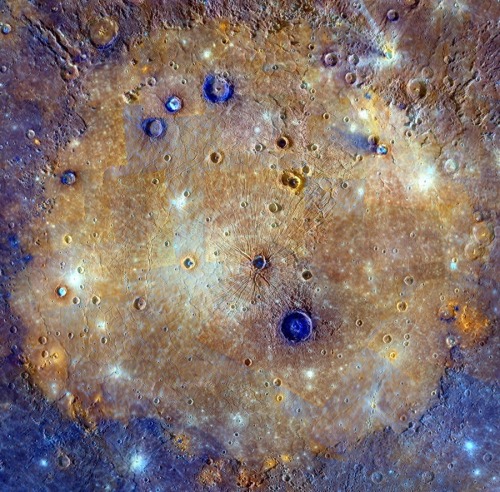

The Sprawling Caloris Basin On Mercury Is One Of The Solar System’s Largest Impact Basins, Created

The sprawling Caloris basin on Mercury is one of the solar system’s largest impact basins, created during the early history of the solar system by the impact of a large asteroid-sized body. The multi-featured, fractured basin spans about 1,500 kilometers in this enhanced color mosaic based on image data from the Mercury-orbiting MESSENGER spacecraft. Mercury’s youngest large impact basin, Caloris was subsequently filled in by lavas that appear orange in the mosaic. Craters made after the flooding have excavated material from beneath the surface lavas. Seen as contrasting blue hues, they likely offer a glimpse of the original basin floor material. Analysis of these craters suggests the thickness of the covering volcanic lava to be 2.5-3.5 kilometers. Orange splotches around the basin’s perimeter are thought to be volcanic vents.

Image Credit: NASA, Johns Hopkins Univ. APL, Arizona State U., CIW

More Posts from Astrotidbits-blog and Others

Comet McNaught.

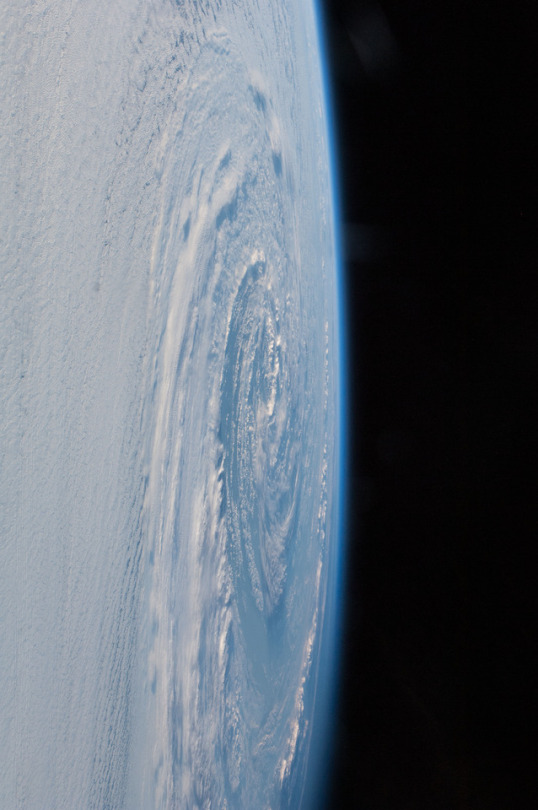

Pre-Winter Storm, Southwestern Australia in 2014

Credit: NASA / ISS

China’s giant alien-hunting telescope is ready

Our alien-hunting game just got a lot stronger with the completion of a huge radio telescope in the Guizhou province of China. It’s called the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST), and it’s designed to listen for signs of alien life out in the cosmos. The telescope is finished, but the construction was not without human rights controversy.

Follow @the-future-now

The Handle 2 camera, another doomed Kodak instant, 1979.

1959 Radio Man

Aerospace Engineering Magazine April 1962

FLAIR FLIGHT A contrast-enhanced image produced from the Hubble images of comet ISON taken April 23, 2013 reveals the subtle structure in the inner coma of the comet; the coma decreases in brightness proportionally to the distance from the nucleus. Comet ISON, thought to have travelled from the Oort Cloud surrounding our solar system beginning a million years ago, will make its closest approach to the Sun on Thursday. (Photo: NASA via AP / The Telegraph)

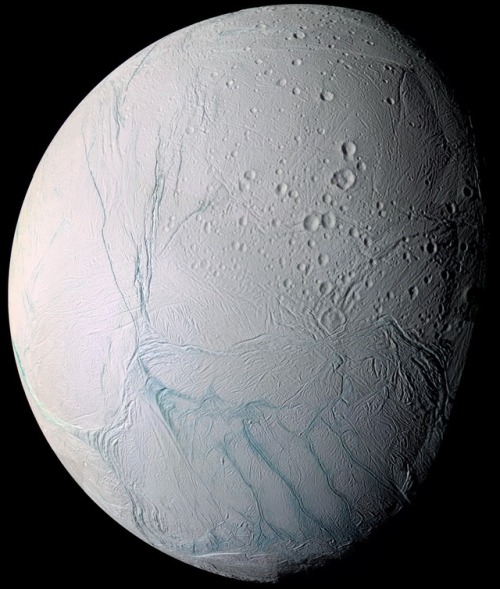

Enceladus - Life in our solar system?

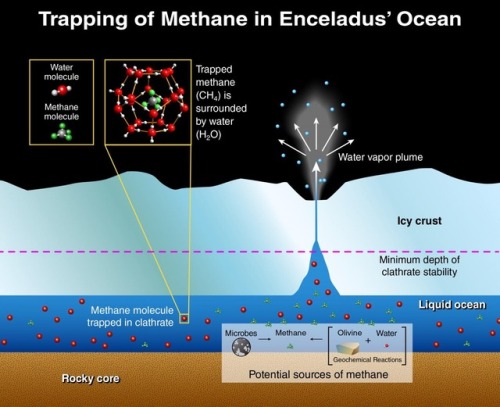

Enceladus is Saturns icy moon that measures approximately 504km in diameter, about a tenth of the size of Saturn’s largest moon Titan. Almost completely covered in ice, this moon could potentially harbour the same type of life-sustaining chemical reactions found in deep sea hydrothermal vents here on Earth.

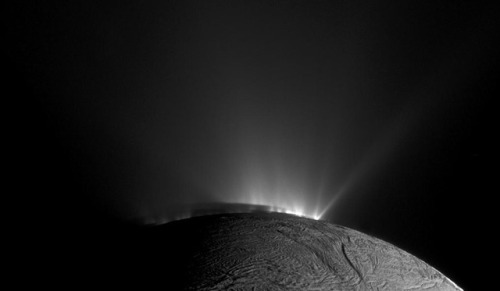

In 2005, NASA’s Saturn orbiting Cassini spacecraft spotted geysers of water and ice erupting fro fissures near Enceladus’ South Pole. Scientists believe they originate from a great ocean beneath the shell of ice. This ocean manages to stay liquid because the gravitational force exerted by Saturn is so intense that it twists and stretches the moon generating internal heat.

In October 2015, Cassini went on a dive through one of the plumes passing within just 39km of Enceladus’ surface. A team of scientists led by Hunter Waite analysed the observations made by the spacecraft. They discovered that the geysers contain between 0.4%-1.4% molecular hydrogen (H2) and 0.3%-0.8% carbon dioxide (CO2). These are being produced continuously by reactions between hot water and rock near the core of the moon. Some of the most primitive metabolic pathways found in microbes at deep ocean hydrothermal vents involve the reduction of CO2 with H2 to form methane (CH4) by a process known as methanogenesis.

-

agreatcircle liked this · 6 years ago

agreatcircle liked this · 6 years ago -

ksyu1 reblogged this · 7 years ago

ksyu1 reblogged this · 7 years ago -

universumnow reblogged this · 8 years ago

universumnow reblogged this · 8 years ago -

astrotidbits-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago

astrotidbits-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago -

astrotidbits-blog liked this · 8 years ago

astrotidbits-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

dicarpri0 reblogged this · 8 years ago

dicarpri0 reblogged this · 8 years ago -

so-this-is-my-blog-i-guess liked this · 8 years ago

so-this-is-my-blog-i-guess liked this · 8 years ago -

getthekit reblogged this · 8 years ago

getthekit reblogged this · 8 years ago -

workman liked this · 8 years ago

workman liked this · 8 years ago -

spinningininfinity liked this · 8 years ago

spinningininfinity liked this · 8 years ago -

redcloud liked this · 8 years ago

redcloud liked this · 8 years ago -

so-this-is-my-blog-i-guess reblogged this · 8 years ago

so-this-is-my-blog-i-guess reblogged this · 8 years ago -

bluevixen07 reblogged this · 9 years ago

bluevixen07 reblogged this · 9 years ago -

bluevixen07 liked this · 9 years ago

bluevixen07 liked this · 9 years ago -

bovodammit-blog liked this · 9 years ago

bovodammit-blog liked this · 9 years ago -

fogandbranches reblogged this · 9 years ago

fogandbranches reblogged this · 9 years ago -

galaxygirl-jack liked this · 9 years ago

galaxygirl-jack liked this · 9 years ago -

karolytomaa-blog liked this · 9 years ago

karolytomaa-blog liked this · 9 years ago -

made-of-stars-28 liked this · 9 years ago

made-of-stars-28 liked this · 9 years ago -

diamondsforlife liked this · 9 years ago

diamondsforlife liked this · 9 years ago -

youobviouslyloveowls reblogged this · 9 years ago

youobviouslyloveowls reblogged this · 9 years ago -

aqgayrius reblogged this · 9 years ago

aqgayrius reblogged this · 9 years ago -

nospacenocaps liked this · 9 years ago

nospacenocaps liked this · 9 years ago -

cabult reblogged this · 9 years ago

cabult reblogged this · 9 years ago -

cabult liked this · 9 years ago

cabult liked this · 9 years ago -

rebornnightmare liked this · 9 years ago

rebornnightmare liked this · 9 years ago -

golittlerecordgo reblogged this · 9 years ago

golittlerecordgo reblogged this · 9 years ago -

blondeaf reblogged this · 9 years ago

blondeaf reblogged this · 9 years ago -

cybertimetravelblizzard liked this · 9 years ago

cybertimetravelblizzard liked this · 9 years ago -

another-zero reblogged this · 9 years ago

another-zero reblogged this · 9 years ago -

zadachojojishi liked this · 9 years ago

zadachojojishi liked this · 9 years ago -

turtletommy liked this · 9 years ago

turtletommy liked this · 9 years ago -

euphoric-faces liked this · 9 years ago

euphoric-faces liked this · 9 years ago -

einesnachts reblogged this · 9 years ago

einesnachts reblogged this · 9 years ago