detect these Y dwarfs for the first time because it surveyed the entire sky deeply at the infrared wavelengths at which these bodies emit most of their light. The L dwarf is seen as a dim red orb to the eye. The T dwarf is even fainter and appears with a darker reddish, or magenta, hue. The Y dwarf is dimmer still. Because astronomers have not yet detected Y dwarfs at the visible wavelengths we see with our eyes, the choice of a purple hue is done mainly for artistic reasons. The Y dwarf is also illustrated as reflecting a faint amount of visible starlight from interstellar space.

In this rendering, the traveler’s spaceship is the same distance from each object. This illustrates an unusual property of brown dwarfs – that they all have the same dimensions, roughly the size of the planet Jupiter, regardless of their mass. This mass disparity can be as large as fifteen times or more when comparing an L to a Y dwarf, despite the fact that both objects have the same radius. The three brown dwarfs also have very different atmospheric temperatures. A typical L dwarf has a temperature of 2,600 degrees Fahrenheit (1,400 degrees Celsius). A typical T dwarf has a temperature of 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit (900 degrees Celsius). The coldest Y dwarf so far identified by WISE has a temperature of less than about 80 degrees Fahrenheit (25 degrees Celsius).

Sources: starchild.gsfc.nasa.gov & nasa.gov

image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

What are Quarks?

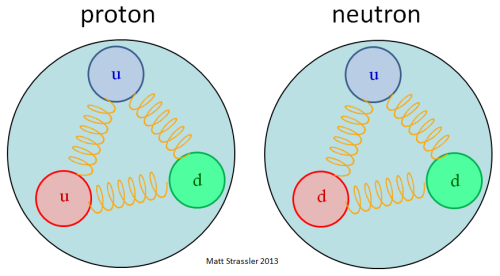

A quark is a type of elementary particle and a fundamental constituent of matter. Quarks combine to form composite particles called hadrons, the most stable of which are protons and neutrons, the components of atomic nuclei.

There are six types of quarks, known as flavors: up, down, strange, charm, top, and bottom Up and down quarks have the lowest masses of all quarks. The heavier quarks rapidly change into up and down quarks through a process of particle decay: the transformation from a higher mass state to a lower mass state. Because of this, up and down quarks are generally stable and the most common in the universe, whereas strange, charm, bottom, and top quarks can only be produced in high energy collisions (such as those involving cosmic rays and in particle accelerators).

Due to a phenomenon known as color confinement, quarks are never directly observed or found in isolation; they can be found only within hadrons, such as baryons (of which protons and neutrons are examples) and mesons. For this reason, much of what is known about quarks has been drawn from observations of the hadrons themselves.

This movie illustrates the action inside the nucleus of a deuterium atom containing a proton and a neutron, each with three quarks. An electron strikes a quark inside a proton, passing energy to the quark before the electron bounces back. The quark now has so much energy “stuffed” into it, it creates a cascade of new particles as it flies out of the proton. The result is two new, two-quark particles.

Quarks have various intrinsic properties, including electric charge, mass, color charge, and spin. Quarks are the only elementary particles in the Standard Model of particle physics to experience all four fundamental interactions, also known as fundamental forces (electromagnetism, gravitation, strong interaction, and weak interaction), as well as the only known particles whose electric charges are not integer multiples of the elementary charge.

An animation of the interaction inside a neutron. The gluons are represented as circles with the color charge in the center and the anti-color charge on the outside.

Mass

Current quark masses for all six flavors in comparison, as balls of proportional volumes. Proton and electron (red) are shown in bottom left corner for scale.

Two terms are used in referring to a quark’s mass: current quark mass refers to the mass of a quark by itself, while constituent quark massrefers to the current quark mass plus the mass of the gluon particle field surrounding the quark. These masses typically have very different values. Most of a hadron’s mass comes from the gluons that bind the constituent quarks together, rather than from the quarks themselves.

Field lines from color charges

In quantum chromodynamics, a quark’s color can take one of three values or charges, red, green, and blue. An antiquark can take one of three anticolors, called antired, antigreen, and antiblue (represented as cyan, magenta and yellow, respectively). Gluons are mixtures of two colors, such as red and antigreen, which constitutes their color charge. QCD considers eight gluons of the possible nine color–anticolor combinations to be unique.

Spin

In quantum mechanics and particle physics, spin is an intrinsic form of angular momentum carried by elementary particles, composite particles (hadrons), and atomic nuclei.

Spin is one of two types of angular momentum in quantum mechanics, the other being orbital angular momentum. The orbital angular momentum operator is the quantum-mechanical counterpart to the classical angular momentum of orbital revolution: it arises when a particle executes a rotating or twisting trajectory (such as when an electron orbits a nucleus)

Gluon

A gluon is an elementary particle that acts as the exchange particle (or gauge boson) for the strong force between quarks. It is analogous to the exchange of photons in the electromagnetic force between two charged particles. In layman’s terms, they “glue” quarks together, forming protons and neutrons.

Baryons and Mesons

A baryon is a composite subatomic particle made up of three quarks. Baryons and mesons belong to the hadron family of particles, which are the quark-based particles. As quark-based particles, baryons participate in the strong interaction, whereas leptons, which are not quark-based, do not.

In particle physics, mesons are hadronic subatomic particles composed of one quark and one antiquark, bound together by the strong interaction. Because mesons are composed of quark sub-particles, they have a physical size, with a diameter of roughly one femtometer, which is about 2⁄3 the size of a proton or neutron. All mesons are unstable, with the longest-lived lasting for only a few hundredths of a microsecond. Charged mesons decay (sometimes through mediating particles) to form electronsand neutrinos. Uncharged mesons may decay to photons. Both of these decays imply that color is no longer a property of the byproducts.

Source: wikipedia, hyperphysics

(To know more click the links: Baryon, Meson, Gluon)

Images: x, x, x, x, x

Transient by Dustin Farrell

Sauce in 4K: vimeo.com/245581179

Solar System

Outbursts of a newborn star in the orion constellation

Credit: ESO/M. McCaughrean

-

thisworldisntrealhoney liked this · 1 year ago

thisworldisntrealhoney liked this · 1 year ago -

lovepalecollectorpeachme liked this · 1 year ago

lovepalecollectorpeachme liked this · 1 year ago -

sleepy-soft-boi reblogged this · 2 years ago

sleepy-soft-boi reblogged this · 2 years ago -

happilykrispygalaxypensieri liked this · 2 years ago

happilykrispygalaxypensieri liked this · 2 years ago -

starfaringships reblogged this · 2 years ago

starfaringships reblogged this · 2 years ago -

spockvarietyhour liked this · 2 years ago

spockvarietyhour liked this · 2 years ago -

darkcomicsbookslibrariesthing liked this · 2 years ago

darkcomicsbookslibrariesthing liked this · 2 years ago -

polenasty liked this · 2 years ago

polenasty liked this · 2 years ago -

alxsparks liked this · 2 years ago

alxsparks liked this · 2 years ago -

werewolfin liked this · 2 years ago

werewolfin liked this · 2 years ago -

utsuro-bune-0 reblogged this · 2 years ago

utsuro-bune-0 reblogged this · 2 years ago -

utsuro-bune-0 liked this · 2 years ago

utsuro-bune-0 liked this · 2 years ago -

playwith reblogged this · 2 years ago

playwith reblogged this · 2 years ago -

nosemeocurreunnombrexd2570534vc liked this · 2 years ago

nosemeocurreunnombrexd2570534vc liked this · 2 years ago -

colordesigns reblogged this · 2 years ago

colordesigns reblogged this · 2 years ago -

stretch-en-wallz liked this · 2 years ago

stretch-en-wallz liked this · 2 years ago -

stefanopreto reblogged this · 2 years ago

stefanopreto reblogged this · 2 years ago -

stefanopreto liked this · 2 years ago

stefanopreto liked this · 2 years ago -

cronostitan liked this · 2 years ago

cronostitan liked this · 2 years ago -

chiprupt liked this · 2 years ago

chiprupt liked this · 2 years ago -

flowersandspacestuff liked this · 2 years ago

flowersandspacestuff liked this · 2 years ago -

ilokilok liked this · 2 years ago

ilokilok liked this · 2 years ago -

stevenmiami liked this · 2 years ago

stevenmiami liked this · 2 years ago -

stoicdaddypants reblogged this · 2 years ago

stoicdaddypants reblogged this · 2 years ago -

autumnemrys reblogged this · 2 years ago

autumnemrys reblogged this · 2 years ago -

autumnemrys liked this · 2 years ago

autumnemrys liked this · 2 years ago -

kaze-no-tsubasa reblogged this · 2 years ago

kaze-no-tsubasa reblogged this · 2 years ago -

lenbryant reblogged this · 2 years ago

lenbryant reblogged this · 2 years ago -

thisperspective reblogged this · 2 years ago

thisperspective reblogged this · 2 years ago -

lenbryant liked this · 2 years ago

lenbryant liked this · 2 years ago -

readwing liked this · 2 years ago

readwing liked this · 2 years ago -

silentexplorer liked this · 2 years ago

silentexplorer liked this · 2 years ago -

tachvintlogic reblogged this · 2 years ago

tachvintlogic reblogged this · 2 years ago -

kaiannanthi reblogged this · 2 years ago

kaiannanthi reblogged this · 2 years ago -

kaiannanthi liked this · 2 years ago

kaiannanthi liked this · 2 years ago -

carloshgc-char reblogged this · 2 years ago

carloshgc-char reblogged this · 2 years ago -

sixtydaychips liked this · 2 years ago

sixtydaychips liked this · 2 years ago